Introduction

Canada’s 2025 federal election delivered a painful result for the New Democratic Party. Entering the campaign with 24 seats, the NDP ultimately won just 7 and lost Official Party status in the House of Commons for the first time since 1993. What accounts for this outcome and could it have been avoided? How does it compare to other electoral ebbs throughout the party’s history? What are the NDP’s prospects, and to what extent does the 2025 result risk consolidating a US-style duopoly between Conservative and Liberal parties for Canadian federal politics in the longer term? With these and other related questions in mind, this essay will offer a broad assessment of the 2025 federal election and its aftermath, and several more general observations about the NDP. As the party conducts its leadership race and debates the path forward, my modest aim for this assessment is to engage some of the key issues and questions raised by the 2025 NDP campaign, beginning with a broad survey of the election itself.

Assessing the 2025 Campaign

The 2025 federal election was, in many ways, one shaped by extraordinary developments and singular conditions: an unexpected continental trade war, open threats of annexation from a US president, the sudden exit of an unpopular Prime Minister, and his replacement by a former central banker. Any reasonable assessment of the NDP campaign itself should thus begin by acknowledging the exceptional circumstances in which it took place – circumstances the party and its leadership could neither have predicted nor done anything to control.

The previous fall, most strategists and observers expected a campaign fought along the related axes of Prime Minister Justin Trudeau’s unpopularity and the soaring cost of living. Despite sagging approval ratings and mounting pressure from within his own caucus, towards the end of 2024 Trudeau looked determined to lead the Liberals in the next election and was poised to be an ideal foil for both the NDP and the Conservatives.

