Since the late 2000s, Canada’s economic slowdown has been debated in terms of technological fatigue, demographic trends, monetary constraints, and global trade headwinds. This paper contends that the underlying source of stagnation fundamentally points to distributional imbalances and structural demand deficiency. Today’s stagnation is not cyclical, but a symptom of a structural trap—a regime of distributional stagnation rooted in the failure of the neoliberal paradigm to reconcile economic growth with social equity.

This analysis situates Canada’s stagnation within broader debates on “secular stagnation” and macroeconomic paradigm choice, drawing on leading theories that emphasize the role of demand, inequality, and institutional decline. There are three structural channels through which income inequality drives stagnation: (1) reduced household consumption due to top-heavy income distribution; (2) erosion of labour power weakening wage growth and demand; (3) a disconnect between rising profits and falling productive investment.

Tracing the evolution of Canada’s macroeconomic paradigm from postwar Keynesianism to neoliberalism informs this discussion on how the latter has transformed the structure of inequality and undermined demand-driven growth. A fundamental shift in economic governance centered on structural equity and broad-based participation is essential. Escaping the trap requires a structural shift toward “inclusive growth”: rebuilding labour’s bargaining power, restoring the wage–productivity link, and redirecting investment toward long-term public productive goals. Canada’s economic performance and the viability of a social contract grounded in equity and resilience is at stake without this paradigm shift.

The Paradigmatic Structure of Inequality

Redistributive policy touches on one of the core questions in modern society: how should members of society live together under a social contract grounded in mutual obligation, especially when the rewards of economic growth and the burdens of downturns are not automatically shared equitably. It raises essential questions about how societies allocate the gains of growth and the cost of contraction. At the heart of modern governance, this is not just a technical or economic concern but normative choices embedded in institutional frameworks, which reflect competing visions of justice, the role of the state, and the purpose of public policy. These systems reveal deeper beliefs about the nature of the market (whether it is self-correcting or structurally unjust?), the trade-off between efficiency and equity, and the political philosophy behind them—whether public institutions should focus on maximizing individual liberty or advancing collective wellbeing.

In modern capitalist economies, economic growth does not necessarily lead to inclusive prosperity. The distributive outcomes of growth are profoundly shaped by the macroeconomic paradigms that guide public policy. These paradigms frame how governments define and pursue the goals of growth, stability, and distribution—and in doing so, they have shaped the evolution of income inequality. Since the mid-20th century, Canada’s political economy has been primarily dominated by two paradigms: the Keynesian consensus and neoliberalism. The former aimed to deliver broad-based growth with stable social structure through public intervention and full employment policies. The latter, by contrast, prioritized efficiency, market liberalization, and fiscal restraint, gradually eroding labour’s share in the distribution of income.

Economic paradigms are not neutral technical constructs. They are institutional expressions of underlying power relations, shaping the rules of the game in favour of some groups over others. Each paradigm encodes assumptions about what constitutes a healthy economy, what role the state should play, and how economic rewards should be allocated. When a prevailing paradigm generates problems it cannot solve—such as stagflation under Keynesianism or inequality and stagnation under neoliberalism—it loses legitimacy, giving rise to crisis, political instability, and ultimately, the search for a new paradigm.

The COVID-19 pandemic exposed the structural failures of the neoliberal model—marked by wage stagnation, weakened labour protections, and rising inequality. Built on market efficiency and fiscal restraint, neoliberalism has failed to deliver broad-based prosperity and now faces a crisis of legitimacy: the outcomes it delivers (high inequality and low growth) stand in stark contrast to its original promises of prosperity through efficiency. Much like the fall of Keynesianism in the 1970s, its promises have unraveled under economic inertia and structural imbalance. Canada stands at a crossroads: persist with an exhausted paradigm or adopt a new framework that addresses inequality and sustains long-term growth.

The Keynesian Paradigm and the Era of Stable Inequality

From the postwar era until the late 1970s, Canada and most other advanced economies operated within the Keynesian macroeconomic and social policy framework. The central tenet of this paradigm was clear: full employment was essential for balanced growth and social stability. Through active fiscal policy, counter-cyclical public spending, and the expansion of welfare state programs, governments ensured that economic growth was broadly shared. Inequality existed, but it remained stable because income growth was roughly proportionate across the income distribution.

Importantly, this consensus emerged from a historical moment. The architects of the Keynesian state had witnessed the mass unemployment of the Great Depression and the mobilization of the war economy. They were deeply skeptical of the ability of markets to self-regulate, and they saw government intervention as essential to stabilizing demand and promoting equitable growth. As a result, growth and equality became mutually reinforcing elements of the postwar economic order. This period reflected an implicit social contract: capital enjoyed growing markets and profits, while labour benefited from rising wages, job security, and a stronger social safety net. (Osberg, 2021) The tax and transfer system of this Keynesian era played a central role in moderating inequality in Canada.

The Neoliberal Paradigm and the Rise of Unequal Growth

By the late 1970s, the Keynesian framework came under strain in Canada and in capitalist countries around the world that had adopted this paradigm. Stagflation, fiscal deficits, and global capital mobility challenged the foundations of the postwar model. In its place, neoliberalism emerged as a new global economic paradigm, prioritizing inflation control, budget balance, deregulation, and the primacy of market forces. Government was no longer viewed as the engine of growth or redistribution, but as a rules-setting entity whose role was to ensure the smooth operation of competitive markets.

This paradigmatic shift in capitalist framework since the 1970s has had profound effects on Canada’s political economy:

- Erosion of worker bargaining power: Union density declined steadily, especially in the private sector. Increased minimum wages could not compensate for the loss of collective bargaining coverage.

- Regressive tax and social policy reforms: The structure of taxation and public spending was reshaped to favour high-income households, weakening the redistributive impact of the state.

- Stagnant middle incomes: Real median wage growth stalled, even as GDP and corporate profits rose. Income gains were increasingly captured by the top 1%.

- Financialization and declining public investment: Profit-seeking shifted from productive investment to financial markets. Public sector retrenchment and privatization further weakened the capacity of the state to guide economic development.

The new regime had a profound effect by increasing inequality. Unlike the postwar period, where inequality was stable, the neoliberal era normalized its increase. Disparities in income and wealth became structural features of the economy, not temporary deviations. This paradigm, far from delivering inclusive prosperity, entrenched a system in which growth was no longer shared.

This shift in paradigm laid the groundwork for Canada’s current macroeconomic malaise: a stagnating middle class, underinvestment, precarious labour markets, and a polarized distribution of income. Understanding the evolution and limits of these paradigms is essential for charting a new path forward.

Revisiting Secular Stagnation

Advanced capitalist economies, including Canada, are facing long-term structural headwinds that are slowing trend growth and depressing the neutral interest rate, or r* (the level at which monetary policy neither stimulates nor restrains the economy). In Canada, demographic aging, weak productivity gains, rising precautionary savings, and lower returns on investment have reduced economic potential. Businesses typically invest less in an environment where expected returns are uncertain or diminished, and trade tensions reinforce this hesitation, leading to an economy characterized by excess saving relative to productive investment demand. (Eggertsson and Mehrotra, 2014) Canada’s structural economic issues have only intensified with the instigation of the US Trump Administration’s trade conflict beginning in early 2025.

Demographic trends and slower productivity growth are lowering long-term growth prospects, contributing to a lower r*. It limits central banks’ ability to stimulate the economy through interest rate cuts during downturns. Economist Lawrence Summers and others describe this condition as “secular stagnation”—a state in which the economy “is not capable of achieving satisfactory growth and stable financial conditions simultaneously” and “the achievement of sufficient demand to bring about full employment” has become problematic at low interest rates (Summers, 2014). Orthodox economists identify supply-side constraints—such as diminishing returns to innovation and demographic shifts (Gordon, 2016)—or chronic demand shortfall—exacerbated by the interest rate zero lower bound (ZLB), economic hysteresis influenced by path dependency, and declining investment—as symptomatic of secular stagnation which then limits the effectiveness of monetary policy. (Summers, 2014)

The debate on secular stagnation emerged during the 2008 Global Financial Crisis and the subsequent decade-long stagnation period, which exposed structural limits to monetary policy effectiveness at the ZLB. The neoliberal monetary policy framework—particularly dominant in capitalist economies from the 1990s to 2008—prioritized low and stable inflation as the mandate of central banks, while downplaying other goals like full employment or equitable income distribution. After a decade of stagnant growth in the aftermath of the 2008 Crisis, the COVID-19 pandemic reinforced these vulnerabilities, pushing advanced economies into a de facto liquidity trap. Prior to 2008, the ZLB was unheard of in mainstream economic and policy debates, based on the assumption that interest rate adjustments alone could effectively manage the business cycle and the idea of a lower bound, or even negative r*, was unthinkable. The crisis shattered this orthodoxy, revealing the dangers of overreliance on interest rates, resistance to countercyclical fiscal policy, and disregard for the role of income and wealth distribution that shape aggregate demand.

Canada’s present economic conditions may not meet the full definition of secular stagnation, but it is not immune–signs of structural stagnation are evident. Despite avoiding full-blown deflation or a ZLB monetary trap like the Eurozone or Japan have experienced in recent decades in response to economic crises, Canada faces persistent demand weakness, underinvestment, fragile consumption, and diminishing marginal returns. These factors reduce the effectiveness of neoliberal paradigm policy tools. The decline in r* in Canada and around the world has reduced monetary policy effectiveness, placing structural pressure on long-run growth and macroeconomic resilience, and narrowed available policy space. High household debt-fueled consumption is unsustainable, while prolonged weakness in non-residential investment reflects insufficient demand expectations and weak capital formation. The Canadian labour market appears strong, yet is increasingly characterized by low-wage, temporary, and non-standard employment. While a ZLB or a negative r* has not yet been triggered as current rates remain above neutral and some policy room has been regained by the recent cycle as of 2025, Canada could approach the ZLB more rapidly were a future downturn to occur.

Canada’s experience reflects impacts shaped by a moderate form of neoliberalism that became the country’s paradigmatic economic framework beginning during the tenure of Prime Minister Brian Mulroney and continuing into the Jean Chretien era of the 1990s. While the country retains elements of a social welfare state—such as public healthcare and education—that are indicative of Keynesian economic policies, Canada’s economic trajectory has been shaped by liberalizing reforms since the 1980s. The new paradigm of the time encouraged trade liberalization (e.g., NAFTA), privatization, fiscal austerity, and market-oriented labour policies across the Canadian economy. In the decades since this paradigm shift, the tax system has become less progressive, and social spending has been relatively constrained. Although Canada’s financial system weathered the 2008 Crisis better than that of the United States or European Union, the underlying structural imbalances deepened.

