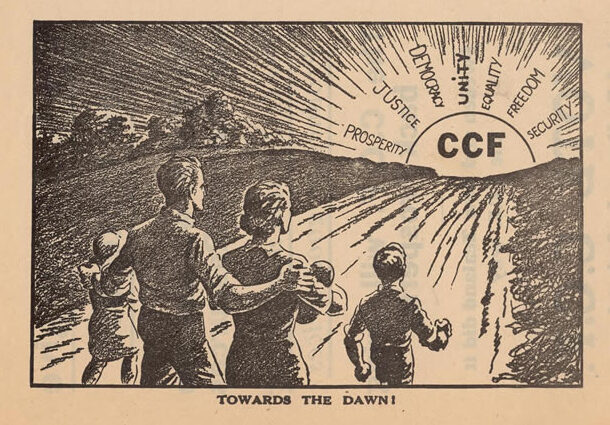

This special edition of Perspectives Journal poses the question: “Canadian social democracy at a crossroads?” This framing suggests only presently has Canadian social democracy arrived at such a fork in the road. Yet the history of other social democratic parties in the Global North, including that of the CCF-NDP, points to other periods where other forks in the road appeared, and consequential political choices made. In the late 19th and early 20th centuries, socialist and labour parties were established around the world with the goal of the socialist transformation of society. Throughout the latter 20th century, this transformative vision largely disappeared. Social democratic political parties that survived during this period no longer sought the whole transformation of society and instead pursued a pragmatic management of capitalism. The consequence for social democracy, in changing its pursuits, has become the contemporary decline in working-class support, declining leadership and representation of people from working-class backgrounds, and the weakening of once firm relationships with trade unions. (Rennwald 2020, 3). The CCF-NDP historical experience is not unique among these global historical trends for social democracy.

Contemporary social democracy is not equipped to take up the first of these options without a fundamental re-foundation ideologically, programmatically, and organizationally. Is such a deep reinvention possible by Canadian social democrats?

Social democracy, as a political movement, made peace with capitalism. However, the economic and political context of the 2020s requires social democracy to abandon this unrelenting adaptation. The post-1945 so-called “Golden Age of Capitalism” – characterized by Keynesian economic policies, an expansive welfare state, a male breadwinner/female caregiver family model, sustained economic growth, and a high employment rate – ended by the late 1970s. The neoliberal capitalist counter-revolution has now been sustained for considerably longer, and with that, a transformation in the post-1945 regime of labour-capital compromises. The contemporary ruling-class, both within the state and among the corporate elite, have seen no need to negotiate with the working-class. Consequently, we have arrived in an era of obscene and accelerating economic inequality, aggressive militarization, a climate crisis to which there has been no meaningful response, the normalization of austerity and welfare state retrenchment, and a far-right authoritarian populism which is on the march. The fork in the road for social democracy today is, on the one hand, to pursue a deeply radical response to the contemporary poly-crises, or, on the other hand, to continue to allow a pathological neoliberal capitalism to proceed unchallenged. Contemporary social democracy is not equipped to take up the first of these options without a fundamental re-foundation ideologically, programmatically, and organizationally. Is such a deep reinvention possible by Canadian social democrats?

The contemporary federal NDP is like other social democratic parties of the Global North in terms of its programmatic and ideological trajectory. This also holds true with respect to its relationship to the working-class. This is to say, since the late 19th century, social democracy was anchored in the working-class through party membership, electoral support, and the trade unions. Since the neoliberal turn in the 1990s, this organic link has thinned and rather seriously so. What is critical is the transformation in social democratic epistemology or put another way, how social democrats understand the state and economy to inform governance practice and public policy. Across the Global North, Social democracy has demonstrated a capacity to adapt to the variants of capitalism. This flexibility has led to a characterization of social democracy as, “not a fixed doctrine but a political movement, as protean as the capitalist economy” (Gamble & Wright 1999, 2).

As visions for political and economic transformation vanished as social democratic parties matured during the general turn to neoliberalism, their adaptation to the ebbs and flows of capitalism normalized. Governmental power, the sine qua non of social democracy, failed to factor in the specific structural relations the state embodied within its apparatus: the state in a capitalist society is a capitalist state, and for social democrats in government this point is often lost. The state, as constructed in the capitalist context, is not a neutral machine to be steered in whichever direction; its apparatus and function is tied to specific class interests. This had implications for the policy and practice of social democracy by the 1960s, where constraining private ownership over the means of production was de-emphasized. Socialism, as a goal, was then replaced by the objective of technocratic regulation of capitalism (Bailey 2009, 30). Obviously, there were serious forces at play such as the liberalization of trade and investment, otherwise known as “globalization,” the disorganization of the working-class as precarity increased and union density declined, as well as capital’s mobilization to weaken the democratic state and workers’ bargaining power, but social democracy, having shed a class perspective, did not seek to resist. At this point, social democracy was no longer concerned with articulating an anti-capitalist vision and mobilizing the working-class for an alternative.

