Professor Mel Watkins delivered the following eulogy for political economist Abe Rotstein (1929 – 2015) on April 30th, 2015.

My dear friend Abe had lived so long. He kept teaching after his contemporaries had quit, and was still so sound of body and mind, that it seemed to me that he just might live forever.

We both joined the old Department of Political Economy at the University of Toronto more than 55 years ago and became the best of friends. We have so remained ever since. Our lives intersected personally, politically and intellectually.

At the beginning I was a faculty member and he was a graduate student, but I can say without exaggeration that he was my teacher. He had a remarkable breadth of interest, from economic history to political science, from anthropology to philosophy, theology to linguistics, and to the history of technology.

As many of us who are here today know, the sixties was the last great decade. There was a surge of a pent up Canadian nationalism. Abe was the leading theorist and scholar of that movement in English Canada, and one of its most prominent and innovative practitioners.

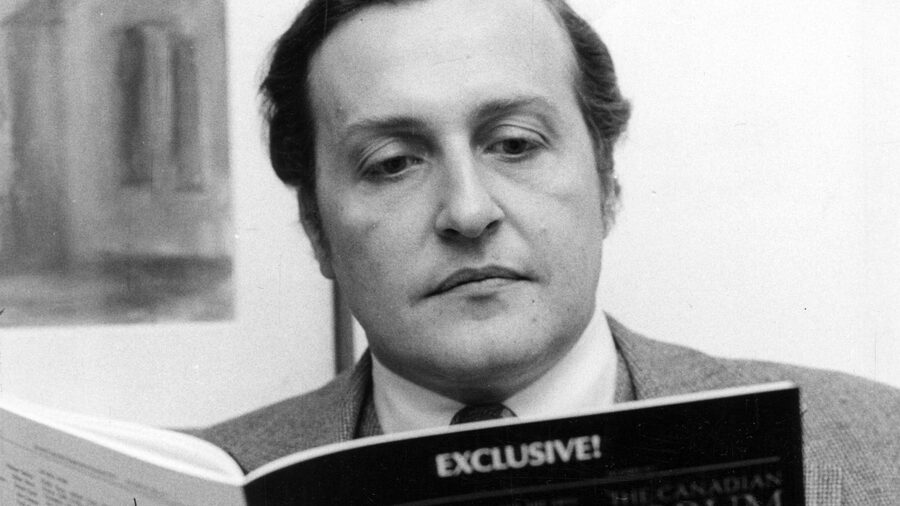

Abe became the editor of the then prestigious Canadian Forum. He founded the University League for Social Reform, which published a number of books. He was active in the teach-in movement on the University of Toronto campus against the American war in Vietnam. He supported Quebec’s right to self-determination.

He was a member of a federal government Task Force on Foreign Ownership. The task force, which offered policy recommendations to counter and regulate foreign ownership, included Ed Safarian and me from the University of Toronto. He was one of the founders of the Committee for an Independent Canada, which morphed into the Council of Canadians, and of the Canadian Institute for Economic Policy.

Abe was a dissenter from the conventional wisdom, with the conviction and courage it takes and, as often happens to dissenters, he was usually on the losing side. He understood that history is written by the winners, but he never lost his good cheer.

He was evidently not your conventional economist. He was that rare creature, a public intellectual.

Abe’s doctoral thesis on the fur trade, drew on the approaches of Karl Polanyi, whom he had studied with at Columba University and with whom he co-authored the book Dahomey and the Slave Trade, and of Harold Innis who haunted the halls of the Sidney Smith Building on the UofT campus. He taught Canadian economic history, occasionally European, and a course on Institutions and the Economy.

When the Department split into two departments, economics and political science, he was one of the economists who got a cross-appointment to political science. He became a Senior Fellow at Massey College and oversaw the Southam Journalism Fellowship Program. He participated in the weekly gathering of the famous McLuhan seminar and was closely involved with the Karl Polanyi Institute at Concordia University.

Abe wrote extensively, beautifully, and accessibly. He edited and co-edited a number of books. His 1973 book, The Precarious Homestead, captures brilliantly the mood of the times and his contribution to the great dialogue that was going on.

He leaves behind him two almost completed manuscripts. One is a book on the fur trade, his lifelong interest. The other is his magnum opus, perhaps best described by the title of a graduate seminar he gave in political science, The Apocalyptic Tradition in Western Political Thought.

When teaching evaluations were introduced, Abe consistently ranked year after year as one of the best teachers in the economics department. He was much respected by students who described him as a gentleman and a patient person.

His elegance was legendary. Our mutual friend Stephen Clarkson loved to introduce him as Count Rotstein.

He was a world-class punster; he swam in puns, as John Fraser of Massey College has put it. There’s a web site of the best 100 puns ever and Abe makes it for arguably his greatest pun: “Every dogma has its day.” Though “Buddy, can you spare a paradigm” is a close second.

I miss him terribly. He was that best of friends, a person who was always there for you. Our families knew and know each other. In recent times whenever I got together with him, we talked about our children and grandchildren. He was a good and wise person.

About two weeks ago, I sent him a piece I had written about soldiers coping with life in the trenches of the First World War. He e-mailed me back with his characteristic generosity: “A very touching piece, beautifully written. The human dimension gets lost as global forces and anonymous institutions jostle one another. I hope that you and Kelly are well and enjoying our long delayed spring. Life in Toronto is much the same but the sun and the daffodils help a lot. Best regards, Abe.”