These dynamics point to a deeper structural pathology: persistent demand suppression rooted in income and wealth inequality. Understanding this pathology requires shifting focus from the mechanics of monetary policy toward analysis of the distributional foundations of macroeconomic stagnation.

The Deeper Issue: How Income Inequality Locks the Economy into Secular Stagnation

Beneath Canada’s economic stagnation lies a deeper issue: how rising income inequality suppresses effective demand. In Canada, income inequality has become a central driver of stagnation, dampening consumption, weakening aggregate demand, and disincentivizing productive investment. It has reshaped the economy’s distributional structure, affecting household behaviour, corporate strategy, and labour market outcomes. These dynamics have been reinforced by decades of policy choices rooted in the neoliberal paradigm, leaving Canada trapped in a stagnation equilibrium, rooted in long-standing structural imbalances of policy, institutions, and market power.

An examination of the demand side in three parts contributes to a full understanding of how inequality locks Canada’s economy into stagnation. First, the weakening of household consumption—influenced by wage stagnation and weakened purchasing power as well as debt dependency in housing and consumption—has led to the erosion of aggregate demand. Second, turning to the labour market, the erosion of worker bargaining power and declining union coverage has had implications for wage dynamics and labour’s share of income. Lastly, on the firm side of the equation there has been a growing profit–investment disconnect that can be traced from the effects of distributional imbalances through to their impact on capital formation. To break free from this stagnation trap, structural reforms addressing income redistribution and inclusive growth are essential.

1. Demand Weakness: Inequality and Financialization

Income Inequality and Wage Stagnation

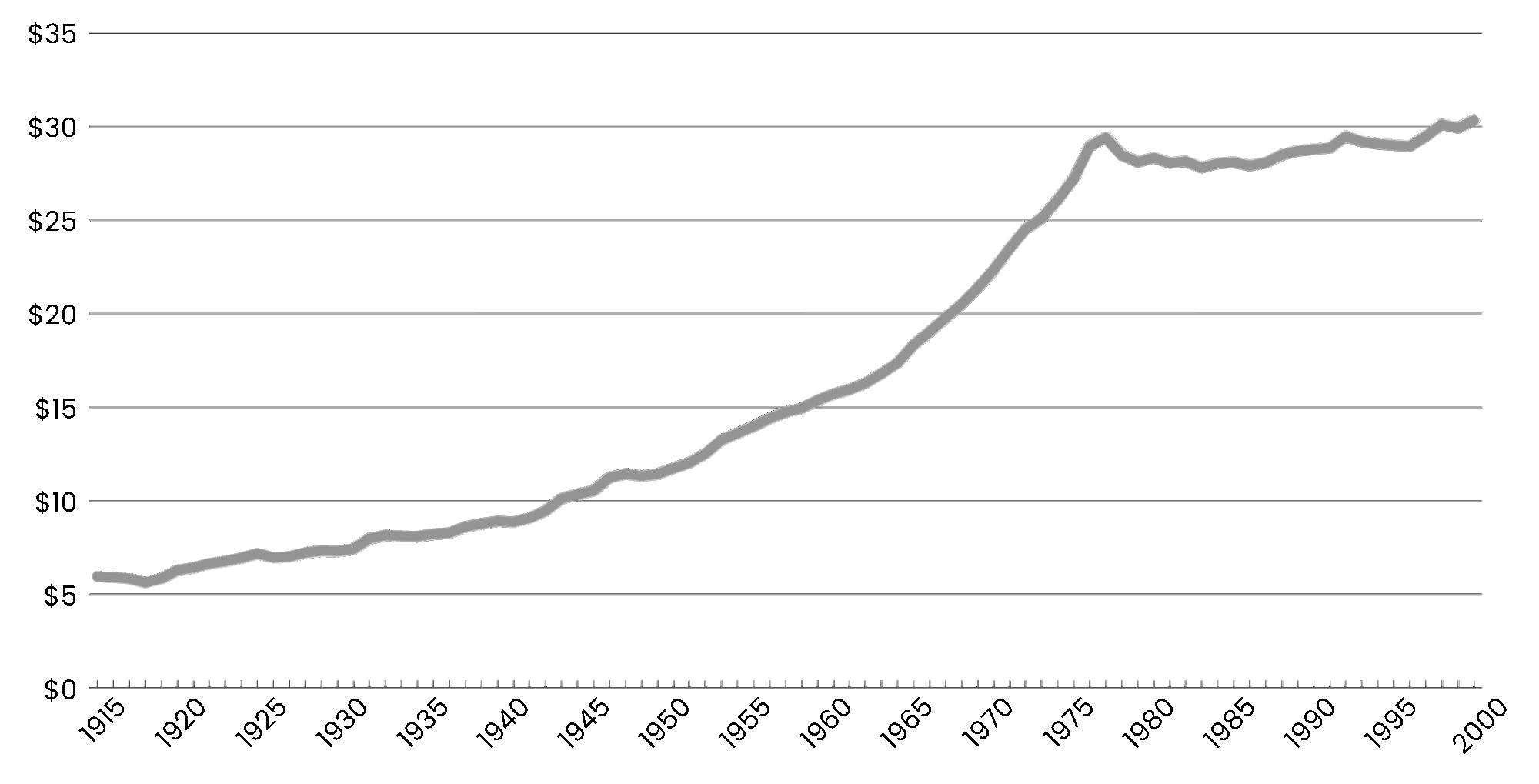

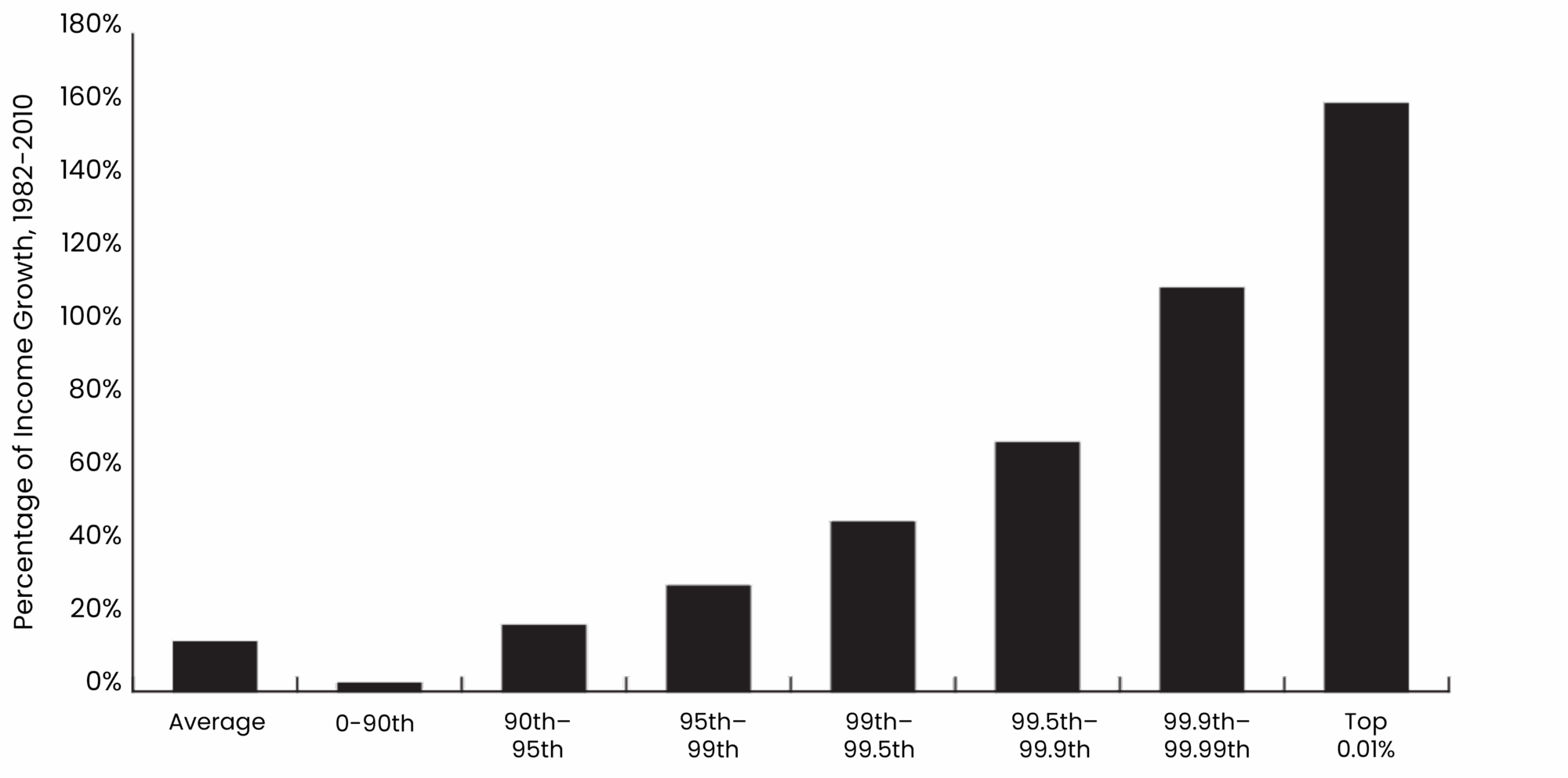

Income inequality is the primary driver of weak aggregate demand. Since the 1980s, income inequality has intensified in Canada. Real wages for the middle class have largely stagnated (Figure 1) since the turn of the century, while the income share of the top 1 percent has steadily increased (Figure 2). Nearly all income growth from 1982 to 2010 was accrued to the top income fractiles, particularly the top 0.01%. This extreme concentration of growth is consistent across peer countries like the US and Australia who have also experienced similar policy paradigms. In contrast, income gains for the bottom 90 percent were negligible. This stark polarization underscores the extent of structural inequality and the failure of growth to benefit the broad population.

Figure 1 – Real Average Hourly Wage (2019$), Canada, 1914-2000

Source: Lars Osberg, ‘From Keynesian Consensus to Neo-Liberalism to the Green New Deal 75 years of income inequality in Canada,’ Canadian Centre for Policy Alternatives (March 2021); CANSIM ii V I603501; Urquhart et al “Historical Statistics of Canada.”