As the neoliberal project restructured capitalism and the state, social democracy had no logical response but to align and integrate with these forces after abandoning its raison d’être. The stagflation crisis of the 1970s set in motion a process which would ultimately deprive social democracy of the economic basis to continue the project of welfare state expansion. Business, under real economic stress from the mixture of high inflation, stagnant growth, and high unemployment, began to mobilize as growth in productivity rates slowed from an annualized global aggregate of 6.4 percent in the late 1960s to 3.4 percent for 1973-79. Meanwhile, as militant trade unions were able to win more at the bargaining table, business profit rates that peaked in 1968, then began to decline (Glyn, Hughes, Lipietz and Singh 1990, 76 and 83). The crisis of profitability signalled a general crisis of capitalism and of a paradigm shift, marking the conclusion of the post-1945 Golden Age of capitalism’s collusion with social democracy. As a result of new and serious constraints on the pursuit of socialist policies when in office, including the growing power of finance capital, by the end of the 1980s social democrats that were elected to power began to govern following the neoliberal playbook (Albo 2009, 119).

As neoliberalism became hegemonic through the 1980s, social democracy again transformed. Social democratic parties turned to a model of progressive competitiveness based on supply-side policies focused on training and skills formation, while simultaneously turning to public sector austerity (Merkel, Petring, Henkes and Egle 2008, 6 and 25). The power of government would not be deployed to redistribute resources, as previously designed under social democratic auspices, but rather to enable individual workers to compete in an increasingly polarized and precarious labour market. By the mid-1990s, social democracy had come to accept many of the tenets of neoliberalism (Crouch 2011, 162).

The 2008 Global Financial Crisis (GFC) should have been an opportunity for social democracy to realize its mistakes and re-connect with its wavering working-class and trade unions constituents. Instead, governing social democrats across the West turned to austerity. Public sector pay cuts and freezes, privatization of public assets, public pension cuts, sundry cuts to a range of social benefits, and regressive increases to the value added tax, constituted the program of social democracy in response to neoliberal capitalism’s existential crisis. One indicator of social democracy’s failure to respond to the crisis can be demonstrated by the 2009 “Amsterdam Process” – a series of discussions and publications regarding the ideological renewal of European social democracy, undertaken by social democratically aligned think tanks, the Policy Network (UK) and Wiardi Beckman Stichting, linked to the centre-left Dutch Labour Party. This reflection identified the problem where the, “financial crisis of 2008 … exposed an ideological vacuum in social democratic thinking” (Policy Network, The Amsterdam Process, n.d.). The conclusion, however, was not a refoundation of social democracy, but a confirmation of its existing modus operandi. Ultimately, the Amsterdam Process settled on accepting the need for further welfare state restructuring, increasing the retirement age, and the centrality of businesses interests in social democratic practice (Cramme, Diamond, Liddle, McTernan, Becker and Cuperus 2012, 17-25). What social democrats post-GFC offered was somewhat greater enthusiasm of their embrace of neoliberal capitalism.

What the Amsterdam Process illustrated here was indicative of the ideas and position of 21st century social democracy generally. It has arrived at a point where it is, even as capitalism presents its weaknesses, incapable of rising to the real challenges of the time. Given this impasse, what is to be done about contemporary social democracy? Looking to the Canadian context, a couple of key questions can guide this re-imagining: how can the federal NDP rebuild to become a vehicle for working-class politics and broader social transformation? What should the role of the party be in class formation; a process which transforms a collection of individuals, sharing similar economic contexts into a distinct agent with the capacity to resist and challenge the prevailing political and economic order, and in rekindling democratic socialism?

Obviously, Canada’s political party system differs from most countries in Western Europe and the United States. While iterations of a Canadian social democratic party faced different historical developmental trajectories than European parties, such as later development in the early 20th century compared to the 19th century genesis of socialist parties across the Atlantic, it does substantially exist in a North American context where none exist in the US. Additionally, the 2008 GFC was not as acutely catastrophic in Canada, as elsewhere in the European Union and US. Yet nearly a half-century of economic restructuring has dramatically transformed the structure of today’s economy and, with it, the class structure of Canadian society. For the NDP to become a vehicle for working-class electoral politics and broader social transformation, it would require a fundamental programmatic, organizational, and, indeed, cultural transformation away from what currently exits. Doing so would entail a process of broad democratic engagement with the party’s membership, trade unions, and social movements outside of electoral politics. Operationally, this would include the drafting and circulating of discussion papers on urgent issues such as climate, economic inequality, decommodification of housing, taxation, trade and investment, and Canada’s participation in NATO, to name a few. As the party is structured around the Electoral District Associations at the grassroots-level, they would be responsible for organizing constituency discussions of these documents. Concluding with collective positions on these issues, EDAs would go forward to party central to collate and prepare the ground for a refoundation conference.