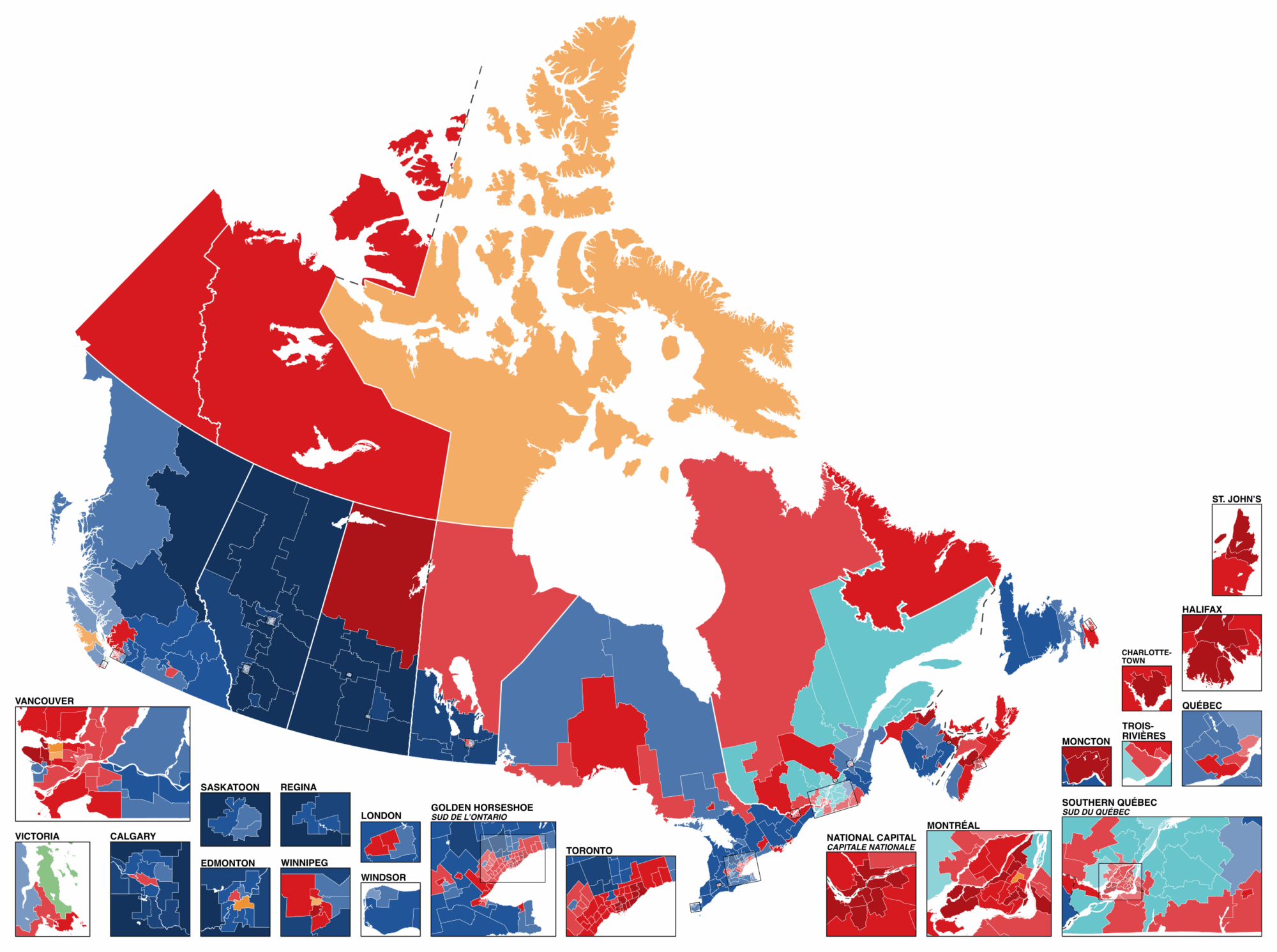

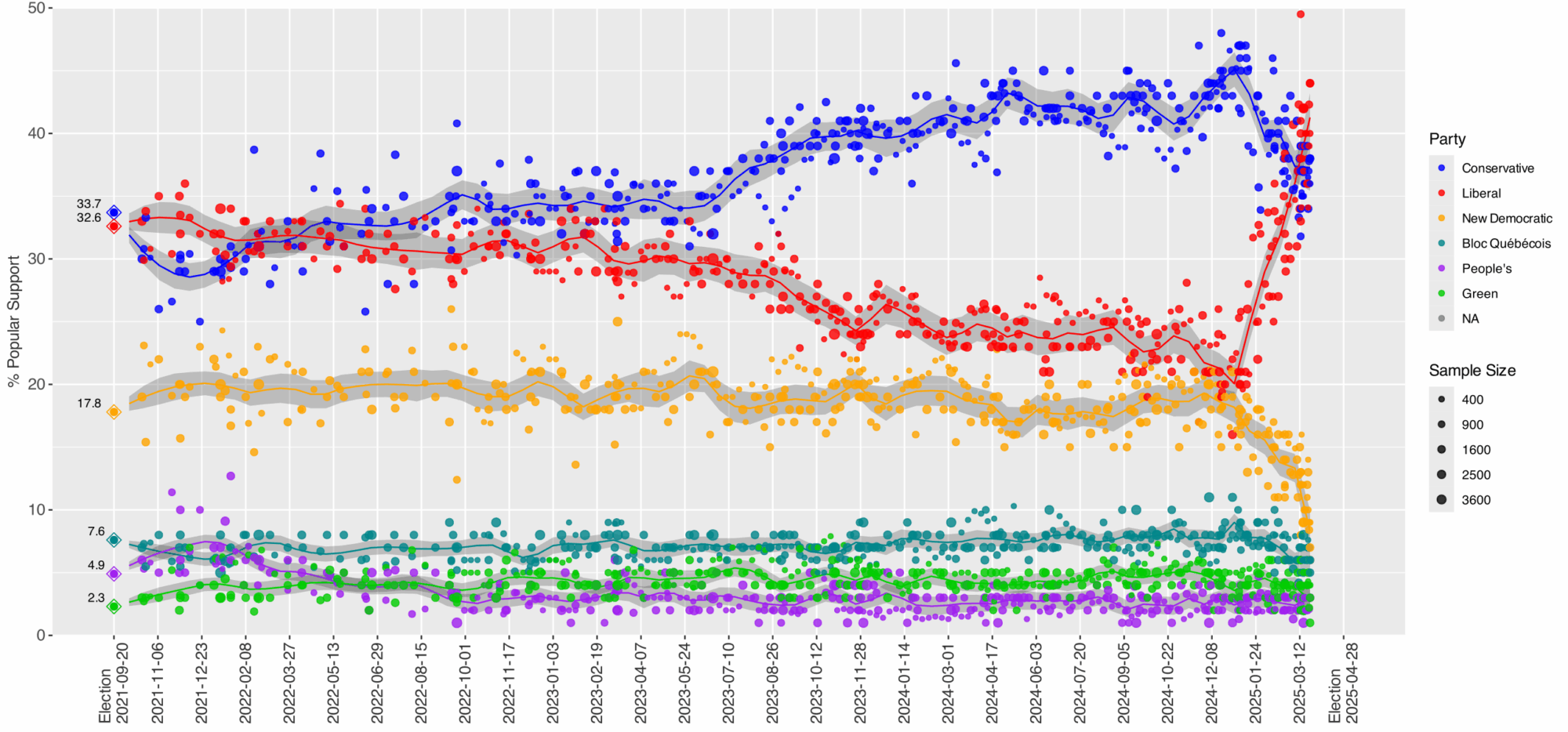

Instead, a whirlwind of events quickly upended the political dynamic and produced a more volatile electoral landscape; a fact attested by frenzied swings in polling that saw the Liberals recover, the Tories’ commanding lead evaporate, and the NDP slide from its competitive position in the high teens to single digits in a matter of weeks following Donald Trump’s second presidential inauguration in January 2025.

Here, the psychological impact on the electorate of Trump’s trade war and 51st state rhetoric was considerable. In moments of national emergency or times of war, political scientists have observed that the resulting rally ‘round the flag effect often redounds to the benefit of incumbent governments. Trump’s victory and its aftermath seem to have had exactly that effect. In turn, an election once destined to be a referendum on the record of an unpopular Liberal government abruptly became a very different beast. Had Trudeau remained, it’s doubtful the Liberals could have recovered to the same extent. But, thanks to his replacement by the managerial Mark Carney as leader of the Liberal Party by March 2025, they were exceptionally well positioned to exploit the new dynamic.

