Editor’s Note: The subject matter in the article below pertains to sexual and gender-based violence.

Canada recently designated the month of May as Sexual Violence Prevention Month, but amid the Hockey Canada sexual assault trial, Canadian media continues to cover the careers of the accused while obscuring the facts about the case. After highlighting the various teams that the accused perpetrators have played for in most media coverage of the trial, just one article in the last month dedicated just one paragraph to detailing the alleged assault, followed by five paragraphs detailing the careers of each man accused of sexually assaulting a woman in 2018.

Canadian media outlets are often underfunded and under-resourced. Journalists are increasingly forced to cover issues and write articles with the goal of increasing online clicks for profit, rather than writing on issues for the public interest. The existing digital ecosystem profits from sensationalist coverage—encouraging outlets to dismiss the needs of democratic accountability, and to instead focus on increasing readership.

This issue is especially harmful regarding media coverage on sexual violence. Studies suggest that the media plays a major role in shaping public perceptions of victims of sexual violence, and that the prevailing media environment model typically harms those seeking justice. While Canadian researchers have developed guidelines and practices for media outlets to reduce harmful reporting on sexual violence, today’s coverage continues to perpetuate harm.

Good Reporting is Out There

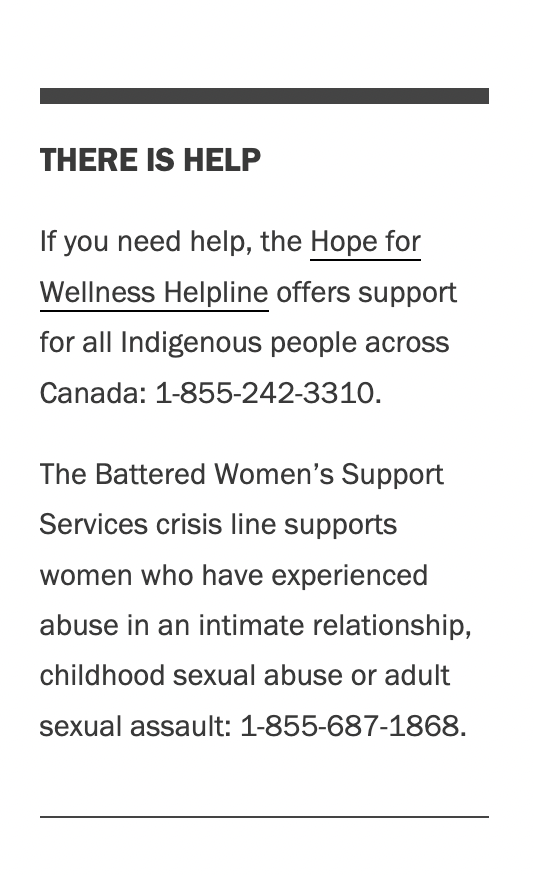

To their credit, certain outlets have done better reporting on sexual violence, raising public awareness and contextualizing such violence not as isolated incidents, but as a wide-reaching systemic issue. The Tyee, an independent, reader-funded outlet (which, as a disclaimer, I have written for) regularly provides coverage on sexual violence and gender-based violence written by those with frontline and lived experience. In an article from January 2025, The Tyee published an account by Angela Marie MacDougall, the executive director of Battered Women’s Support Services Association in Vancouver that drew attention to intimate partner violence as a public health issue. In another article, The Tyee reported on the inauguration of the Salal Sexual Violence Support Centre, interviewing various experts and highlighting the trauma-informed design of the centre to foster care and consent.

When covering gender-based violence and sexual violence, The Tyee often includes an editor’s note serving as a content warning, as well as sidebars including resources for those impacted by the issues being reported on. In these practices, the publication’s editorial team actively minimizes harm to survivors of sexual and gender-based violence among their readership—a well-reasoned consideration given that roughly 30 percent of women in Canada have experienced sexual assault.

This exemplary reporting—which draws on a number of expert opinions—contextualizes sexual violence as a systemic issue and minimizes potential harm to readers, offering a look at what higher-caliber reporting on sexual violence can look like. It is possible, and is actively being done by a Canadian independent news outlet. Mainstream coverage of sexual violence, however, falls far from this baseline.

The Coverage that Needs Work

The National Post, the flagship publication of the American-owned Postmedia Network, does not consider harm reduction in its coverage. Despite countless articles tagged with ‘sexual assault’ as a keyword, National Post coverage typically regards each instance of violence it reports on as a unique, standalone issue. Little expert commentary is available regarding the systemic nature of such violence, and most articles on the topic of sexual assault fail to contextualize such assaults as reflections of broader norms around rape culture, consent, misogyny, and bodily autonomy.

