The Harry Kitchen Lecture in Public Policy was delivered by the Broadbent Institute’s Andrew Jackson, on April 8, 2015 to the Department of Economics at Trent University.

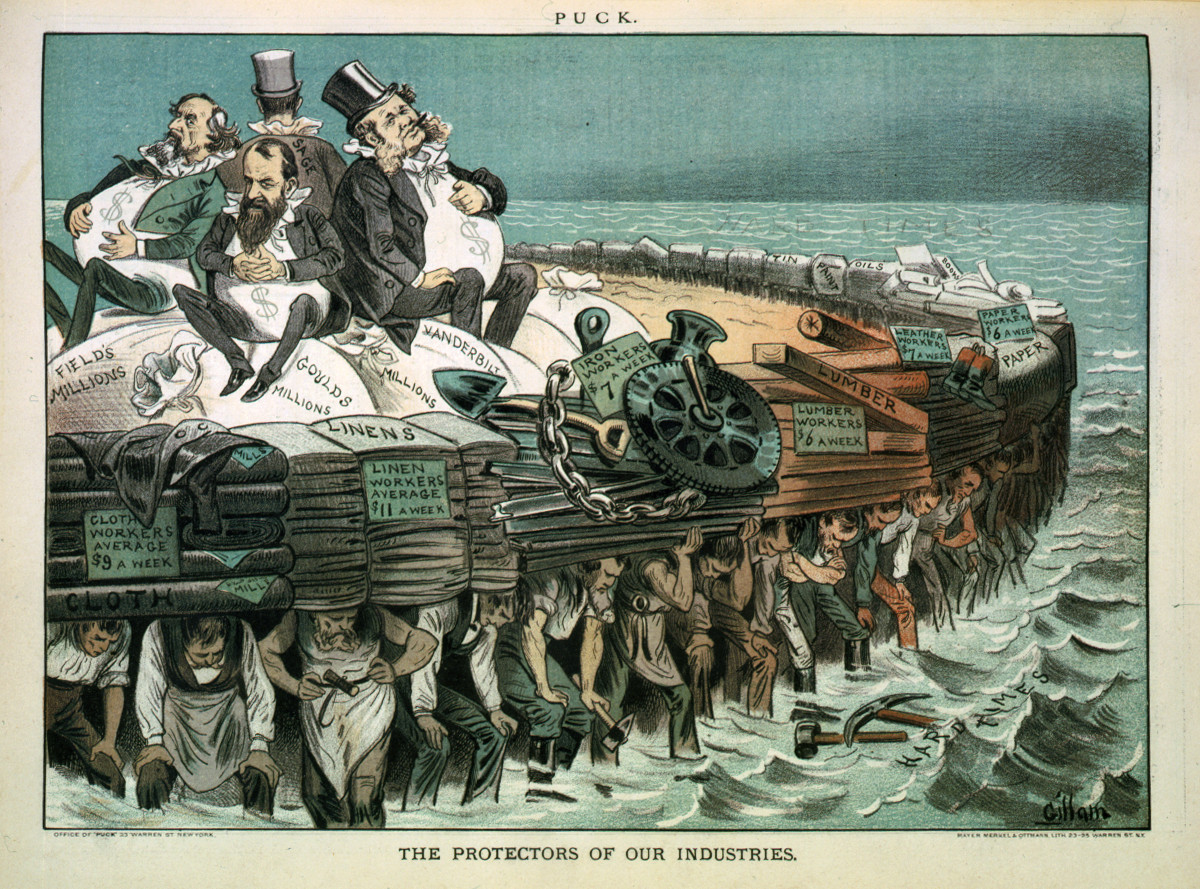

In recent years, more and more attention has been paid to rapidly rising income and wealth inequality in advanced economies, including Canada. My focus here is on economic or class inequality and I ignore other important sources of inequality based on race, gender and Aboriginal status. The major focus has been the increased concentration of income and wealth in the hands of a small elite. On the eve of the most recent Davos summit of the global super rich, Oxfam drew attention to the striking fact that almost as much of the world’s wealth is now owned by the top 1% as by the bottom 99%. A recent study finds that the top 0.1% in the United States, that is one person in a thousand, now own 22% of all US wealth, up from 7% in 1978.