These unique circumstances pose some obvious challenges for any postmortem. If the campaign, after all, was one defined by novel conditions that will never be repeated, to what extent can wider lessons be drawn? When it comes to the NDP’s performance during the writ period itself, I am mostly content to leave any detailed autopsy of individual campaign maneuvers to others. Nonetheless, the party clearly waited longer than it should have before pivoting to the rejigged narrative it adopted in the election’s final weeks, dropping its leader’s ‘I’m running for prime minister’ messaging less than a month ahead of election day.

Having planned to run a leader-centric campaign framed as a two-way race between Jagmeet Singh and Conservative Party leader Pierre Poilievre, it was visibly slow to change course (a charge that might also be levelled at the Conservatives). The transition from “we’re running to win” to “elect more New Democrats” in the final weeks was never going to be easy. But, had the party adapted more quickly to the new dynamic, before the campaign period, it is possible more of the electoral fallout could have been contained.

Under different circumstances, and with the Trump factor removed, the NDP’s original strategy would likely have fared better and delivered more seats. Among other things, its platform included several ambitious policies aimed at addressing the cost-of-living crisis (notably a cap on grocery prices and a program of national rent control) and Singh proved quite effective in the election’s two debates. Absent the Trump factor, or faced with Trudeau instead of Carney, both would undoubtedly have found a warmer reception from Canadian voters.

