On July 15th, 2023, Québec Premier François Legault took to social media to praise Kevin Lambert’s novel, Que notre joie demure (translated in English as May Our Joy Endure the following year). The novel, Legault wrote, addresses “the difficulty of debates in our society” and offers a “nuanced critique of the Quebec bourgeoisie.” In a scathing comment left below the Premier’s post, Lambert fired back: “you have to read with your eyes closed not to see how the portrait of the city that is depicted in the novel goes against the destructive, anti-poor, anti-immigrant, pro-property and pro-rich policies of your government.” The public quarrel quickly became a media event and sales of the novel nearly doubled in the days following.

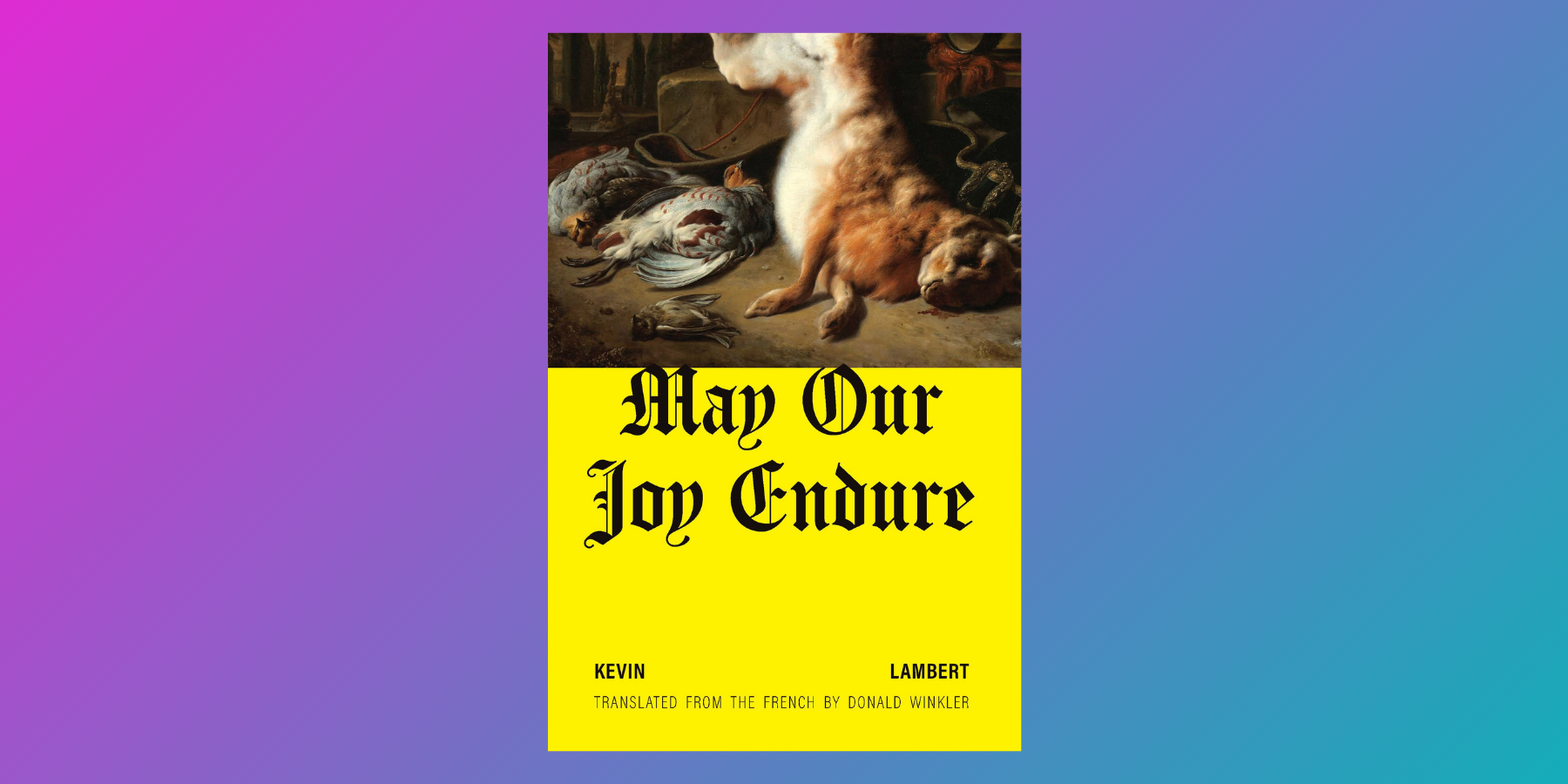

Readers of Lambert’s work should not have been surprised by this heated exchange. Since the publication of his debut in 2017, the 32-year old writer from Saguenay has established himself as an unsparing critic of the social, political, and economic conditions of contemporary Québec. His first two novels—You Will Love What You Have Killed and Querelle of Roberval—abounded in sex and violence as though engineered to offend just about everyone. Instead, they won praise and prizes in both Québec and France. Upon its publication in 2022, Que notre joie demure was longlisted for the esteemed Prix Goncourt and won the Prix Médici, placing Lambert in the company of figures such as Marie-Claire Blais and Dany Leferrière. Biblioasis Press and translator Donald Winkler have endeavoured to replicate Lambert’s success with English-language readers; May Our Joy Endure appeared in translation in September 2024.