Figure 2 – Total Income Growth by Fractile, Canada, 1982-2010

Source: Inequality: The Canadian Story, Report, eds. David A. Green, W. Craig Riddell, and France St-Hilaire, Institute for Research on Public Policy, February 2017; calculations by authors based on F. Alvaredo, T. Atkinson, T. Piketty and E. Saez; based on market income, which includes all income except government transfers and capital gains—data based on all taxfilers, including those with zero income.

This upward distribution has direct macroeconomic consequences. As income shifts toward high earners with a lower marginal propensity to consume, household consumption weakens, thereby weakening aggregate demand. This is evident in the Canadian context: despite elevated corporate profits and modest productivity gains, real wages for most workers have failed to keep pace. Instead, gains have accumulated in dividends, retained earnings, and asset appreciation. This decoupling of wage and productivity growth leads to stagnation in workers’ incomes, having broken the income-consumption channel. High-income earners who save more, spend less, and invest in financial assets, contribute less to overall consumption. As a result, household consumption has become increasingly fragile and dependent on debt and asset inflation rather than wage income.

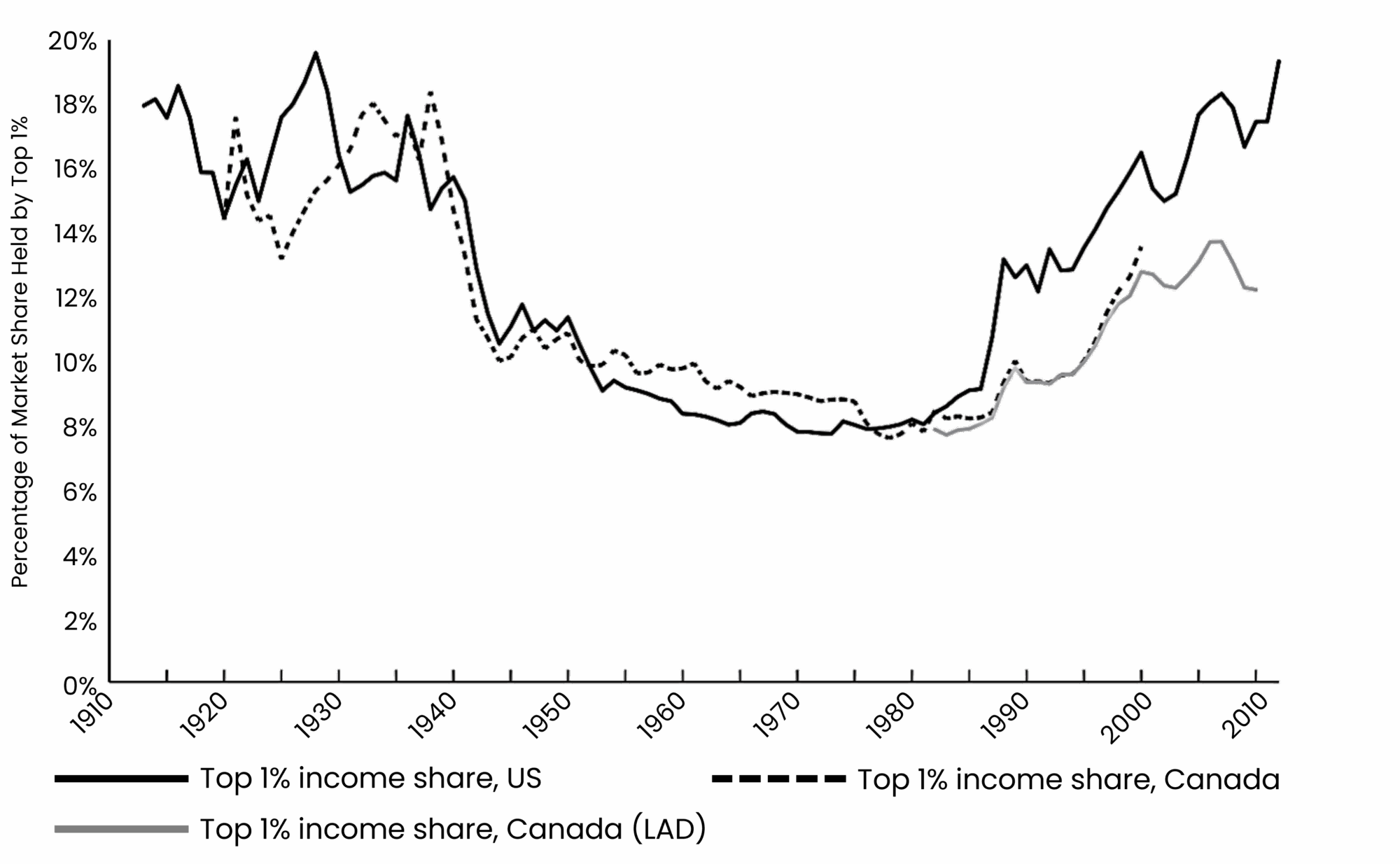

Figure 3 illustrates a U-shaped trend in top income concentration. After declining under mid-century Keynesian policies, the share of market income held by the top 1 percent has surged since the 1980s. The US has nearly returned to Gilded Age levels of income inequality; Canada, though slower, follows a similar path reflecting the neoliberal policy shift. In Canada, progressive taxes and income-tested transfers, provincial surtaxes on high earners, and labour-market institutions such as collective bargaining have acted as institutional buffers, partially restraining—but not reversing—the rise in extreme polarization.

Figure 3 – Share of Market Income Held by the Top 1 Percent of Earners, Canada and the United States, 1913-2012

Source: Inequality: The Canadian Story, Report, eds. David A. Green, W. Craig Riddell, and France St-Hilaire, Institute for Research on Public Policy, February 2017; calculations by authors based on F. Alvaredo, T. Atkinson, T. Piketty and E. Saez; LAD = Longitudinal Administrative Databank.

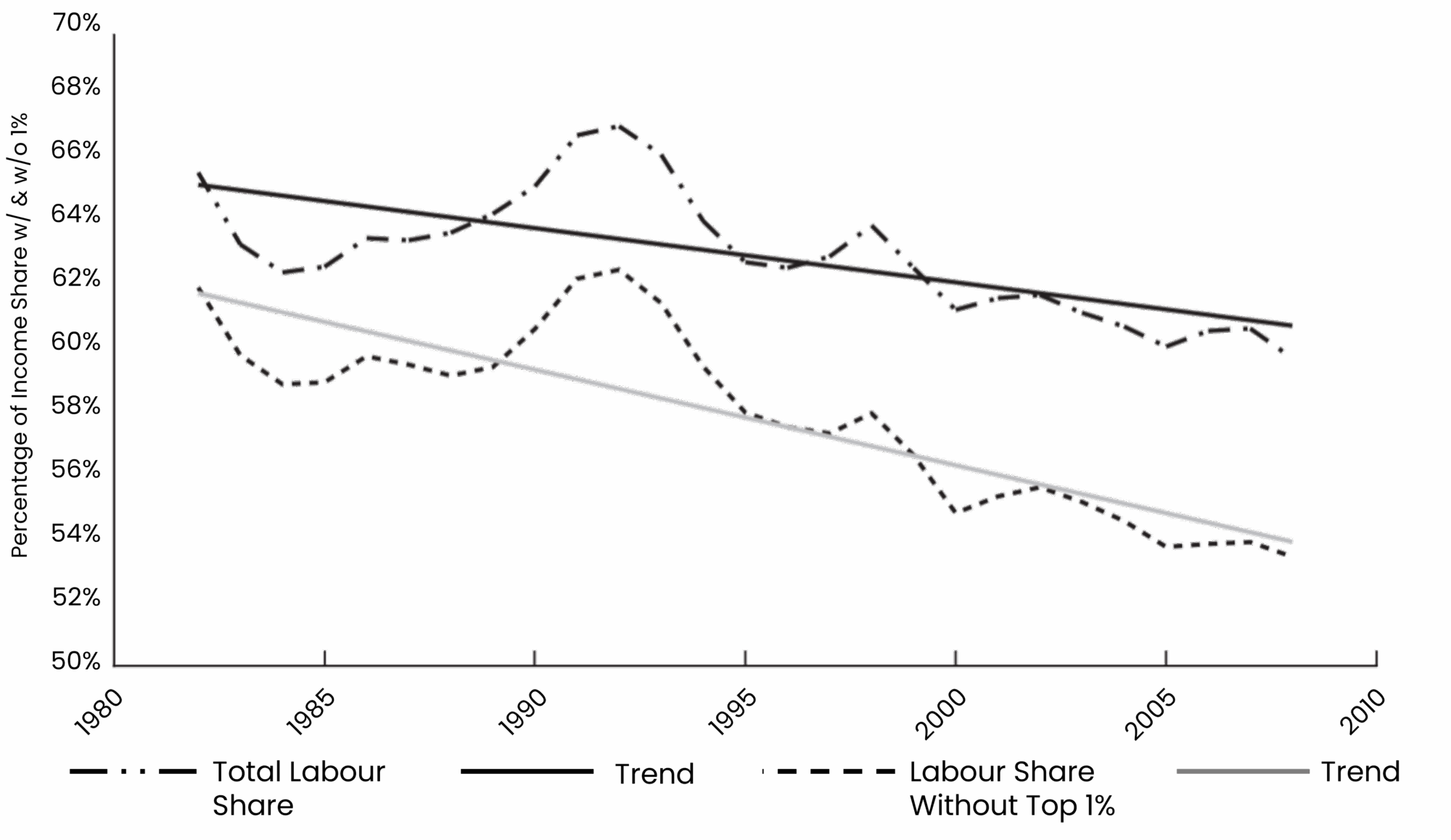

Figure 4 illustrates the masking effect of income concentration: excluding the incomes of the top 1 percent from the data reveals a significantly steeper decline in the labour share of total income. While the overall labour share appears relatively stable when the richest are included, the income share accruing to the broad workforce has fallen more sharply. This decoupling is a classic illustration of “growth without inclusion” (Rammelt 2021), whereby GDP may expand, yet gains are increasingly concentrated at the top, while labour income for middle- and lower-income households erodes, undermining consumption resilience and reinforcing chronic demand shortfalls.