Much has since been made of Tory victories in former NDP strongholds like Windsor West and London Fanshawe, and the supposed loss of working-class support for the NDP to the Conservatives. But despite periodic media discourse to the contrary, the decisive factor in the NDP’s collapse — evident in these seats and many others — was its considerable bleeding of support to the Liberals. To this point, data published by Ipsos Reid suggests that, while five percent of 2021 NDP voters switched to the Conservatives, nearly four times that number (19 percent) switched to the Liberals. Even in seats that swung to the former, this often had major implications.

Relatedly, it is worth considering whether the NDP’s 2022 Parliamentary Confidence and Supply Agreement with the Trudeau government played a role in the subsequent migration of votes to other parties, particularly the Liberals. Some eight months before the election (and before the termination of the Agreement in September 2024), David Moscrop speculated that the important policy gains contained in the deal – among them a pharmacare framework, expanded dental coverage, and anti-scab legislation – might not translate into electoral gains for its junior partner. Since the election, other commentators have advanced a stronger version of this case: variously suggesting that the NDP’s deal with the Liberals blurred public perceptions of its distinctiveness, unhelpfully associated it with the unpopular Trudeau and diminishing the credibility of its opposition to the government. In this spirit, the University of Saskatchewan’s David McGrane argues that the deal “turbocharged” the strategic voting phenomenon that has dogged the NDP in the past:

Singh’s criticism of the Liberals during the recent election campaign rang hollow given that he had held to the agreement for 2.5 years before backing out. That implicitly gave NDP supporters permission to vote Liberal. Voters’ thinking may have been that the Liberals could not be that scary if the NDP had supported them.

Whether one fully accepts this line of reasoning or not, the Confidence and Supply Agreement clearly did not pay the electoral dividends some NDP strategists hoped it would.

Looking back and looking forward

In electoral terms, there can be no sugarcoating of the NDP’s 2025 result. By any metric, whether seat count or popular vote, it represents the single worst outcome for parliamentary social democracy since the founding of the Co-Operative Commonwealth Federation (CCF) in 1932. Placed in wider historical perspective, however, it may also reflect one part of a cycle that is all too familiar.

Throughout its now 93-year history, the fortunes of the CCF-NDP have perennially ebbed and flowed in quite dramatic fashion. During the first decade of its existence, the party never broke 10 percent in the popular vote, winning just 8 seats in 1940. Three years later, it led in national polls and had formed the Official Opposition in Canada’s largest province after the 1943 Ontario election. With Tommy Douglas’ landslide 1944 victory in Saskatchewan, it seemed only a matter of time before the CCF formed a national government. But even as events elsewhere — notably the UK Labour Party’s victory in Britain’s 1945 general election — reinforced the impression of social democracy’s favourable electoral prospects in Canada, the CCF’s gains were minimal. After peaking in 1945 with 28 seats and 15.6 percent of the popular vote, the CCF gradually declined to the point of near collapse during the Conservative John Diefenbaker landslide of the 1958 election — which saw even heavyweight MPs like leader MJ Coldwell and Stanley Knowles personally defeated. The personal popularity of Diefenbaker on the Prairies, the ideological flexibility of the Liberals, the growing anti-socialist climate of the Cold War, and the rising importance of nationalism within the Quebec labour movement steadily combined to roll back the CCF’s gains.

Since these early days, the same pattern has periodically repeated itself. By the mid-1970s, an era of growing pains and sometimes contentious internal NDP debates gave way to a new high watermark. For the first time the NDP came to power in British Columbia in 1972, and elsewhere won back elections in the prairie socialist heartlands of Manitoba and Saskatchewan. In Ontario, the NDP under Stephen Lewis returned to Official Opposition in Ontario after the 1975 election for the first time since the CCF breakthrough three decades earlier. Throughout the next 14 years during Ed Broadbent’s federal leadership, provincial fortunes oscillated while the NDP crept ever closer to the long elusive goal of national power, ranking first in several polls and, for the first time in its history, leading in the province of Quebec.