Thomas Piketty’s recent best-selling book, Capital in the Twenty First Century (2014), argues that we are on the eve of a new Gilded Age of highly concentrated wealth and inherited privilege. He meticulously documents wealth and income shares in the advanced economies from the Victorian era, showing above all that a period of equalization beginning in the post War period – what Paul Krugman (2000) has called the “Great Compression” – went into reverse from the early 1980s.

While Canada falls well short of US levels of inequality, the OECD notes that we have become much a more unequal since the early 1980s. Today, the top 10% own almost half of all wealth. According to the latest rankings, for 2013, the top 100 Canadians now collectively have a net worth of $230 Billion. This elite group are all worth more than $728 million, and will likely soon consist entirely of billionaires. The Thomson family tops the list at over $26 billion, and 38 Canadians have more than $2 billion in net assets. In many cases these fortunes have been inherited.

Looking at income, the top 1% of Canadians now receive 12% of all taxable income, up sharply from 7% in the early 1980s (CANSIM Table 204-0001). Over one half of all taxable income from capital gains goes to taxpayers earning more than $250,000 per year.

Why, it is often asked, does this concentration of wealth and income at the very top matter? Part of the answer is that the rapid growth of top incomes has taken place against the backdrop of stagnant middle-class living standards. Canadian real GDP per person grew by 50% from 1981 to 2011, but the real median hourly wage (half earn more and half earn less) rose by just 10% over this extended period. Rising tides boosting the fortunes of the rich have left far too many boats stuck in the mud.

The more important answer is that too much inequality undermines a healthy society and meaningful equality of opportunity for all individuals to develop their talents and capacities to their fullest. Canadians might not endorse equality of condition, but they certainly believe that all children should have a fair chance in life. Research by Miles Corak (2013) has shown that the life chances of children are much less determined by the economic circumstances of their parents in more equal societies like Sweden compared to more unequal societies like the United States, with Canada standing somewhere in between.

In all societies, economic inequality underlies important differences in well-being, such as life expectancy. Here in Canada, 65% of men at age 25 will live to age 75, but that varies a lot from 51% for men in the lowest income decile, to 75% for those in the

highest income decile. The key point here is that those in the middle do worse than those at the top, so reduced life expectancy is not just a function of poverty. Inequality – a person’s relative position in the social hierarchy – matters too.

Similarly, literacy and numeracy levels of young adults vary by the families rank in the economic hierarchy. These differences are greater in more unequal societies. That is why, as Wilkinson and Pickett (2009) have shown, more equal societies do significantly better with respect to a range of widely valued outcomes, including health status, low levels of crime, high levels of trust, and so on. It can be added that large inequalities in economic resources can also subvert democracy, especially in countries which do not limit the role of money in politics. (Hacker and Pierson, 2010.)

Economic inequality is, of course, functional to a degree. In a market society, we expect rewards to differ based upon effort and application (though rewards to talent alone are morally more problematic). Incentives are important, (though not all incentives need take a monetary form.) However, the idea of a major trade-off between equality and economic efficiency, a commonplace of textbook Economics 101, founders on the fact that at least some relatively equal advanced industrial countries have performed relatively well in economic terms – think here of Germany and Northern Europe compared to the United States and Canada. And it is not at all true that advanced industrialized countries as a whole have performed better in terms of growth and productivity in the age of rising inequality than they did in the Golden Age era of shrinking inequality from the 1940s until the economic crisis of the 1970s.

A common argument for being relaxed about inequality is the concept of just desserts. The rich, we are told, deserve to be rich because their reward is equal to their disproportionate contribution to the net social product. Economists tend to think that wages approximate to marginal productivity, and that profits and returns to capital reward astute investment and risk-taking. This is true to a degree. Steve Jobs made a fortune because he inspired a team of very talented people who designed fantastic products that consumers were desperate to buy. But this ignores a host of factors. As Mariana Mazzucato (2014) has shown, all of the key technologies embodied in iconic Apple products like the iPhone were developed at public expense and essentially given away. Apple received government start-up assistance. Apple has profited hugely from outsourcing production to ultra cheap labour in China through contractors like Foxconn, and exercises market power by forcing consumers to play in a walled garden. It is absurd to attribute value added to any single individual, no matter how talented, given the huge complexity and inter-connectedness of social production as a whole.