Figure 4 – Labour Share of Total Income With and Without the Top 1 Percent of Earners, Canada, 1982-2008

Source: Inequality: The Canadian Story, Report, eds. David A. Green, W. Craig Riddell, and France St-Hilaire, Institute for Research on Public Policy, February 2017; calculations by authors based on Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development, OECD Data, Productivity Unit Labour Costs.

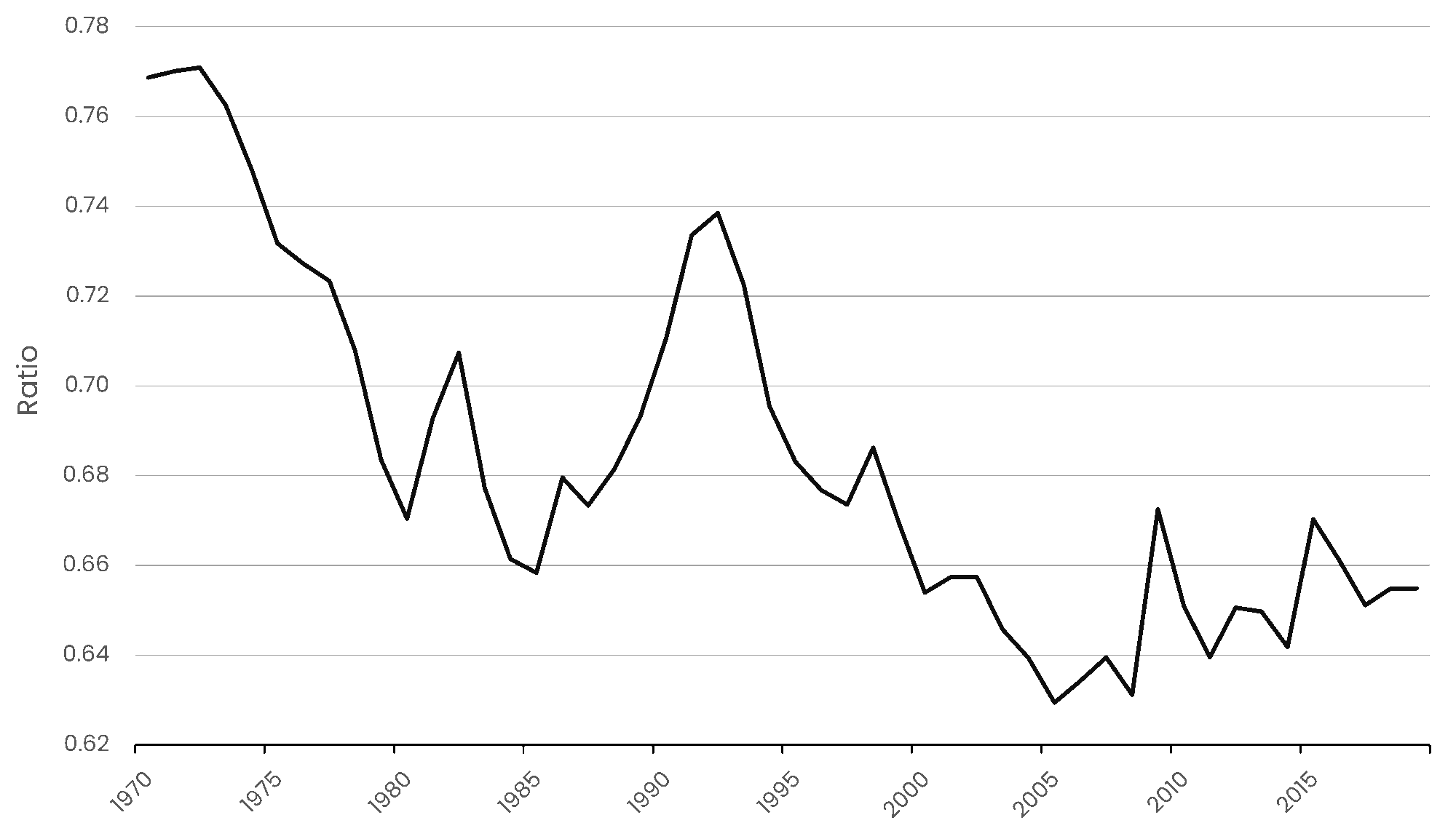

Historical trends reinforce this structural analysis. From the postwar period until the 1970s, Canada’s labour share of income peaked around 77 percent of GDP, supported by strong unions, a manufacturing base, and active state intervention. Beginning in the 1980s, however, labour’s share began its declining trend—reduced to 65 percent by 2019 (Figure 5). This drop coincided with the neoliberal policy reform paradigm (1980s–2000s), which included tax cuts, reduced public spending, privatization, labour market deregulation, and restrictions on unions—all of which weakened workers’ bargaining power and shifted a larger share of income toward capital. Trade liberalization, including NAFTA and China’s WTO accession, along with technological change and global value chain integration, further amplified this trend.

Figure 5 – Share of Labour Compensation in GDP at Current National Prices, Canada, 1970-2019

Source: University of Groningen and University of California, Davis, Share of Labour Compensation in GDP at Current National Prices for Canada [LABSHPCAA156NRUG], retrieved from FRED, Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis, August 16, 2025.

The structural implications are profound. As Eggertsson and Mehrotra (2014) demonstrate, rising inequality pushes r* lower due to reduced aggregate demand stemming from weaker workers’ power. Summers’ demand-side explanation of secular stagnation aligns with the neo-Keynesian model of secular stagnation by Eggertsson and Mehrotra where stagnation persists despite full employment, showing how structural shocks can maintain a persistently negative r*. Income inequality plays a central role by weakening aggregate demand in the face of full employment.

In the US since the 1970s, rising wealth concentration, and therefore increased savings behaviour by a few actors, has reduced the marginal propensity to consume, thereby depressing overall consumption. For the working-class, the pre-crisis reliance on household debt to sustain middle-class consumption collapsed after the subprime mortgage crisis (Eggertsson and Mehrotra), exacerbating this problem. Debt repayment and aging populations have further depressed consumption, leading to an excess of savings among the wealthy and insufficient investment opportunities, thus lowering the natural rate of interest. This model is also empirically supported by Rachel and Summers’ (2019) analysis, which shows that a savings glut, coupled with dysfunctions in the credit mechanism, have significantly contributed to secular stagnation. They argue that the more pressing constraint arises from inadequate demand, contrary to arguments supporting supply-side issues, where interest rate adjustments fail to rebalance savings and investment.

In Canada, these dynamics are compounded by high household debt and growing reliance on housing wealth to sustain consumption while household income has weakened. This fragile, asset-dependent consumption model is unsustainable and highly sensitive to rate shocks. As many factors push r* lower, monetary tools become less effective, leaving fiscal policy as the critical tool for macroeconomic stabilization.

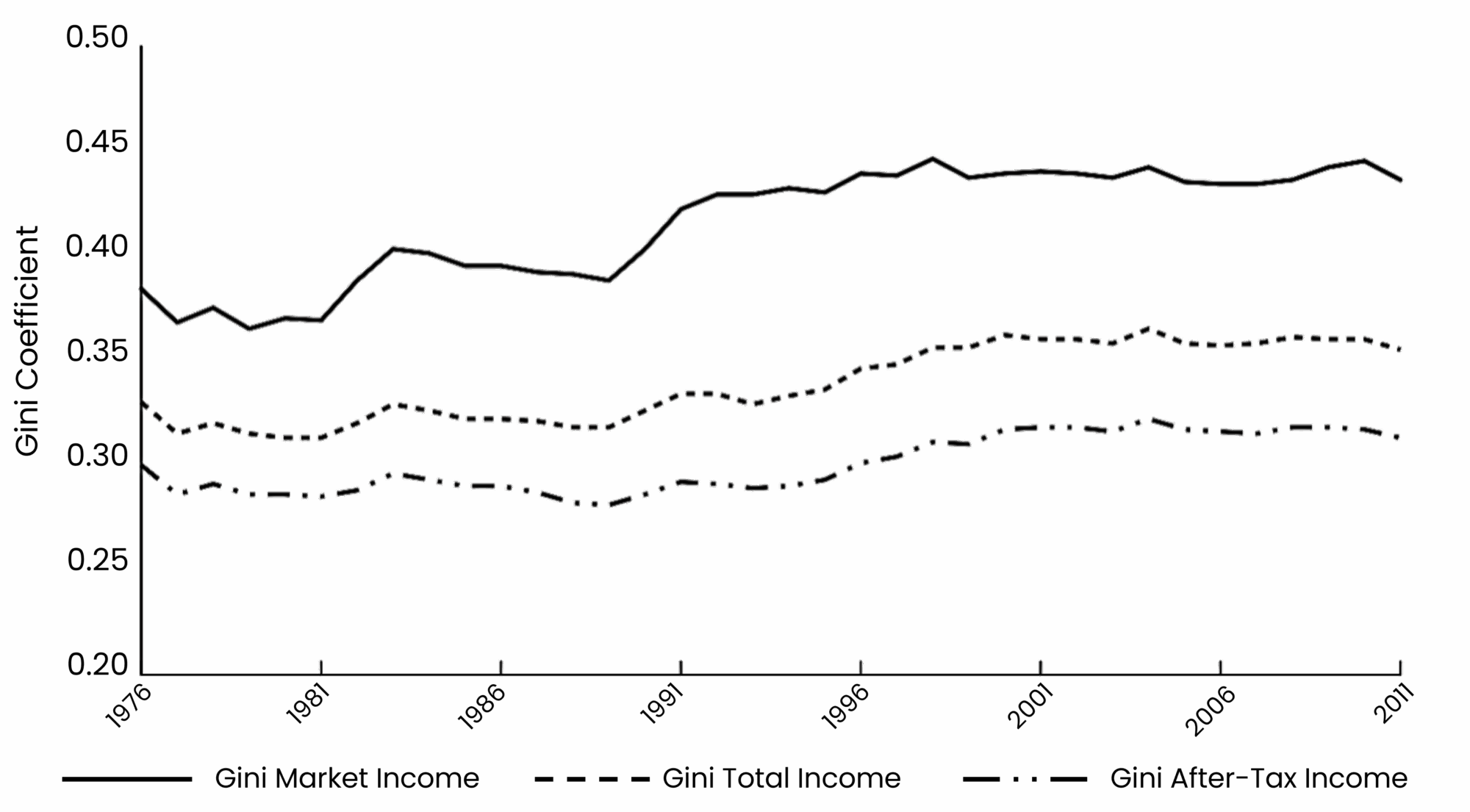

Through the period of the neoliberal economic paradigm, fiscal policy has still proven to be effective. As shown in Figure 6, fiscal redistribution has cushioned inequality, but market-driven disparities have continued to rise—outpacing the corrective reach of taxes and transfers. This highlights the need for stronger progressive and counter-cyclical fiscal policy to address structural inequality and reinforce inclusive growth.