In 1988, however, the strategic dilemma posed by the Mulroney’s government’s free trade agreement yet again thwarted the party’s quest for government. Between the deal’s relative popularity in Quebec and the Liberal capture of the anti-free trade vote in Ontario, the NDP found itself squeezed by all-too familiar pressures even as it achieved a record 43-seat showing. With 1988 having yielded neither triumph nor disaster, both came soon enough. On the heels of an unexpected majority victory in Ontario’s 1990 provincial election, the 1993 federal campaign saw the federal NDP lose 35 of its (then record) 44 seats, and its vote share plummet from 20.38 percent to just 6.88 percent. Between the growing unpopularity of the Rae government, the emergence of the Reform Party in the West, and the increasingly conservative bent of global politics in the 1990s, its prospects suddenly looked bleak.

The still elusive goal of winning federal power notwithstanding, the CCF-NDP has persisted across the decades because social democracy has continued to hold profound appeal among millions of Canadians.

Viewed against this backdrop, recent history has in many ways been a retread of quite familiar ground: from the gradual rebuilding of the Alexa McDonough and Jack Layton eras spanning the late 1990s and early 2000s through the historic breakthrough of 2011, the disappointment of 2015, and the sectional decline the federal NDP has suffered ever since. This century, the electoral peaks and troughs have been notably more pronounced and come more quickly than their earlier equivalents. To wit: in the roughly ten years spanning the summer of 2015 (the start of that year’s election campaign) to the present, the party has boasted both its highest ever and lowest ever seat counts in Parliament.

From this rather sobering observation, however, it may be possible to draw a somewhat more hopeful conclusion. The still elusive goal of winning federal power notwithstanding, the CCF-NDP has persisted across the decades because social democracy has continued to hold profound appeal among millions of Canadians. Four decades of neoliberalism have not fundamentally altered that reality, and the 21st century’s increasingly fluid political and electoral landscape may yet redound to the NDP’s benefit. With all this mind, there is no reason to think the party’s current predicament will be a permanent one. The overwhelming weight of historical precedent suggests the NDP will both survive and rebound from its present low of 7 seats. The question is not, fundamentally, whether the party will recover, but rather what the nature and path to that recovery will look like.

Here, both the NDP’s history and its more recent experience offer important lessons. If the party hopes to rebuild on a national scale with the goal of eventually forming government, it will need to solve the strategic issues that have persistently thwarted even its most promising efforts to date. Broadly-speaking, these include (in no particular order): 1) the continued salience of the federalist/sovereigntist dynamic in Quebec and the obvious challenges this poses for a national social democratic party; 2) the continued, if sometimes provisional loyalty of many self-identified progressives and so-called “strategic voters” to the Liberals; 3) the party’s periodic inability to translate its often high levels of provincial support in Ontario and the West into a commensurate number of federal seats. All of these, no doubt, merit dedicated pieces of their own and each should be approached with openness and humility.

In any case, it’s clear the NDP cannot effectively recover if its renewal is treated solely as a rebranding exercise. Breaking the logjam of two-party politics will require more than just effective leadership and good messaging. Fundamentally, it calls for a creative populist strategy as well: rooted in both the engaged participation of a mass membership and the kind of bold, left-wing program that is impossible for the Liberals to appropriate or co-opt.

If nothing else, the current political landscape would seem to offer fertile ground for just such an approach. Having won a mandate on the promise of “nation-building,” the Liberal Party is now in the process of implementing what is arguably the most comprehensive austerity program Canada has seen in decades. Across the world, the neoliberal model retains only minimal democratic legitimacy and has resoundingly failed to achieve the vision of inclusive prosperity its proponents continue to tout. Having been declared moribund, meanwhile, democratic socialism has returned as a real, if still fledgling presence in global politics.

In important ways, there has not been a stronger case for breaking with the political and economic status quo since the CCF was founded in the early 1930s. Renewing and rebuilding its successor clearly demands no less than the same spirit of radical ambition.