Economists also tend to ignore power in favour of highly stylized models of the competitive so-called free market. Yet, as Joseph Stiglitz argues in his book The Price of Inequality (2012) , a great deal of wealth is built on the basis of power in the marketplace, from the high profits of drug companies based upon patents, to the above average returns of monopolies and oligopolies. Consider that iconic new economy companies such as Google and Amazon have made billions for their owners by establishing dominant positions in “winner take all” markets. And, critically, CEOs and senior executives – a major chunk of the global rich and the top 0.1% – have exploited their position as insiders to boost their incomes, as opposed to becoming markedly more productive. Canadian CEOs in 2013 earned 189 times the average wage, up from 105 times in 1998.

As former dean of the Rotman Business School Roger Martin argues, a big reason for this surge in relative pay has been the shift to stock-based compensation. Timely cashing in of stock options can deliver huge gains from events over which senior managers have little or no control. For example, Bill Doyle CEO of Potash Corp made a fortune from his stock options when the price of potash soared. Financial insiders have reaped huge rewards from destructive and often illegal speculation and insider dealing, and it is at least an open question if some financial products developed in recent years have any real productive function at all.

Another key dimension of power is the bargaining power of capital compared to labour in the job market. Labour generally has less power because of slack in the job market, and because wage income is the basis of economic well-being. One notable trend coinciding with the increased concentration of wealth has been a generalized rise in the profit share of national income as opposed to the wage share. This matters because income from capital is much more unequally distributed than income from labour.

The trend to a falling wage share is bound up with factors such as technological change and globalization, and also with the steady erosion of unionization in the private sector of the economy, above all in the United States where just 7% of such workers now belong to unions.

I turn now to the question of why economic inequality has increased in what might be termed the age of neo-liberalism that began with the Reagan/Thatcher revolution of the late 1970s and early 1980s. This in turn sets the stage for a brief discussion of how we should respond.

One way to think about this, following Marx and Piketty, is to see mounting inequality as inherent in a capitalist economy marked by concentrated private ownership of the means of production and the existence of a labour market in which workers normally have less bargaining power than capital. One (crude) reading of Marx is that he foresaw the concentration of capital in ever fewer hands, combined with mounting immiseration of labour. Piketty argues in a similar vein that wealth tends to rise relative to income, and that the rate of return on capital normally exceeds the rate of economic growth (r > g). This leads to the accumulation of wealth in the hands of the few over time, even if wages rise in line with growth.

As has been widely noted by James Galbraith and Jospeh Stiglitz among others, Piketty fails to distinguish between wealth and capital considered as a factor of production. Wealth includes assets such as housing and works of art that are not factors of production, and wealth is also significantly affected by the valuation of capital assets by financial markets. A stock market bubble boosts the value of capital assets of companies and their owners, but does not increase the productive potential of the economy per se.

Conventional neo-classical economists and most Marxists alike would argue that returns to capital as a factor of production cannot rise inexorably, and will fall as capital becomes more abundant. This can be seen in a micro economic sense in any specific industry, such as the global auto industry. If too much capital is invested in the sector, overcapacity will develop and prices and profits will fall. Arguably, this is precisely the case today in many industries.

In a similar vein, it can be argued that there are limits to the extent to which the capital share of national income can increase without undermining profitability due to the stagnation of markets. If wages stagnate or fall, the ability of most households to consume will be clearly limited – at least in the absence of abundant credit to paper over the cracks. The holders of wealth may consume, sometimes to excess, but they are unlikely to consume the same share of their income as the great mass of the population. This will give rise to the surplus savings problem identified by Keynes.