For the NDP to take up the work of class formation, it would need to dramatically re-imagine its functions beyond electoralism, which would require a transformation of its present organizational structure.

As part of this process, the work of class formation must become a key component in the political repertoire of the party practice. Class formation entails a range of processes through which workers build a shared identity and awareness of political and economic interests based on their location within social and economic structures. Through these processes, individuals and the class more broadly come to recognize what they have in common and create strategies and means to act collectively. The work of class formation includes education programs; engagement in popular struggles such as strikes and political mobilizations; cultural programs and events where the images and stories of the working class are foregrounded; and mutual aid programs such as food co-ops and legal support for tenants and non-unionized workers. Ultimately, through such experiences, workers come to know which side they are on and, importantly, who is there with them. In this regard, class formation is a continuous process, and not a fixed point where the work stops upon arrival when it reaches a state of coherence and obtains power.

For the NDP to take up the work of class formation, it would need to dramatically re-imagine its functions beyond electoralism, which would require a transformation of its present organizational structure. EDAs would be supplement by party ‘clubs’ located in workplaces, neighbourhoods, schools, and other institutions in civil society. To be a member of such a party would entail more than frequent calls to ‘chip in’ with monetary contributions, without substantial engagement in its democratic functions. Instead, members would be called upon to actively participate in building the life of the party and engage with the work of class formation through study circles, campaigns, cultural events, and elections. With respect to elections and their contribution to class formation, electoral work would be framed as an opportunity for popular education on crucial issues, offering a critique of capitalism and the tremendous inequalities it necessarily creates, but also popular education on an alternative vision for society. This also means developing a clear vision of where the NDP wants to go, and how to get there.

If such a radical, explicitly anti-neoliberal – if not anti-capitalist – refoundation of social democracy were undertaken, it would not go unchallenged by capital. There have also been important changes in the class structure which demand consideration. This social transformation that has taken place under neoliberalism is particularly important to address with respect to undertaking the groundwork of class formation, as well as cross-class alliance building.

First and foremost, capital would respond aggressively as history has repeatedly demonstrated. In France, the Union of the Left government led by President Francois Mitterrand in the early 1980s implemented a program that included, among other actions, the nationalization of the banking industry and dramatic increases in the minimum wage. The response from capital was investment flight and rising unemployment. Soon after, Mitterrand’s government would abandon the stated objective of a ‘rupture with capitalism’ to reconcile with it. As in the 1970s, a transformative social democracy today would induce capital to deploy think tanks and the highly concentrated corporate media to shape the narrative and redefine the problem. To underestimate business mobilization would be fatal to a party that is programmatically committed to re-balancing class power in favour of a broadly defined working class. Countering such an inevitable response from business interests would require a party membership which fully understands the stakes and the field, and is networked into trade unions, schools, and neighbourhoods to mobilize people, ideas, and political analysis. This means more than a passive ‘chip in’ membership – the party must help members must study power relations and help them train for active participation in the full range of political venues.

Beyond business, the task of mobilizing around a radical program requires confronting deep changes in the class structure. Structural weaknesses that have developed under the weight and tenure of neoliberalism include the decline in private sector trade union density; the commensurate decline in the number of industrial workers; the growth in the number of service workers which are typically, in the private sector, non-union; and the expansion of a professional-managerial class in the broader public sector, whose material interests may coincide with a radical, anti-neoliberal program.

It is the time to rediscover the radical imagination that social democracy was founded on and begin the work of building a truly independent socialist party that meets the challenges of growing economic inequality, climate change, integration with the American economy and so much more.

In Canada, private sector union density has declined from 32.2 percent in 1970 to slightly above 15 percent today (Doorey and Stanford 2023). The decline in union density is, at least in part, responsible for stagnant real median wages for Canadian workers which have hardly grown since 1970s and have not kept up with inflation (Breznitz 2024). Overall, economic inequality has been accelerating. In 1970, the bottom 50 percent income of Canadians incomes held 22.59 percent of all income. By 2023, the bottom 50 percent’s share declined to 17.31 percent. In contrast, the top 1 percent of Canadians held 6.62 percent of all income, and by 2023 this had grown to 11.64 percent (World Inequality Database). These material conditions present an opportunity for a radical Left politics. As noted earlier, social democratic parties in government have largely alienated their working-class constituency. The political rebuilding here will take more than a call to “vote for us,” and requires building a party that has a presence in elected legislatures, as well as civil society, engaging in more than electioneering.