Figure 6 – Income Inequality Before and After Transfers and Taxes, Canada, 1976-2011

Source: Inequality: The Canadian Story, Report, eds. David A. Green, W. Craig Riddell, and France St-Hilaire, Institute for Research on Public Policy, February 2017; Statistics Canada, CANSIM Table 202-0709.

Housing-Led Growth and Financialization: A Distorted Investment Path

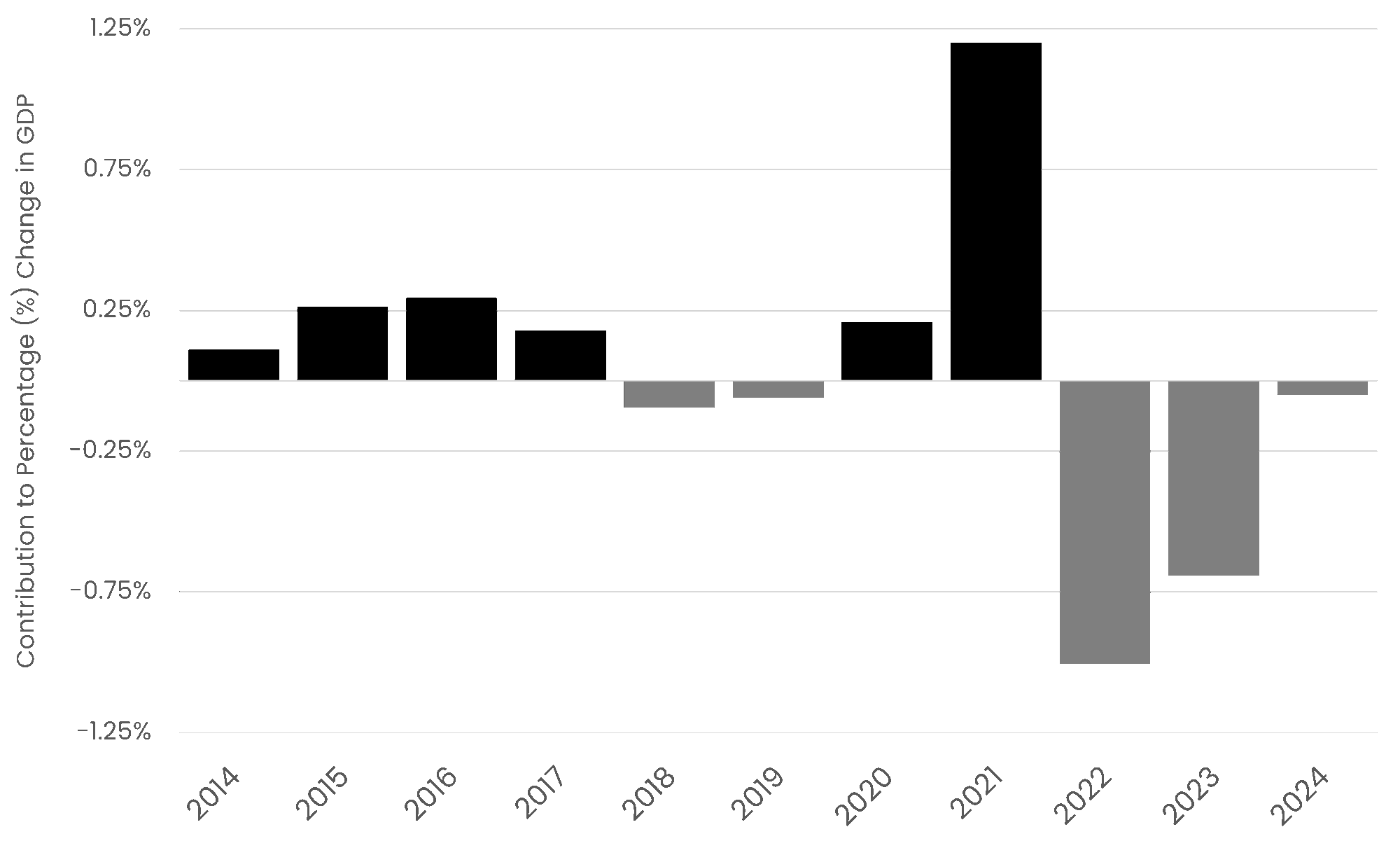

Another defining feature of Canada’s stagnation is its growing reliance on real estate and consumption—particularly housing-led investment—as the core drivers of GDP growth. Since 2015, household consumption and residential investment have consistently accounted for most growth contributions. The surge in residential structure spending contributions to Canada’s GDP in 2020–2021, illustrated in Figure 7, were driven by historically low interest rates, temporarily offset broader economic weakness and masked stagnation in real wage growth before crashing as quantitative tightening commenced in early 2022.

Figure 7 – Expenditure Contribution of Residential Structure to Annual Gross Domestic Product Growth, 2014–2024

Source: Statistics Canada, Table 36-10-0128-01, Contributions to annual percent change in real expenditure-based gross domestic product, Canada, annual.

This growth pattern is structurally fragile. The 2020 downturn exposed Canada’s dependence on private demand: business investment, net exports, and inventories all turned negative. In 2022, growth was driven not by productive capital formation, but by export recovery and inventory restocking—cyclical forces induced by the economic shock of the pandemic, unlikely to sustain long-term momentum. At the same time, residential investment began to decline, removing a major pillar of GDP support.

Capital formation in Canada remains skewed toward housing. While housing supported growth, enabled by periods of low interest rates until the pandemic shock, non-residential investment has remained subdued. Business investment in structures, machinery, and intellectual property has been limited in its contributions to growth over the past decade, suggesting weak foundations for future productivity gains.

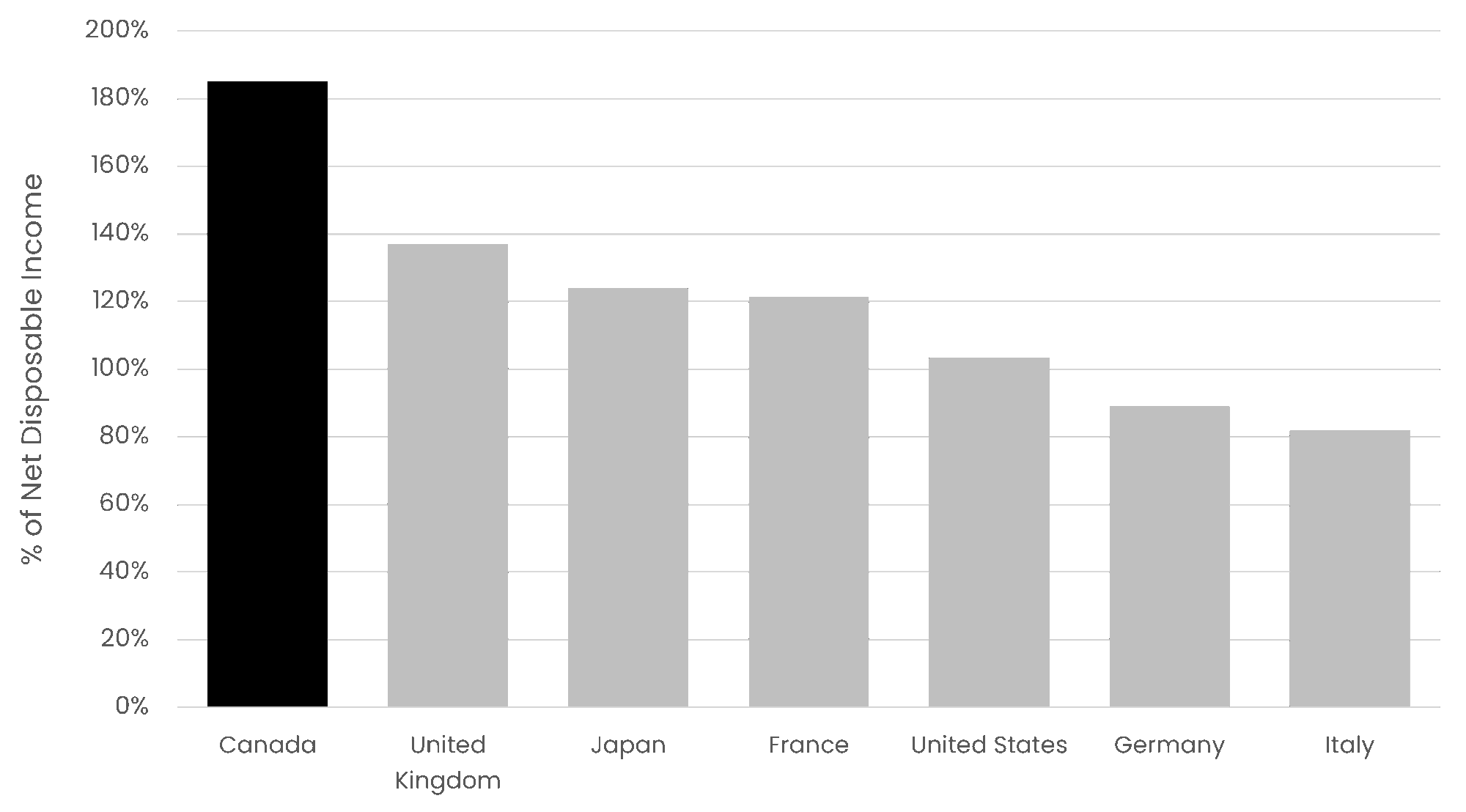

This “housing-led” growth model is deeply dependent on debt-fueled consumption and asset price inflation. Household debt reached 180 percent of disposable income in 2021—the highest among G7 economies (Figure 8). Canadians now owe $1.80 for every $1 of after-tax income in household debt. Debt-service ratios have also exceeded 15 percent in 2023 (Statistic Canada, Table: 11-10-0065-01), making households highly sensitive to interest rate changes.

Figure 8 – Household Debt Among G7 Countries, 2023

Source: Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development, National Accounts at a Glance (NAAG), OECD National Accounts Statistics.