Where articles do note that such violence is not simply isolated, but part of broader trends around increasing gender-based violence, it is typically because the perpetrators of that violence happen to align with their political views of who ought to be persecuted instead. Recent coverage from Postmedia outlets on sexual violence focus on perceived legal lenience on violent offenders, as well as Canada’s immigration policy arguing for the deportation of newcomers that commit sexual violence. The reporting is often sensationalist, with commentary by experts, survivors, and frontline workers highly limited. Meanwhile, other perpetrators of sexual violence, like those on elite hockey teams, do not receive the same treatment.

There is also the issue of mainstream outlets’ reliance on police department media reports as the sole source to their reporting. This is a practice that is criticized for its reliability in reporting, and has certainly been used as a shortcut that does not provide accurate reporting. Police departments benefit from the public perception that crime, particularly violent crime such as sexual assault, is both pervasive and requires a police-based response. Police departments want to emphasize why police are important, and publications based on for-profit models that need to sensationalize crime can build mutually reinforcing relations with the police.

Media Influences Policy

Responding to this mainstream reporting in the recent 2025 federal election, Pierre Poilievre and the Conservative Party of Canada launched policies responding to high-profile coverage of intimate partner violence across Canada. They promised tougher sentences for abusers, stricter bail conditions, and a guaranteed first-degree murder charge for those who have killed their intimate partner.The platform focused on alleged “soft-on-crime, catch-and-release laws” that the Conservative Party and their supporters saw as the reasons behind intimate partner violence.

Despite these tough-on-crime policies, there was no support for women’s shelters, which have desperately called for increased funding due to increased need. If a woman was killed by her partner, Poilievre had a policy. If a woman wanted to leave the person harming her, there was nothing. Similarly, the Conservative Party’s platform lacked policies addressing the root causes of such violence, such as poverty reduction, or policies that focused on violence prevention.

A recent article in The Conversation effectively summed up the ineffectiveness of these policies: “Calling the police after a beating, rape or femicide does not prevent the crime from taking place.” Most news coverage of sexual violence, as well as on intimate partner violence, occurs after-the-fact. However, the most critical work around sexual violence focuses not on responding to violence, but on preventing it entirely. There is clearly a crisis of gender-based violence in Alberta, for instance, which has experienced a number of recent high-profile intimate partner violence killings. But while the violence has made the news, little reporting has covered the violence-prevention initiatives underway, and the clearly inadequate resources being afforded to these projects.

The Calgary-based initiative, “Shift: The project to end domestic violence,” runs the ConnectED Parents Project which works to build parents’ skills to support healthy youth relationships. Shift is also currently spearheading groundbreaking research in the Canadian context that explores the trajectories of domestic violence perpetrators to identify and break patterns that lead to domestic violence.

Alberta is also home to many different Next Gen Men initiatives, working with boys and men to reduce toxic masculinity that perpetuates gender-based violence. Across the province, sexual assault centres such as SACE (Sexual Assault Centre of Edmonton) provide essential counselling and support to survivors of sexual violence, as well as community education workshops and programming aimed at preventing sexual violence entirely. Alberta, so often in the news for gender-based violence, is home to many prevention-oriented projects and nonprofits. Yet, coverage of gender-based violence only highlights individual devastation and brutality, ignoring the systemic context and the opportunity to elevate preventative solutions. But violence sells headlines; preventing violence does not.

The Stories We Don’t Tell

Reviewing coverage of sexual violence cases and instances of gender-based violence, it also struck me that coverage focused on either highly sensationalist, ultra-violent cases, or on cases of women that look like me. I write from the positionality of a white settler, a cis-gender woman living in an urban centre. While gender-based violence disproportionately impacts women and girls, the Government of Canada identifies Indigenous, racialized, and 2SLGBTQI+ women and girls as statistically more likely to experience gender-based violence and sexual violence.

The stories we tell shape the world we live in. When media coverage fails to contextualize violence, to thoroughly examine its sources, to uplift the voices that most need to be heard, or to treat survivors with dignity and an intersectional lens, it reinforces the very systems that allow violence to persist. When searching landfills for the remains of victims of sexual violence becomes an election issue, when the depravity experienced by so many Indigenous women and girls remains a crisis, media coverage continues to miss the mark.

May is Sexual Violence Prevention Month, yet victims of sexual and gender-based violence still cannot find justice in their stories told by the Canadian media. While rooted in broader systemic issues, the media plays a role in perpetuating sexual violence, but it has the potential to play a role in its prevention. We live by the stories we tell, and we have every right to demand that those stories be told with care, accuracy, and justice.