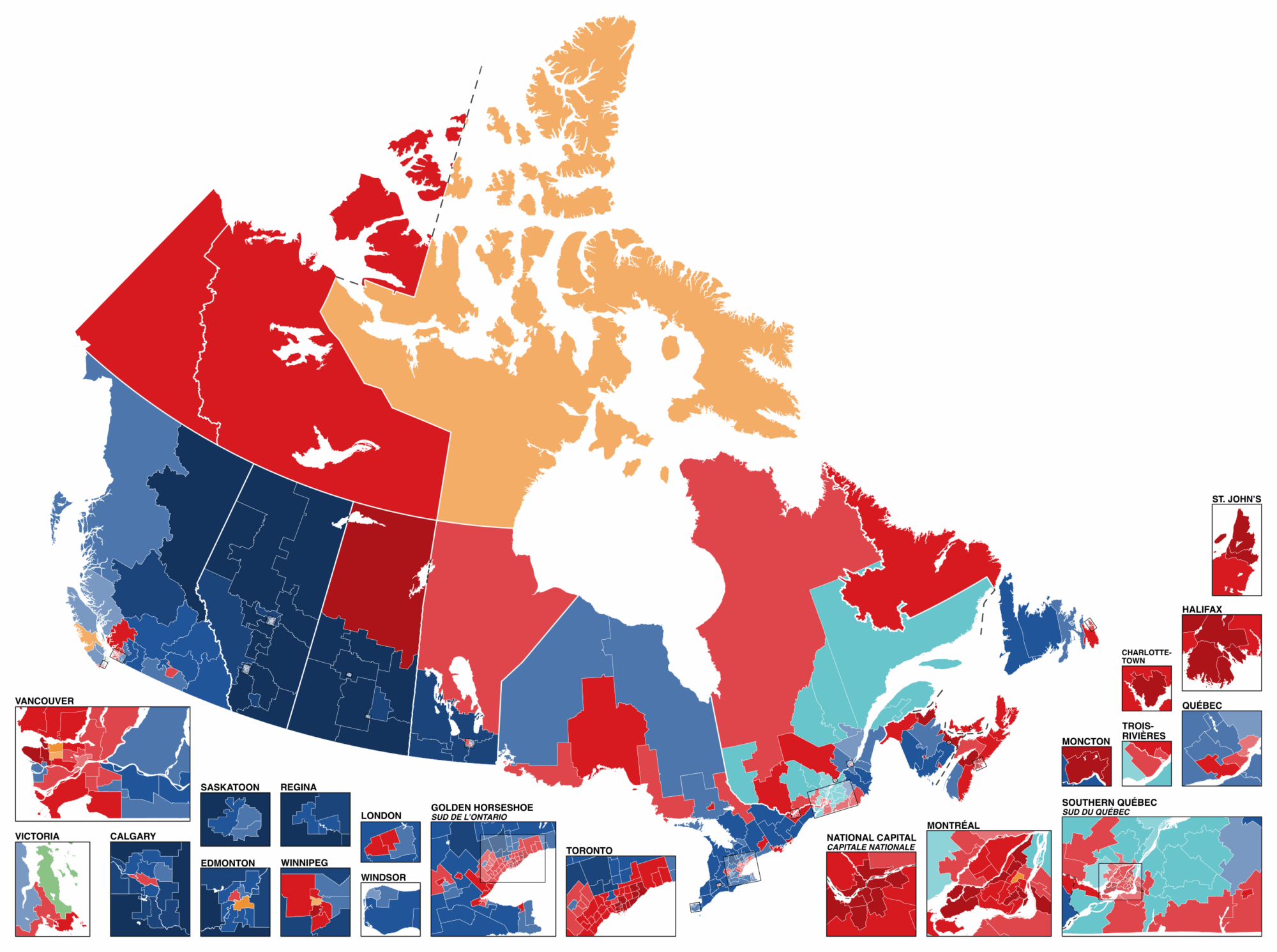

The broad developments within and around social democracy point to the necessity of a refoundation. The disastrous result of the 2025 federal election for the NDP presents an opportunity for a fundamental re-think. It is the time to rediscover the radical imagination that social democracy was founded on and begin the work of building a truly independent socialist party that meets the challenges of growing economic inequality, climate change, integration with the American economy and so much more. The democratization of the party structures and processes create the space for a potential rethink of strategy and public policy based upon democratic planning and public ownership. The well-worn and failed formulas of the neoliberal era must be abandoned if there is to be renewal.