Such high debt leverage also exposes Canada’s structural vulnerabilities, lending to secular stagnation. A correction in housing prices or tighter credit conditions would likely constrain household spending, with broader macroeconomic implications. Consumption is not wage-driven, but debt-financed—increasing risks to stability and resilience. These vulnerabilities are further compounded by inequality: rising home prices have crowded out low- and middle-income households from asset ownership, pushing them further into debt dependency and eroding their real purchasing power. Post-pandemic increases in savings and net wealth have been disproportionately concentrated among high-income households and homeowners.

The result is a distorted investment path: credit and policy incentives disproportionately favour static real estate over productivity-enhancing investment. In the long-run, this crowding-out effect undermines economic resilience, amplifies inequality, and leaves the economy highly vulnerable to financial shocks emanating from the housing sector, in addition to global financial shocks that can occur with higher frequency and uncertainty.

In Canada, these dynamics are compounded by high household debt and growing reliance on housing wealth to sustain consumption. This fragile, asset-dependent consumption model is unsustainable and highly sensitive to rate shocks. As many factors push r* lower, monetary tools become less effective, leaving fiscal policy as the critical tool for macroeconomic stabilization.

Without a concerted effort to address housing financialization and redistribute income, the economy risks settling into a stagnation trap—where weak demand perpetuates low investment, creating a self-reinforcing cycle of low growth, low inflation, and persistent output gaps. Escaping this trap requires proactive fiscal policy, including targeted transfers to low-income households, stronger labour protections, and a policy framework centered on inclusive, demand-led growth.

2. Labour, Wages, and Worker Power

The increase in income inequality in Canada is largely due to the long-run erosion of worker bargaining power. Following the frameworks of Stansbury & Summers (2020), Borsato (2021), and Storm (2023), declining labour power has contributed to weakened demand, underinvestment, and stagnation, despite low unemployment.

Workers have lost bargaining power due to lower rates of membership, and thus their share of labour income has decreased while corporate profits have increased in recent decades. These trends stem from a critical structural issue of rentier capitalism and financialization while labour is marginalized due to economic shifts from industrial manufacturing to service industries. This sectoral shift has also exacerbated employment instability, wage stagnation, and job quality deterioration as work in these relatively newer service industries have historically lower unionization rates. Despite substantial GDP growth contributions from the service sector, the shift has had a limited effect on employment levels and wages.

Borsato (2021) and Storm (2023) provide further evidence that declining worker power and growing income inequality generate macroeconomic imbalances, hampering growth and perpetuating inequality. Borsato (2021) strengthens this demand-side interpretation by showing that a persistent shift of income to the top reduces firms’ incentives to innovate. When most new income accrues to high-saving households, the returns on risky R&D investments fall, leading to reduced technological investment and stalled productivity growth. To restart growth, income redistribution and restructured incentive mechanisms are necessary.

Building on Borsato’s insights, Storm (2023) challenges both Gordon’s (2014) technology and demography thesis and Summers’ (2014) interest-rate-driven demand gap explanations. Storm demonstrates that secular demand stagnation is the product of policy-induced macroeconomic imbalances rooted in rising income for top recipients and wealth inequality. Trends in the Eurozone and beyond demonstrate how declining share of labour income, declining corporate investment, and fiscal austerity have created a cycle of “stagnant growth, distributional imbalance, and low inflation.” This cycle lends to stagnation for demand as it leads to suppressed growth and exacerbated inequality. This framework also offers valuable insights for the Canadian economy where stronger labour institutions vis-à-vis the United States have faced similar effects under the neoliberal paradigm.

Labour Institutions in Comparative Perspective

Over the past four decades, Canada and the United States have shared a high degree of cultural and policy synchronization, driven by economic spillovers and deeply integrated social and commercial ties. Although both Canada and the United States have experienced common global shocks, from technological disruption to trade liberalization, their institutional responses have diverged significantly.

In the US, a systematic assault on organized labour since the Reagan administration has driven down private-sector union density sharply—from 34 percent to 8 percent for men and from 16 percent to 6 percent for women between 1973 and 2007. During the same period, wage inequality in the private sector rose by over 40 percent. (Western and Rosenfeld, 2011) The decline in union membership is widely recognized as a key structural driver of rising wage inequality in the US and its erosion of labour’s power (Van Heuvelen 2018; Mishel 2021; Fortin, Lemieux, and Lloyd 2021). Some studies estimate that declining union density alone accounted for roughly one-third of the rise in wage inequality from the 1980s to 1990s (Western and Rosenfeld, 2011; Farber, et al., 2021).

In contrast, Canada has maintained comparatively higher and more stable union coverage. As of 2023, overall collective bargaining coverage stands at approximately 30 percent, versus 11 percent in the US, with private-sector coverage at 15 percent (Statistics Canada, Catalogue no. 14-28-0001-X, ISSN: 2818-1247)—more than double the US rate. Studies (e.g., Lemieux, 2006; Card et al., 2015) demonstrate that union presence in Canada has significantly compressed wage differentials: collective bargaining explains up to 7.9 percent of the reduction in overall wage inequality, compared to 3.5 percent in the US. This compression effect is one reason why Canada has experienced a more modest rise in wage inequality compared to the US, despite facing similar global and technological headwinds.

These institutional differences have had profound social and political consequences. In Canada, more resilient labour institutions have served as a stabilizing force, tempering populist, anti-establishment socioeconomic dislocations by preserving bargaining power for middle- and lower-income workers, influencing redistributive policy, and contributing to a more stable electoral center. The contrast between the two countries underscores the critical role of labour institutions in cushioning economic shocks, lending to comparatively more robust demand and productivity as a result of higher demand.

Declining Union Coverage and Reduced Spillover Effects

Despite their comparative strength vis-à-vis the US, Canada’s labour institutions have undergone a slow erosion in bargaining strength, particularly in the private sector. Overall union membership fell from about 37.6 percent in 1981 to around 30 percent by 2023, with private-sector coverage from roughly 21.3 percent in 1997 to 15.5 percent in 2023 (Figure 9). As shown in Figure 10, by 2022 only about 25 percent of men and 20 percent of women in the commercial sector remained unionized, compared to nearly 70 percent in the non-commercial sector. This decline is most pronounced in high-productivity, capital-intensive sectors, and has been compounded by the rise of non-standard, precarious employment, especially in services. Bargaining coverage fell in every province but Prince Edward Island between 1997 and 2023.

Figure 9 – Collective Bargaining Coverage Rate, Canada, 1997-2023

Source: Statistics Canada, Labour Force Survey, custom tabulation, Catalogue no. 14-28-0001-X; Due to rounding, estimates and percentages may differ slightly between different Statistics Canada products, such as analytical documents and data tables.

Figure 10 – Percentage of Employees who are Union Members, by Sex and Sector, Canada, 1981-2022

Source: Statistics Canada, Survey of Work History, 1981; Labour Force Survey, May 1997 and May 2022; Unionization in Canada, 1981 to 2022, René Morissette. DOI: 10.25318/36280001202201100001 eng.

This decline has reduced the “spillover” effect unions exerted on non-union firms to maintain wage standards across related sectors. This dynamic shifted wage-setting power from workers to firms, increasing wage dispersion and eroding labour’s share of national income. Fortin, Lemieux and Lloyd (2021) and Green et al. (2023) show that union presence has historically raised wages even outside of collective bargaining, through benchmarking (employers match union-set norms to retain talent), threat effects (firms raise wages to compete with unionization), and norm diffusion (union wage norms spill across the labour market culturally and institutionally), whereby union wage standards influence broader labour market practices. The erosion of unions contributes significantly to rising inequality with the loss of this economic power. As Gunderson (2022) argues, unions remain an irreplaceable tool for shaping wage norms and supporting inclusive growth.

3. The Profit–Investment Disconnect

Lastly, income and wealth inequality do not merely skew the social pie; they break the pipeline that directs profits to productive investment, freezing innovation and locking advanced capitalist economies, including Canada into, secular stagnation. Income inequality is compounded by the antithesis of high corporate profits and declining investment, despite profitability reaching historic peaks. According to the macroeconomic accelerator effect, investment depends more on expected demand or income conditions—high demand and high GDP nominally mean high investment. However, when income shifts toward high-saving households or retained earnings, and expected demand remains weak, investment has been found to remain weak and even low interest rates fail to stimulate investment. (Borsato, 2021)

The disconnect between record-high corporate profits and weak capital investment—a defining feature of secular stagnation—indicates that financial surpluses are not being converted into productive capacity. Despite sustained profitability, Canadian firms have reduced per-worker investment since 2015, especially in areas vital to innovation and future productivity, such as machinery and equipment (M&E), intellectual property products (IPP), as well as in traditional areas, such as non-residential and engineering structures (Robson and Bafale, 2023). As Robson and Bafale (2022) notes, “a country’s stock of non-residential buildings, engineering infrastructure, M&E, and IPP is critical to its ability to generate output and incomes. But Canada’s capital stock is barely growing, and not keeping pace with its workforce.” In 2024, Canadian workers were projected to receive just 66 cents in new capital for every dollar invested across the OECD, and only 55 cents for every U.S. dollar. (Robson and Bafale, N. 666, 2024) This reflects a persistent profit–investment gap: Canadian firms are not translating retained earnings into productive capital formation despite abundant credit.

Stagnation Feedback Loop and Demand Leakage

The underlying cause for the profit-investment disconnect is income inequality. As wealth concentrates in high-saving households and corporations—who have a lower marginal propensity to consume than middle- and low-income households, consumption demand remains weak, dragging down overall aggregate demand. This creates a feedback loop: the declining labour share and sluggish wage growth further erode household purchasing power, while rising corporate profits are not reinvested in productive assets but instead accumulate as cash reserves, stock buybacks, or dividend payouts. The result of this feedback loop is aggregate-demand leakage: profits do not translate into broader spending that would validate new investment. Consequently, innovation investment slows, undermining long-term productivity growth and potential output, while wages remain stagnant.

Firms delay investment in innovation such as R&D and technology adoption due to weak consumption growth and risk aversion under demand constraints. Since innovation is itself a key engine of growth, Benigno and Fornaro (2022) formalize this in their stagnation trap model, where pessimistic expectations today suppress innovation and capital expenditure, which in turn validate low-growth expectations tomorrow. In this context, excess savings fail to stimulate recovery because the returns on R&D are too low to incentivize private investment. Unlike Keynesian liquidity traps where savings are preferred to investment due to the expectation of acute demand shocks, the core issue becomes worsening systemic income distribution which prevents savings from finding productive, high-return outlets. As a result, economies become trapped in a feedback loop low-growth equilibrium where insufficient aggregate demand fails to absorb potential output, weak innovation curbs productivity gains, and inequality continues to intensify—locking the economy into a stagnation trap.