The key point is that the over-accumulation of capital is inherently limited, and sets the stage for economic crisis. If the productive capacity of the economy outstrips the growth of demand, profits and investment will fall, and unemployment will rise. Over accumulation and under consumption are one widely accepted explanation of the Great Depression of the 1930s, and arguably underpin today’s problem of very slow global growth.

Contrast this situation with how a healthy capitalist economy should function. Growth should be led by investment, mainly business investment. Credit financing of investment increases demand in the economy, while also raising productivity. Private investment is critical to growth not just because it deepens the physical capital stock, but also because it drives technological and organizational progress, what economists like to call total factor productivity. Higher productivity – the increase in our collective capacity to produce more per hour of labour – sets the stage for higher wages, and higher levels of consumer spending. This increase in demand fuels further rounds of investment. Seen from this perspective, too much inequality is a major problem if it results in the suppression of wages, or too much saving relative to new opportunities for profitable investment.

Recently, researchers with such august economic bodies as the IMF the OECD and, especially, the ILO, have begun to argue that too much inequality is, in fact, bad for the health of capitalism. The problem of insufficient global demand due to the generalized lagging of wages behind productivity growth over the past twenty years was temporarily papered over by growing household debt, especially in the US. This has also been seen in Canada where mortgage debt and a housing bubble have been a major driver of growth since 2000. The growth in household debt was financed in significant part by the surplus savings of corporations and the affluent, part of what came to be known as the global savings glut. Business investment globally has meanwhile been weak, partly due to the modest capital requirements of the new digital economy.

Many prominent economists such as Stiglitz, former US Secretary of the Treasury Larry Summers and the International Monetary Fund chief economist Olivier Blanchard argue that mounting inequality has been a significant factor behind “secular stagnation”, an extended period of very slow growth as surplus profits and savings sit largely idle while households seek to reduce their debts. (To digress for a moment, the problem is greatly compounded if governments impose austerity rather than pick up the slack though increased public investment, as Keynes would have counselled.)

To return to the causes of rising inequality, the rise in the fortunes of the rich was the result and in part the intended consequence of the deliberate dismantling of what might

be termed the “managed capitalism” of the post-War era. Full employment was largely abandoned as a key goal of macro-economic policy, leading to disinflation via the recreation of a “reserve army” of the unemployed and the precariously employed. The financial sector was deregulated, creating a new space for profit making and increasing the pressures on the rest of the economy to maximize short-term profits. Unions and minimum employment standards were deliberately weakened, decreasing the wage share and also lowering the relative wages of unskilled and semi-skilled workers.

Globalization shifted many middle class manufacturing jobs and, increasingly, service jobs to low wage countries, and contributed to downward pressures generally on wages. Changes to social programs such as unemployment insurance and social assistance also worked against the bargaining power of labour. The shift back to the market has also had important cultural consequences.

Technological and organizational change has also been a major part of the story. To some degree it and globalization have worked hand in hand to eliminate traditional middle class jobs. So called skill-biased technological change has increased the proportion of good, well paid jobs requiring advanced education, but not by enough to compensate fully for the loss of middle-class jobs. Competition for low pay, relatively low-skill jobs not vulnerable to replacement by machines or to off shoring has increased, leading to a sharply polarized job market as emphasized by David Autor of MIT. These pressures are likely to intensify in what has been called “The Second Machine Age” as advanced robotics, Artificial Intelligence, “the internet of things” and a host of new innovations enabled by exponential increases in computing power displace labour.

Many observers such as Guy Standing see the future labour market as made up a growing “precariat” , a shrinking but still not insignificant middle class struggling to maintain living standards, and a top third or so who are doing well. Within the top third of managers and professionals, those at the very top, especially the top 0.1%, will likely continue to pull away from the rest of us. At the apex sit the global super rich, including the executive cadres of large global corporations, the titans of global finance, super stars and the lucky few who have inherited wealth. Some see even the top third as threatened by winner take all markets and by continuing technological charge.

