Global Affairs Canada is conducting public consultations on a possible Canada-China Free Trade Agreement. Based on the record since China joined the World Trade Organization (WTO) in 2001, further liberalization of trade and investment on the current model would not benefit most Canadians.

Following the ground breaking work of Branko Milanovic at the World Bank, economists increasingly accept that the rules of the liberal global economy have produced both winners and losers. The big winners have been the top one percent around the world who have benefited from a global rise in corporate profits and senior executive incomes and, to a degree, workers in developing countries who have enjoyed rising real wages.

The big losers have been mid skilled workers in the advanced industrial countries who have experienced job losses and wage stagnation as manufacturing production and new manufacturing investment have shifted to low wage developing countries. Increased North-South trade, especially with China, now the workshop of the world, has exerted major downward pressures on wages and pushed surviving manufacturing operations in advanced economies to become much more capital intensive, further squeezing employment.

Since 2000, Canada has lost 547,000 manufacturing jobs. Real hourly wages in manufacturing have grown at a much lower rate than productivity, increasing by just 6.8% over the entire period from 2000 to 2016, or by well under 0.5% per year. While downward competitive pressures from low wage competition have been felt most directly and severely in the traded goods sector, they have been more widely experienced in industrial communities and throughout the economy as the blue-collar middle-class has been hollowed out.

There is far more to this dismal story than the rise of China, notably the over-valuation of the exchange rate of the Canadian dollar against the US dollar during the resource boom, and the failure of many Canadian manufacturers to restructure towards more innovative and higher value-added production on the model of Germany and Japan. But the trade deficit with China is a major factor behind the manufacturing crisis.

Canada has lost a significant share of the huge US market for manufactured goods to China. Between 2002 and 2016, the China share of all United States merchandise imports rose from 11% to 21%, while the Canadian share fell from 18% to 13% despite increased American imports of Canadian energy.

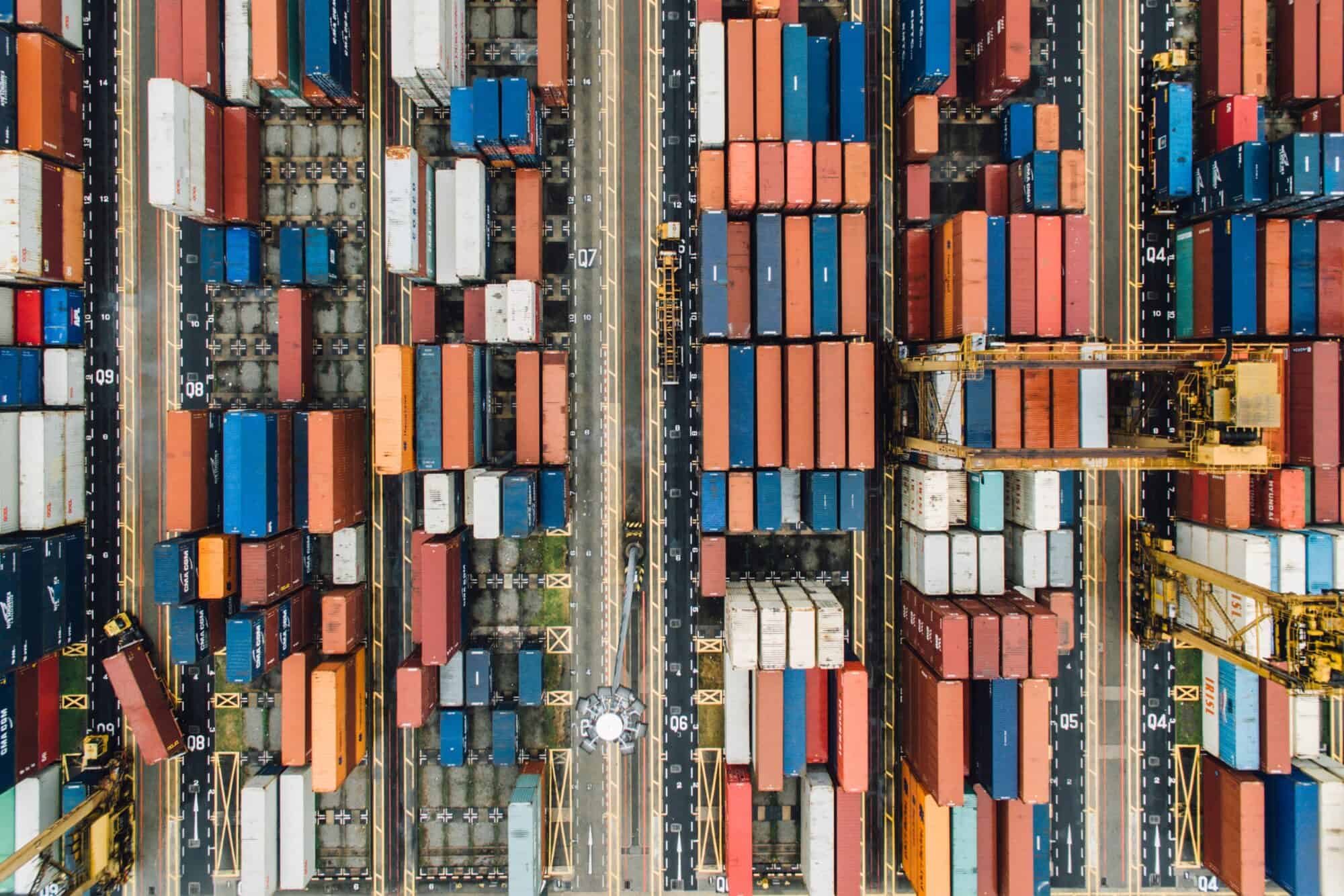

We currently run a large bilateral trade deficit with China of $44 billion in 2016. Exports amounted to $20.1 Billion, overwhelmingly made up of resources and raw materials, while imports from China amounted to three times as much as exports, $64.3 Billion. Our imports consist almost entirely of manufactured goods.

In principle, downward pressure on wages in the advanced industrial countries arising from trade with low wage countries should be offset by the new opportunities created by rising wages and expanding markets in the latter. This is true to a point. As Milanovic shows, wages and living standards have risen rapidly in China and other developing countries.

However, the latest International Monetary Fund (IMF) Global Economic Outlook notes that the share of wages in national income has fallen since 2000 in both developed and developing countries due to technological change, global trade patterns and the decline of unions. The labour share has mainly fallen in middle skill jobs in advanced economy industries subject to global competition, and in sectors in developing countries like China which participate in global value chains. Together with the decline of unions, this has contributed to the recent marked rise in inequality in most countries.

Research by the International Labour Organization (ILO) shows that the labour share of national income in China fell from an already low 54% in 2000 to 47% in 2011 since profits have risen much faster than wages. The tendency of wages to lag productivity in both the developed and developing world contributes to sluggish overall growth.

With respect to a possible Canada-China trade deal, we should challenge the artificial trade advantage China enjoys due to suppression of labour rights. This is a factor behind the low and falling wage share in that country and large trade imbalances.

As recently noted in the Globe and Mail by Ed Broadbent, China has not ratified the core international human rights provisions with respect to freedom of association and the effective recognition of the right to collective bargaining, and instead imposes government dominated unions on workers.

A key Canadian objective should also be to bring our manufacturing trade with China into much closer balance. Given the huge imbalance that exists under current rules, this would likely require more managed trade plus much more pro active Canadian industrial policies. As a planned economy, China might be open to sectoral managed trade arrangements.

When it comes to a Canada-China FTA, our economic relationship needs to be re-balanced rather than simply reinforced.