Conclusion

Income inequality is an active constraint on economic dynamism and has contributed to stagnation in Canada. Wage suppression, weak social transfers, and regressive taxes have eroded household incomes, leading to a structurally demand-deficient economy in the Canadian context, but the same trends can also be found in other capitalist economies. The turn to debt and housing wealth, especially in the Canadian context, has masked this fragility, but itself has become a vulnerability and cannot sustain growth indefinitely. Exiting structural stagnation requires addressing the core contradiction between Canada’s distributional regime and its growth model. This means restoring the wage–productivity link, reorienting investment toward productivity-enhancing activities, and rebuilding the social architecture that supports economic inclusion.

The effectiveness of monetary policy is diminishing but retains short-term adjustment capacity. Interest rate transmission and inflation expectations management remain effective in Canada: rate hikes have cooled the housing market, curbed overheating inflation, stabilized market expectations, and influenced the exchange rate via interest differentials, thereby affecting exports and import-driven inflation. However, long-term effects are increasingly marginal. Beyond a lower r* and reduced policy space, key constraints include weakened consumption elasticity—highly indebted households show muted response to rate changes due to low marginal propensity to consume—dampening monetary policy’s ability to stimulate spending. Business investment is largely unresponsive to interest rates as investment is constrained not by financing costs but by weak demand expectations. A preference for safe assets and distorted financial markets further limit effectiveness—monetary easing may inflate asset bubbles rather than drive real investment. Monetary policy can still guide Canada’s economic trajectory, but without structural reform, its impact will continue to diminish and its costs will rise.

The Pandemic as Both Crisis and Opportunity

The COVID-19 pandemic catalyzed a multi-dimensional shift in Canada’s economic and political landscape. First, it reasserted the essential role of the state through unprecedented public spending and institutional intervention, shattering the triad of low taxes, small government, and the omnipotence of markets. Second, it exposed the limits of market-centric governance, revealing the failure of neoliberal policies to deliver resilience or equity. Third, it laid bare deep structural inequalities, amplifying the vulnerabilities of low-income and precarious workers. For example, low-income, precarious, and disproportionately racialized and female workers bore the brunt of the crisis, while wealthier asset-owning groups recovered quickly, resulting in a clear “K-shaped recovery”: rapid gains at the top, deepening hardship at the bottom (Osberg, 2021). Canada’s social safety net, long under strain, was forced to act as a macroeconomic stabilizer. Emergency programs like the Canada Emergency Response Benefit and other wage subsidies proved essential, but also revealed the fragility and insufficiency of existing systems such as Employment Insurance and provincial welfare. Lastly, Canada’s fiscal response reshaped political consciousness, fueling rising demands for stronger collective institutions and more inclusive economic governance.

The neoliberal paradigm has failed to align growth with equity, unable to resolve the very structural imbalances and demand shortfalls it has helped create. The shared fate during the pandemic has catalyzed a shift in collective consciousness is underway across Canadian society, particularly among Millennials and Gen Z. These cohorts entered adulthood in the aftermath of the 2008 Global Financial Crisis, endured a decade of job market precarity, and then bore the brunt of pandemic job losses. The contours of this evolving collective consciousness include: 1) declining faith in a “self-correcting market”; 2) rising expectations for state-led redistribution and public investment; 3) growing recognition that individual security depends on collective institutions and increasing demand for a more active role by the state in supporting growth, productivity, and economic resilience; 4) diminishing tolerance for structural inequality (Abacus Data, 2018; CanTrust Index, 2025). This awakening reflects a broader response to lived experiences of inequality, intergenerational injustice, and eroding public institutions. It signals a call for a renewed social contract and a more inclusive economic model. This is a powerful generational shift in expectations—one that demands a corresponding shift in policy thinking. To move from pandemic emergency response to long-term economic renewal, Canada must treat the crisis as a catalyst for structural reform.

Toward Inclusive Growth

The focus of policy should therefore shift from primarily relying on monetary or interest rate adjustments to addressing the fundamental distributional imbalances within the economy that have led to stagnation. To reignite growth, Canada must build a sustainable model of economic development and governance centered on “inclusive growth”. Promoting economic growth while ensuring its benefits are more broadly shared—especially by low- and middle-income groups—is essential to reducing inequality, strengthening social cohesion, and advancing equal opportunity. “Inclusive growth” marks a normative shift away from the neoliberalism focused on market neutrality and procedural fairness.

Over the past decade, a range of influential reports from the OECD, World Bank, IMF, G20, UN, and other international organisations have elevated inclusive growth to a central position in global economic discourse (OECD 2017; IMF 2018; IMF G-20 SSBIG Reports 2018–2024; World Bank 2025; Ostry 2018; Johnson 2021; Davoodi et al. 2021; Agarwal 2024). Canada has been an active participant in these discussions. The concept has attracted attention not only from scholars and policy analysts but also from Canadian corporate leaders, industry associations, provincial and federal policymakers (e.g. Global Affairs Canada 2017), and trade unions. Key ideas in the inclusive growth agenda—broadening economic participation and ensuring a fairer distribution of the gains from growth—are reflected in national policy frameworks such as Growth that Works for Everyone (Global Affairs Canada 2017).

In practice, inclusive growth centers on four key priorities: (1) expanding opportunity (through better education, skills training, and access to jobs for disadvantaged groups); (2) improving distribution of economic benefits (by reducing income and wealth inequality so that the gains from growth flow more toward lower-income households); (3) enhancing institutional fairness (via stronger social protection, progressive taxation, and fair labour markets); and (4) ensuring sustainability (by avoiding growth at the expense of environmental or social stability). This approach is grounded in both empirical evidence and normative judgment endorsed by economists such as Nobel Laureate Joseph Stiglitz (2015, 2025), Dani Rodrik (2014), and Thomas Piketty (2022): inequality and growth are deeply interconnected, and growth that is not inclusive is ultimately unsustainable.

Grounded in egalitarian liberalism and public goods theory, it emphasizes outcome-oriented structural equity, going beyond formal equality of opportunity to focus on whether outcomes meaningfully improve the conditions of the most disadvantaged.

Pandemic-era public spending reframed the state as the “protector of last resort” against market failure and structural inequality, marking a shift from neoliberal approach to neoliberal view of government’s role in growth and redistribution toward a new governance framework that places greater emphasis on broader state-led policies—most notably expanded public investment—to drive inclusive growth, counter weak private demand, and strengthen long-term supply potential.

Economic institutions are not neutral or value-free; they reflect underlying political philosophies, competing views of justice, and of the common good. Specific policy goals are often shaped by utilitarian reasoning and economic efficiency; fundamentally speaking, distributional systems embody choices about justice, power structure, and social priorities. They embody the kind of society we wish to build, and ultimately, the way of life we wish to live. Rethinking distributional means shifting from “raising GDP and then redistributing it” toward structuring the economy from the outset in a way that distributes opportunity and reward more equitably. Inclusive growth, in this sense, requires structurally embedding fairness into the foundations of growth itself.

Redistribution is the precondition for demand recovery, investment revitalization, and long-term economic stability. Canada must rebuild labour income, expand public investment, and implement aggressive fiscal policies aimed at reducing inequality and stimulating demand. Compared to the objective of prioritizing market efficiency alone, structural redistribution and investment-led resilience must be treated as macroeconomic imperatives. Policy should aim to ensure shared prosperity and reduce inequality.

References

Click to expand for a full list of references.

Agarwal, Ruchir. “What Is Inclusive Growth?” Finance & Development, Mar. 2024, International Monetary Fund, https://www.imf.org/en/Publications/fandd/issues/2024/03/B2B-what-is-inclusive-growth-Ruchir-Agarwal.

Benigno, Gianluca, and Luca Fornaro. “Stagnation Traps.” The Review of Economic Studies, vol. 85, no. 3, 2018, pp. 1425-1470. DOI: 10.1093/restud/rdx063.

Borsato, Andrea. “An Agent-based Model for Secular Stagnation in the USA: Theory and Empirical Evidence.” Journal of Evolutionary Economics, vol. 32, no. 4, 2022, pp. 1345-1389. DOI: 10.1007/s00191-022-00772-9.

Card, David, Thomas Lemieux, and W. Craig Riddell. “Unions and Wage Inequality: The Roles of Gender, Skill and Public-Sector Employment.” IZA Discussion Paper 11964, 2018.

Das, Anupam, Ian Hudson, and Mark Hudson. “Unionization Rates, Inequality and Poverty in Canadian Provinces 2000-2020.” Capital & Class, 2024, pp. 1-26. DOI: 10.1177/03098168241269173.

Davoodi, Hamid R., Peter J. Montiel, and Anna Ter-Martirosyan. Macroeconomic Stability and Inclusive Growth. IMF Working Papers, vol. 2021, no. 081, International Monetary Fund, 19 Mar. 2021. DOI: https://doi.org/10.5089/9781513574363.001.

Eggertsson, Gauti B., and Neil R. Mehrotra. A Model of Secular Stagnation. NBER Working Paper 20574, 2014. DOI: 10.3386/w20574.

Farber, H. S., Herbst, D., Kuziemko, I., & Naidu, S. (2021). Unions and Inequality Over the Twentieth Century: New Evidence from Survey Data. Quarterly Journal of Economics, 136(3), 1325–1385. DOI: 10.1093/qje/qjab012

Agarwal, Ruchir. “What Is Inclusive Growth?” Finance & Development, Mar. 2024, International Monetary Fund, https://www.imf.org/en/Publications/fandd/issues/2024/03/B2B-what-is-inclusive-growth-Ruchir-Agarwal.

Benigno, Gianluca, and Luca Fornaro. “Stagnation Traps.” The Review of Economic Studies, vol. 85, no. 3, 2018, pp. 1425-1470. DOI: 10.1093/restud/rdx063.

Borsato, Andrea. “An Agent-based Model for Secular Stagnation in the USA: Theory and Empirical Evidence.” Journal of Evolutionary Economics, vol. 32, no. 4, 2022, pp. 1345-1389. DOI: 10.1007/s00191-022-00772-9.