The novel follows renowned architect Céline Wachowski as she nears her 70th birthday. From humble and troubled beginnings in the Montréal-suburb of Roxboro, Céline has climbed her way to global stardom. Lambert details his protagonist’s accomplishments at length: Céline’s firm, Ateliers C/W, has built “houses of influential personalities,” including those of Paul McCartney, Julianne Moore, Madonna, and Françoise Bettencourt, and has designed major works around the world, including “three legendary buildings, the famous Decco Tower in New York, the media centre for the London Olympics, and the Abu Dhabi Guggenheim Museum that had just opened its door.”

More than just an architect, Céline is a public figure and financial mogul: her lifestyle show Old House, New House is a hit on Netflix; she is close friends with celebrities like “Sigourney,” “Meryl,” and “Julianne”; she was the subject of a Harper’s Bazaar profile written by Joan Didion. Her extensive investment portfolio has done well, with Forbes estimating her net worth at a cool $7.2 billion. On the personal level, Céline’s “magnetism that calls to mind that of the great British actresses” bewitches all those who are lucky to find themselves in her presence.

Despite Céline’s global stature, she has felt insufficiently honoured in her home province. That is, until a multinational Amazon-like corporation called WeBuy decides to build a new headquarters in Montréal on the condition that Céline design the building. A site is selected in the Mile-Ex neighbourhood—an actually-existing plot of land beside the Université de Montréal’s MIL Campus to the north of Mont Royal—and Céline is struck with inspiration for the building’s design in a cup of tea.

Lambert’s placing the fictional WeBuy Complex in a real location is a key to the commentary on gentrification and urban inequality at the centre of the novel. In an academic article from 2019, Mary Sprague and Norma Rantisi note that the City of Montreal has played an active role in transforming the formerly-industrial Mile-Ex into a hub for “knowledge and service-oriented businesses and new residential development.” Or, as Lambert writes, “Mile-Ex … had already undergone a serious transformation, largely due to the installation there of artificial-intelligence, video games, and state of the art-of-the-art-tech companies.” Throughout the novel, Lambert demonstrates a keen understanding of urban development theory. His framing of the WeBuy Complex seems to model what geographer David Harvey has coined “urban entrepreneurialism,” in which local governments go to great lengths to attract international investment. Indeed, Lambert writes that “WeBuy had settled on Montreal because of the fiscal advantage and generous investments pledged by all levels of government.”

As the novel progresses, both the WeBuy Complex and Céline are beset by controversy. Protestors flock to the building site and march in opposition to the gentrification that will result from the project. Meanwhile, Céline is the subject of a damning two-part New Yorker profile, which exposes her dubious financial dealings and abusive behavior towards employees. Lambert cleverly uses the profile as a didactic implement to explain the workings of gentrification and elsewhere documents the lives of those who have been displaced in the process.

In the fallout from the New Yorker piece, Céline is forced off the board of the firm she founded. She retreats to her mansion along the Rivière des Prairies and tries to find meaning in the work of Proust. As in Todd Hayne’s film Tàr, we witness an autopsy of a life after the social death of cancellation and follow our character’s quest for redemption.

Despite the force of its critique, May Your Joy Endure is by no means a screed. Lambert’s talents as a prose stylist are evident even in translation. His sentences possess an incantatory quality—the opening sentence runs nearly a page—and the reader is never far from a jarring image or metaphor, as when Céline’s voice is described as breaking “the silence with the solicitude and patience of a nurse lancing an abscess.” Lambert writes about architecture with a meticulousness that duly renders the beauty of his character’s creations. The narrative also benefits from the polyvocality of a chorus of characters, including Pierre-Moïse, Celine’s overshadowed second-in-command, and Gabriela, a fledgling architect who bears the brunt of her boss’s ire. By examining this diverse cast of characters in all their complexities—and hypocrisies—Lambert has offered a model for writing across differences of age, gender, race and class with sensitivity and compassion.

May Our Joy Endure is a timely cultural intervention. Between 2023 and 2024 monthly rents for a 1-bedroom apartment in Montréal jumped over 10%—in Lambert’s words “an affordable dwelling place had become rarer than a winter without rain”—and a 2024 survey conducted by Vivre en Ville in partnership with the City of Montreal found that 15% of respondents reported that they have experienced homelessness, a 50% increase from a year prior. In 2023, Premier Legault’s Coalition Avenir Québec passed Bill 31, allowing landlords to reject lease transfers, a mechanism which had previously helped moderate rent prices. It bears mentioning that the current Minister of Housing, France-Elaine Duranceau, is a former real estate agent and property flipper who was found to have violated ethics regulations after she fast-tracked a meeting with a lobbyist who also happened to be a longtime friend and partner in real estate projects. Lambert’s condemnation of this state of affairs is evident in both his novel and his exchange with the Premier.

Late in the novel, Lambert stages a debate over the role of fiction in the balance of power. Michel—Céline’s nationalist and xenophobic personal assistant—proclaims “that there is a seed of domination inscribed in literature itself … Racine, Molière, Shakespeare, the list is long, they all wrote their masterpieces to buttress and entertain the ruling class, works made to order affirming their patrons’ moral ascendancy over the people.” One could just as easily provide a list of counter-example—from Orwell to Ursula K. Le Guin—of writers who have spoken truth to power and envisioned a more egalitarian world. In our own moment, Lambert has made one such contribution. It’s an encouraging sign that people in positions of power are reading his work; we can only hope that they read a little more carefully.