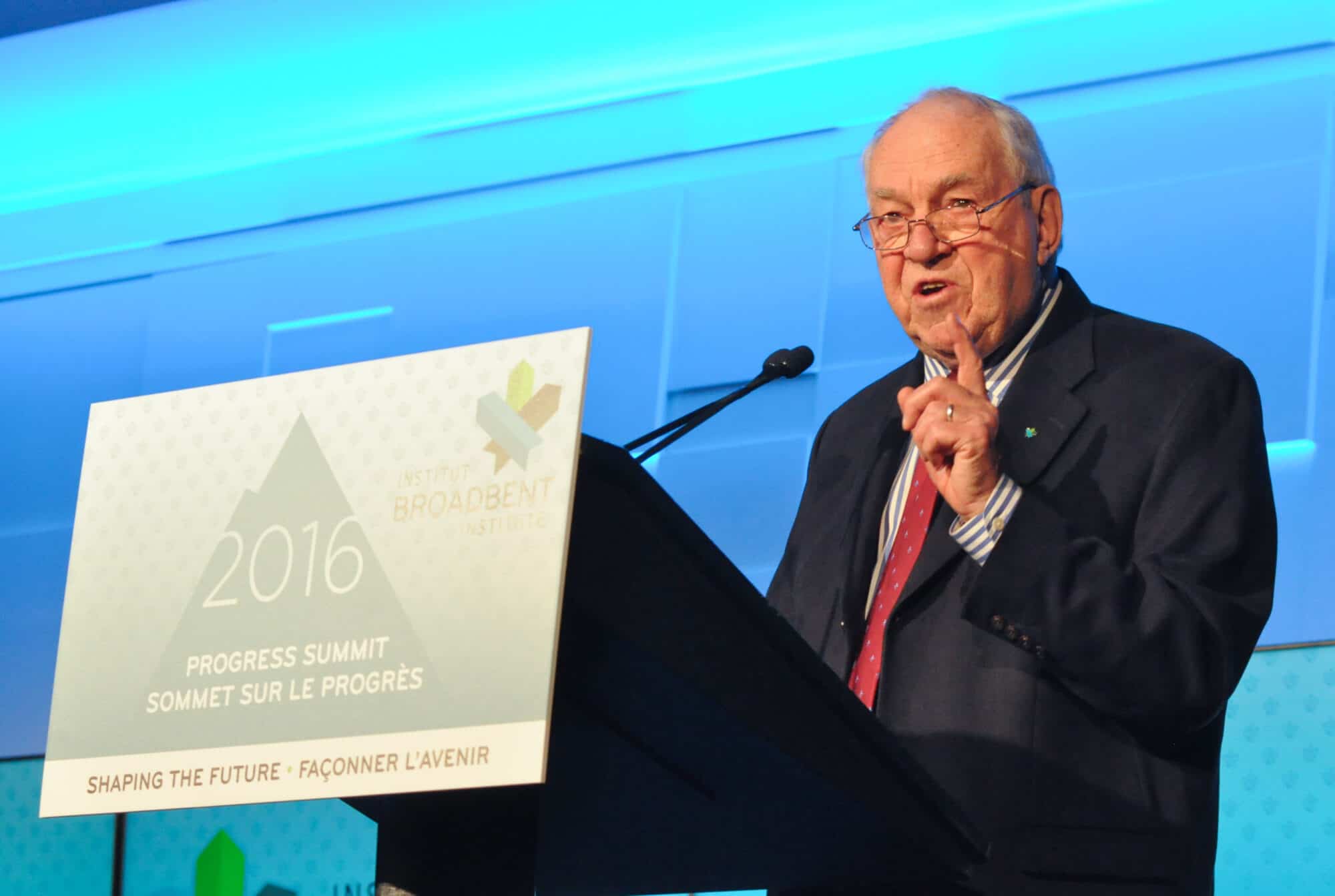

Ed Broadbent was awarded the 2016 Lifetime Achievement Award at Maclean’s Parliamentary of the Year Awards, held in Ottawa on November 15. His acceptance remarks reflect on a life in politics and the recent election of Donald Trump as President of the United States.

