Along with the price of keeping a roof over your head or filling up the tank for your car, the price of groceries keeps climbing. Meanwhile, grocery store executives and their shareholders take in record profits when grocery workers say they ‘can’t afford to shop’ at the stores they’re employed by. As food bank use rises and ordinary Canadians get squeezed, we need to take a good look at this glaring contradiction.

A new report from the Broadbent Institute entitled Canadian Grocery Profitability: Inflation, Wages and Financialization looks to understand how we got to this point and examines how the financialization of the grocery retail industry has raised prices while shrinking pay cheques. According to recent economic data, the current economic phenomena we’re faced with at the checkout aisle resembles a “seller’s inflation” scenario– to protect, and even enhance, their profit margins, corporations use economic shocks such as the pandemic and other global events to pass costs over to consumers through price inflation. The seller’s inflation phenomenon can also pass on costs to grocery store workers, denying them wage increases to meet the cost of living as evident in the real wage decline of grocery industry workers.

The House of Commons’ Agriculture Committee report on grocery affordability released earlier this summer notes that inflation has certainly been making food more expensive while grocery retail giants rake in extraordinary profits. There is recognition that these two trends of record profits and high prices are happening at the same time, but the committee’s report lacks an analysis of seller’s inflation while this framework becomes a useful tool for policymakers in the European Union to address the influence corporate profits are having on rising prices. The lack of acknowledgement of seller’s inflation in Canada’s grocery industry has lent to policy recommendations that may not be fully effective in pushing back against profiteering.

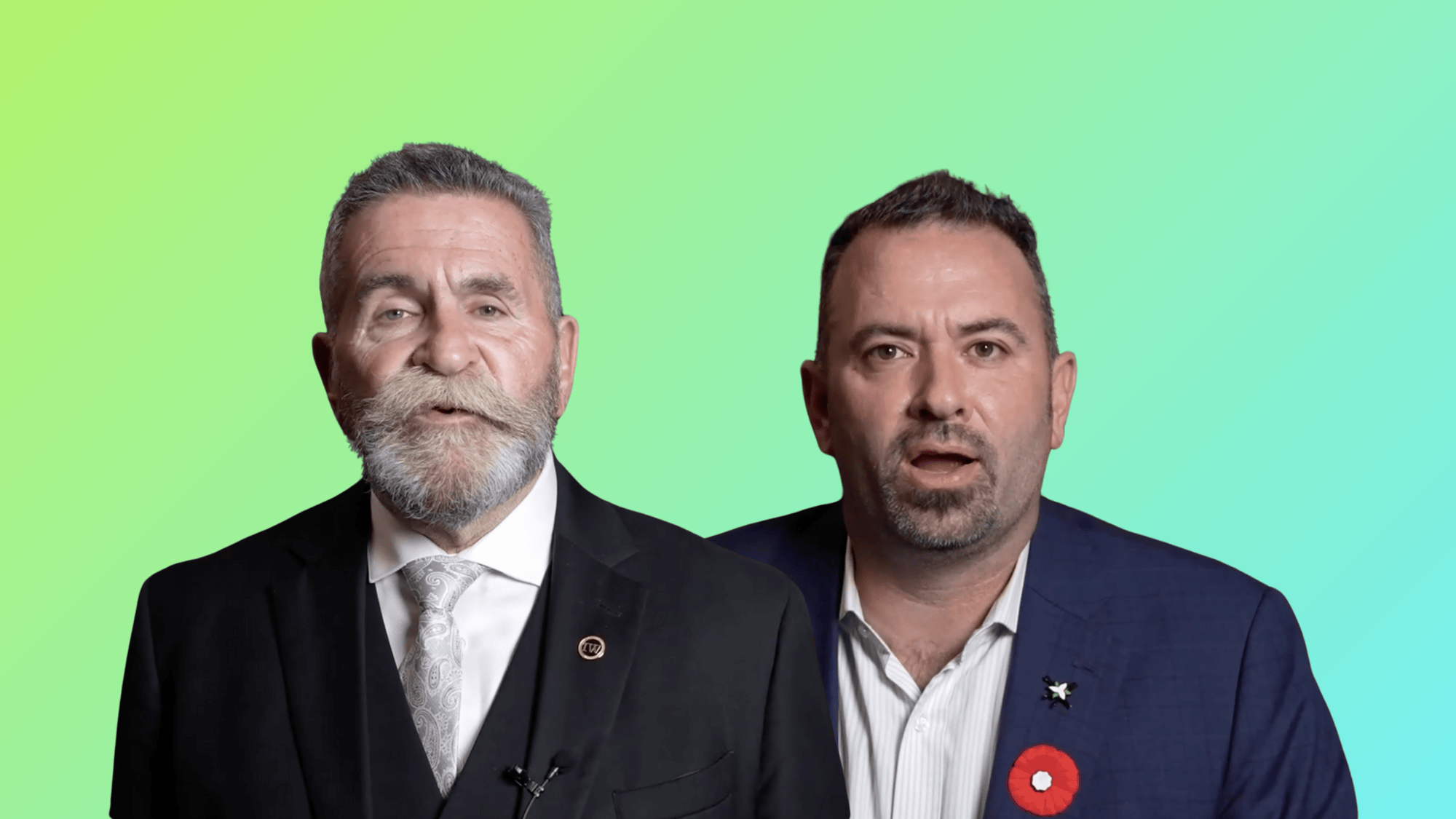

There’s also a noticeable lack of conversation on grocery and food system workers, who certainly do not see a cut out of these record revenues and have had to push back against corporate greed through their collective bargaining campaigns, such as the recent victory by Metro workers represented by Unifor.

Among the business executives, business association representatives, economists and academics consulted by the Agriculture committee, not one witness represented grocery workers. In the quest to maximize profits, corporate grocers do not intend to share their haul with the people who stock their shelves, scan their produce and effectively act as sheriffs outside of their job descriptions, over their merchandise.

The narrative over Canada’s grocery store profits has missed the working-class that work in these stores and warehouses, despite the major noise they’ve been making to push back against financialized interests. With major stakeholders in Canada’s extremely concentrated grocery retail market coming from financial investment firms like Blackrock and Vanguard, it should be no wonder that profits come first before the well-being of “essential workers” and ordinary Canadians struggling with the cost of living.

While government policy prescriptions such as windfall taxes, price controls, fixing competition rules and even city-owned grocery stores such as those being proposed in Chicago to alleviate food insecurity can all complement fairer food prices for Canadians, so far it has been the working-class through unions holding strong at the negotiating table that have led the way. It is no use for policymakers to continue to ignore labour’s perspective when it comes to pushing back against corporate greed.