Faucher, Guyllaume, et al. Potential Output and the Neutral Rate in Canada: 2023 Reassessment. Bank of Canada Staff Analytical Note 2023-6, 2023.

Fortin, Nicole M., Thomas Lemieux, and Neil Lloyd. Labour Market Institutions and the Distribution of Wages: The Role of Spillover Effects. NBER Working Paper 28375, 2021. DOI: 10.3386/w28375.

Global Affairs Canada. Growth That Works for Everyone. 1 Nov. 2017, https://www.international.gc.ca/world-monde/issues_development-enjeux_developpement/inclusive_growth-croissance_inclusive/index.aspx?lang=eng.

Gordon, Robert J. 2015. “Secular Stagnation: A Supply-Side View.” American Economic Review 105 (5): 54–59. DOI: 10.1257/aer.p20151102

Green, D. A., Riddell, W. C., & St-Hilaire, F. (Eds.). (2016). Income Inequality: The Canadian Story. Volume V, The Art of the State Series. Institute for Research on Public Policy (IRPP).

Green, David A., Ben M. Sand, Iain G. Snoddy, and Jeanne Tschopp. The Impact of Unions on Non-union Wage Setting: Threats and Bargaining. Vancouver School of Economics Working Paper, 2023.

Gunderson, Morley. Minimum Wages: Good Politics, Bad Economics? Northern Policy Institute, 2014.

Ianchovichina, Elena. “Chapter 8. What Is Inclusive Growth?” Commodity Price Volatility and Inclusive Growth in Low-Income Countries, International Monetary Fund, 2012.

International Labour Organization. Policy Measures to Address Inequalities and Increase the Labour Income Share. G20 Technical Paper no. 2, Apr. 2025, https://www.ilo.org/sites/default/files/2025-04/G20_TechnicalPaper%232_Policy%20measures%20to%20address%20inequalities%20and%20increase%20the%20labour%20income%20share.pdf

International Monetary Fund. G-20 Reports on Strong, Sustainable, Balanced, and Inclusive Growth (SSBIG). International Monetary Fund, 2018-2024, https://www.imf.org/en/Publications/SPROLLs/SSBIG-reports.

International Monetary Fund. Making Growth Inclusive: Reducing Inequality Can Open Doors to Growth and Stability. 2018, https://www.imf.org/external/pubs/ft/ar/2018/eng/spotlight/making-growth-inclusive/.

Johnson, Simon, and Priscilla S. Muthoora. The Political Economy of Inclusive Growth: A Review. IMF Working Papers, vol. 2021, no. 082, International Monetary Fund, 19 Mar. 2021. DOI: https://doi.org/10.5089/9781513574189.001.

Lemieux, Thomas. “Unions and Wage Inequality in Canada and the United States.” Differences and Changes in Wage Structures, edited by Richard B. Freeman and Lawrence F. Katz, U of Chicago P, 1995, pp. 109-148.

Mishel, Lawrence. The Enormous Impact of Eroded Collective Bargaining on Wages. Economic Policy Institute, 8 Apr. 2021, https://www.epi.org/publication/eroded-collective-bargaining/.

Morissette, René. “Unionization in Canada, 1981 to 2022.” Economic and Social Reports, no. 36‑28‑0001, Statistics Canada, 23 Nov. 2022. DOI:10.25318/36280001202201100001‑eng. https://www150.statcan.gc.ca/n1/pub/36-28-0001/2022011/article/00001-eng.htm

OECD. Policies for Stronger and More Inclusive Growth in Canada. OECD Publishing, 2017. https://www.oecd.org/content/dam/oecd/en/publications/reports/2017/06/policies-for-stronger-and-more-inclusive-growth-in-canada_g1g7b949/9789264277946-en.pdf

Osberg, Lars. From Keynesian Consensus to Neoliberalism to the Green New Deal: 75 Years of Income Inequality in Canada. Canadian Centre for Policy Alternatives, 2021.

Osberg, Lars. The Age of Increasing Inequality: The Astonishing Rise of Canada’s 1%. Updated ed., James Lorimer & Company, 2024.

Ostry, Jonathan D., et al. “Growth or Inclusion?” or “The Economics of Promoting Inclusive Growth.” Finance & Development, June 2018, International Monetary Fund, https://www.imf.org/en/Publications/fandd/issues/2018/06/economics-of-promoting-inclusive-growth-ostry.

Piketty, Thomas. A Brief History of Equality. Translated by Steven Rendall, Harvard University Press, 2022.

Purdye, Alex. Canadian Grocery Profitability: Inflation, Wages and Financialization. Broadbent Institute, 2023.

Rachel, Łukasz, and Lawrence H. Summers. “On Falling Neutral Real Rates, Fiscal Policy, and the Risk of Secular Stagnation.” Brookings Papers on Economic Activity, Spring 2019, pp. 1-66.

Rammelt, Crelis F., and Joyeeta Gupta. “Inclusive Is Not an Adjective, It Transforms Development: A Post-Growth Interpretation of Inclusive Development.” Environmental Science & Policy, vol. 124, 2021, pp. 144–155. Elsevier, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.envsci.2021.06.012.

Robson, William B. P., and Bafale, Mawakina. Decapitalization: Weak Business Investment Threatens Canadian Prosperity. Commentary No. 625, C.D. Howe Institute, 2022. C.D. Howe Institute, https://www.cdhowe.org/public-policy-research/decapitalization-weak-business-investment-threatens-canadian-prosperity

Robson, William B.P., and Mawakina Bafale. Underequipped: How Weak Capital Investment Hurts Canadian Prosperity and What to Do about It. Commentary No. 666, C.D. Howe Institute, 2024. https://cdhowe.org/publication/underequipped-how-weak-capital-investment-hurts-canadian-prosperity-and-what/

Robson, William B.P., and Mawakina Bafale. Working Harder for Less: More People but Less Capital Is No Recipe for Prosperity. Commentary No. 647, C.D. Howe Institute, 2023. https://www.cdhowe.org/public-policy-research/working-harder-less-more-people-less-capital-no-recipe-prosperity

Rodrik, Dani. “How Does Equality Affect Efficiency?” World Economic Forum, Dec. 2014, World Economic Forum, https://www.weforum.org/stories/2014/12/how-does-equality-affect-efficiency.

Rodrik, Dani. “Good and Bad Inequality: The Economics of the Equality–Growth Trade-Off.” Project Syndicate, Dec. 2014, https://www.project-syndicate.org/commentary/equality-economic-growth-tradeoff-by-dani-rodrik-2014-12.

Speer, Sean; Fagan, Drew; and Glozic, Luka. A Post Pandemic Growth Strategy for Canada. Ontario 360 Policy Paper, December 17, 2020. Ontario 360. https://on360.ca/policy-papers/a-post-pandemic-growth-strategy-for-canada/

Stansbury, Anna, and Lawrence H. Summers. “The Declining Worker Power Hypothesis: An Explanation for the Recent Evolution of the American Economy.” Brookings Papers on Economic Activity, Spring 2020, pp. 1-77. DOI: 10.3386/w27193.

Statistics Canada, 2024. Quality of Employment in Canada: Collective Bargaining Coverage Rate, 2023. Release date: October 15, 2024. https://www150.statcan.gc.ca/n1/pub/14-28-0001/2024001/article/00010-eng.htm

Stiglitz, Joseph E. The Origins of Inequality, and Policies to Contain It. Oxford University Press, 2025. DOI:10.1093/oso/9780198799580.003.0004.

Stiglitz, Joseph E. “Inequality and Economic Growth.” The Political Quarterly, vol. 86, suppl. 1, Dec. 2015, pp. 134-155. DOI:10.1111/1467-923X.12237.

Stiglitz, Joseph E. “Nobel Laureate Joseph Stiglitz on the Price of Inequality” Columbia News, 14 June 2012, https://news.columbia.edu/news/nobel-laureate-joseph-stiglitz-price-inequality.

Storm, Servaas. The Secular Stagnation of Productivity Growth. INET Working Paper 108, 2019.

Summers, Lawrence H. “Low Equilibrium Real Rates, Financial Crisis, and Secular Stagnation.” Across the Great Divide: New Perspectives on the Financial Crisis, edited by Martin Neil Baily and John B. Taylor, Hoover Institution Press, 2014, pp. 37-50.

Summers, Lawrence H. “U.S. Economic Prospects: Secular Stagnation, Hysteresis, and the Zero Lower Bound.” Business Economics, vol. 49, no. 2, 2014, pp. 65-73. DOI: 10.1057/be.2014.13.

VanHeuvelen, Tom. “Moral Economies or Hidden Talents? A Longitudinal Analysis of Union Decline and Wage Inequality, 1973–2015.” Social Forces, vol. 97, no. 2, Dec. 2018, pp. 495–530. Oxford University Press, https://doi.org/10.1093/sf/soy045.

Wilkins, Carolyn A. “Monetary Policy and the Underwhelming Recovery.” Speech to the CFA Society Toronto, Bank of Canada, 22 Sept. 2014.

Wilkins, Carolyn A. “Our Economic Destiny: Written in R Stars?” Remarks before the Economic Club of Canada, Toronto, February 5, 2020. Bank of Canada. https://www.bankofcanada.ca/2020/02/our-economic-destiny-written-in-r-stars/

Western, Bruce, and Jake Rosenfeld, 2011. “Unions, Norms, and the Rise in U.S. Wage Inequality,” American Sociological Review, vol. 76(4), pages 513–537. DOI: 10.1177/0003122411414817, http://asr.sagepub.com

World Bank. “Cabo Verde: Unlocking Inclusive Growth through Increased Resilience and Equal Opportunities.” World Bank, 23 June 2025, https://www.worldbank.org/en/news/press-release/2025/06/23/cabo-verde-unlocking-inclusive-growth-through-increased-resilience-and-equal-opportunities.

World Bank. “Building Momentum for Inclusive Growth in Nigeria.” World Bank, 12 May 2025, https://www.worldbank.org/en/news/press-release/2025/05/12/afw-nigeria-building-momentum-for-inclusive-growth.

World Bank. “New World Bank Report Highlights Four Pathways to Spur Job-Afe Growth in South Africa.” World Bank, 28 Feb. 2025, https://www.worldbank.org/en/news/press-release/2025/02/28/-new-world-bank-report-highlights-four-pathways-to-spur-job-afe-growth-in-south-africa.