I want to thank Maclean’s for this award, for which I am deeply appreciative.

Let me begin my comments with a related story. The other day in downtown Ottawa, a man stopped me. Apparently he had heard something about this award.

“Mr. Broadbent,” he said, “while it’s true that you have some sort of reputation for civility, I must note that a number of other former MPs , Liberals and Conservatives, were very worthy. They were great debaters, cabinet ministers, even Prime Ministers. How is it that you received such an award and not they?”

I looked at him and said: “It’s simple. I outlived the bastards.”

One of the great benefits of being an MP is that you discover, beyond the comfortable confines of your own community and party, that other MPs from other parts of Canada have personalities and ideas that are not only different but also enrich your own personal and political life.

People like Monique Bégin, who was and is a thoughtful warm-hearted promoter of universal public health care. And Mauril Bélanger, whose premature and tragic death took place earlier this year, was a non-partisan democratic reformer.

I worked closely with him during 2004-2008 and witnessed up close a Minister who cherished Parliament, valued friendships, and listened to colleagues wherever they sat in the House of Commons. He is deeply missed by those who knew him.

I think also of Conservatives like the scholarly Gordon Fairweather, who was a passionate opponent of capital punishment and became Canada’s first Human Rights Commissioner.

Then there was the most underestimated leader in my lifetime: the Rt. Hon. Robert Stanfield.

Bob Stanfield had been the editor of the Harvard Law Review, and was in intelligence fully equal to the man who defeated him as Prime Minister. He excelled in compassion and in his understanding of Canada’s diverse regions and cultures. He had a great sense of humour.

A few days after the 1993 election which left two lonely Conservative MPs in the House of Commons, I ran into him on Elgin Street and expressed my sympathy. I still remember his answer. He looked me in the eye.

“Ed,” he said, “it got rid of a lot of riff raff.”

Elections can render unexpected outcomes and I’m sure that you, like I, are struggling with the question of where democratic politics go from here in the wake of the US election.

In the past few years I’ve been fortunate to spend my time divided between Canada and England. And within England, I divided my time between London, in the north-east and Devon in the west. Though the US election result exhibited particularly acute divisions along racial, gender and class lines, it does mirror some of the dynamics that I observed with the Brexit vote in the UK.

Yes, some of the disaffected yielded to the temptation to blame immigrants or far away Brussels – and some of the pro-Brexit campaigners were horribly and overtly racist.

But the large majority of Brexiters were just fed up with the elites of both major parties who had brought them deepening inequality.

Last Tuesday in the US a dangerous, shallow but skillful con man on the right won the election for a number of reasons; including his ability to speak to and about millions of his countrymen who like so many Englishmen had come to feel at best ignored and at worst disenfranchised.

I think particularly of white working-class families in Michigan, Pennsylvania, Ohio and Wisconsin, the states that provided his path to victory. These states are full of communities very much like my hometown of Oshawa.

The question to be answered is why Trump’s anti-elite rhetoric, even with its associated racism and misogyny, struck a psychological chord amongst so many blue-collar families in these once strongly Democratic states.

In good measure it was because the Democrats themselves had become associated with the unfair trade deals, the deregulation of Wall Street and devastated manufacturing communities. It was left to an authoritarian billionaire populist to talk about a “rigged system,” “destroyed jobs,” and a “working class” betrayed.

Yes, an alarming anti-pluralist populism has emerged in two of the world’s oldest democracies. Those elites whose policies and indifference helped lay its foundations must stop blaming its victims and re-focus their attention. They must turn their energy and talents to finding ways to reduce the deep anxieties of so many of their citizens.

Keynes warned us that the major obstacle to progress was the persistent strength of a bad idea. If a blind faith in unfettered markets continues to prevail, I believe the social foundation for our democracies will continue to be shaken.

As my Anglican Minister used to say on Sunday morning: Here endeth the lesson.

Thank you for this honour and thank you for listening.