References

Click to expand for a full list of references

Albo, Gregory. 2009. “The crisis of neoliberalism and the impasse of the union movement”, Development Dialogue (January), 119-131.

Bailey, David. 2009. The Political Economy of European Social Democracy. Routledge: Abingdon.

Breznitz, Dan. 2024. “How Canada’s Middle Class Got Shafted”, Globe and Mail, September 19 available at https://www.theglobeandmail.com/business/commentary/article-how-canadas-middle-class-got-shafted/

Brodie, Janine and Jane Jenson. 1988. Crisis, Challenge and Change: Party and Class in Canada Revisited. Ottawa: Carleton University Press.

Chibber, Vivek. 2025. “Materialism is Essential for Socialist Politics”, Jacobin, 20, May available at https://jacobin.com/2025/05/materialism-socialism-democracy-left-wing

Clark, Campbell. 2021. “The NDP is Strong on Tiktok but Weak on the Ground.” Globe and Mail, October 8.

Cooke, Murray. 2006. “The CCF-NDP: From Mass Party to Electoral-Professional Party.” Paper prepared for the annual meeting of the annual meetings of the Canadian Political Science Association, June 1-3.

Cramme, Olaf, Patrick Diamond, Roger Liddle, Michael McTernan, Frans Becker and Rene Cuperus. 2012. A Centre Left Project for New Times. London: Policy Network.

Crouch, Colin.2011. The Strange Non-Death of Neoliberalism. Cambridge UK: Policy Press.

Doorey, David and Jim Stanford. 2023. “Union Coverage and Inequality in Canada”, Centre for Future Work, available at https://centreforfuturework.ca/2023/10/19/union-coverage-and-inequality-in-canada/

Fagerholm, Andreas. 2013. “Towars a Lighter Shade of Red? Social Democratic Parties and the Rise of Neo-liberalism in Western Europe, 1970 – 1999”, Perspectives on European Politics and Society, accessed August 26 2013 at http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/15705854.2013.772748

Gamble, Andrew and Tony Wright (eds.).1999. The New Social Democracy, Oxford: Blackwell.

Glyn, Andrew, Alan Hughes, Alain Lipietz, and Ajit Singh. 1990. “The Rise and Fall of the Golden Age”, in Stephen Margin and Juliet Schor, editors, The Golden Age of Capitalism: Reinterpreting the Postwar Experience, Oxford: Clarendon Press.

Hall, S. (1986). “The Problem of Ideology-Marxism without Guarantees”. Journal of Communication Inquiry, 10(2), 28-44. https://doi.org/10.1177/019685998601000203 (Original work published 1986)

Kitschelt, Herbert.1994. The Transformation of European Social Democracy, Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press.

Lukacs, Martin. 2025. “How Pierre Poilievre’s Conservatives Seduced Working Class Voters.” The Breach, May 4

McGrane, David. 2019. The New NDP: Moderation, Modernization and Political Marketing. Vancouver: UBC Press..

Merkel, Wolfgang, Alexander Petring, Christian Henkes, and Christoph Egle. 2008. Social Democracy in Power: The Capacity to Reform. London and New York: Routledge.

Moschonas, Gerassimos. 2002. In the Name of Social Democracy: The Great Transformation, 1945 to the Present. London: Verso.

Parker, Jeffrey and Laura Stephenson. 2008. “Who Supports the NDP?” Paper prepared for presentation at the annual meeting of the Canadian Political Science Association, Vancouver, June 4-6.

Policy Network. n.d. “The Amsterdam Process”, accessed 5 October 2013 at www.policy-network.net/content/369/The-Amsterdam-Process

Polacko, Matthew, Simon Kiss and Peter Graefe. 2025. “The Long and Short View of Working Class Voting in Canada,” in Jacob Robbins-Kanter, Royce Koop and Daniel Troup, editors, The Working Class and Politics in Canada. Vancouver: UBC Press.

Westlake, Daniel. 2025. “Electoral Coalitions and the Working Class: The Case of the Liberal Party,” in Jacob Robbins-Kanter, Royce Koop and Daniel Troup, editors, The Working Class and Politics in Canada. Vancouver: UBC Press.

Whitehorn, Alan. 1992. Canadian Socialism: Essays on the CCF-NDP. Toronto: Oxford University Press.

World Inequality Database available at https://wid.world/country/canada/