One point worth emphasizing is that extreme inequality has been mainly driven by trends in the job market and by the rising capital share of income. It is mainly an issue of “predistribution” by the market, albeit one driven by lack of government action to work counter to the forces driving greater inequality. That said, inequality has been compounded by a tendency towards reduced progressivity of the tax and transfer system, including a fall in top income tax rates and reduced taxation of investment income. Inequality has also been compounded by cuts to income support programs for the working age population, notably Unemployment Insurance and social assistance which became much less “generous” in Canada in the 1990s. (See Banting and Myles, 2013.) In Canada the tax and transfer system still redistributes significantly from the more to the less affluent, but its impact was reduced from the early 1990s even as inequality in market income increased. In fact, Canada has shifted from being one of the most redistributive countries in the OECD to one of the least redistributive.

To summarize my argument to this point, rising inequality is the result of the deliberate reversal of the post-war social contract, combined with the more anonymous economic forces of globalization and technological change. This has set the stage for pernicious social consequences and poses the clear danger of a prolonged period of economic stagnation.

Reversing the trend towards extreme inequality will require, at the most abstract level, a re-embedding of capitalism within society, and a re-balancing of capitalism and democracy. The need for this was best argued by Karl Polanyi who argued in his seminal work The Great Transformation that labour, money and nature are “fictitious commodities” and that the utopian drive to a pure capitalist free-market economy inevitably brought into play a counter movement. Labour was commodified, but then decommodified to a degree by unions and the welfare state which gave labour some bargaining power. Money was subjected to some degree of social control through central banking and government regulation of finance. T.H. Marshall drew attention to the steady shift from liberal rights such as the right to property and civil liberties, to political rights as as democracy came into being, to the rise of social and economic rights to welfare independent of the market. Social democrats championed this rebalancing of government and the market, and of democracy and capitalism, but it was accepted in the post-War era by capital and by much of the right due above all to the searing experiences of the Great Depression and the War against Fascism.

We cannot, however, easily restore the post-War welfare state that presupposed a strong labour movement rooted in the industrial working-class, a solidaristic ethos, the existence of a socialist alternative, and a system of nationally rooted capitalisms in which governments could effectively regulate national economies. Today’s context is one of much greater individualism, a weakened labour movement, and a hyper mobile, globalized capitalism in which corporations create and recreate cross border value chains and can usually bend governments to their will It also has to be borne in mind that, to a degree, the post-War welfare state contained its own contradictions. A strong labour movement combined with full employment set the stage for a growth and profitability crisis for which social democrats had limited solutions, setting the stage for those who followed in the steps of Hayek and Friedman rather than those of Keynes.

Rising inequality has brought forward widespread calls for a shift to more redistributive policies, perhaps most notably the call for a guaranteed basic income financed from progressive taxes or, in the case, of Pikkety, a global tax on wealth. While changes to the tax and transfer system can always be made to redistribute income and wealth, the political viability of such an agenda is problematic. Political scientists have drawn attention to the paradox of redistribution. As a matter of historical experience, the most redistributive policies have been enacted in those countries in which market incomes have been most equally distributed. In the heyday of Swedish social democracy, wages were remarkably equal due to strong unions and a solidarity wage policy, and the state then also redistributed through the world’s most advanced welfare state. Meanwhile in the United States, a weak welfare state has been greatly eroded rather than strengthened even as as inequality has mounted.

Rising inequality is politically self reinforcing to the degree that it increases the distance between the rich and everyone else, what has been termed the “secession of the affluent” to gated communities and private elite universities and high quality privatized health care. Is it really politically viable that the rich will consent to ever increasing taxation to fund a decent standard of living for the rest of us if already extreme market inequality continues to increase?

If the answer to that question is negative, then something must be done to equalize market incomes. It is at this point that many mainstream economists and policy makers underline the importance of education and skills training, and that is entirely reasonable to a degree. But unless there is a rising proportion of good highly skilled jobs, more education will simply expand labour supply and increase competition for the few good jobs that remain, further pushing down wages.

Many on the left will rightly argue that a key need is to recreate a strong labour movement, perhaps based upon effective global promotion of core labour rights and labour and social standards, not to mention basic democratic rights. A global labour market and skills agenda to reconnect worker living standards to economic growth has been championed by the ILO and has merit.

But even if progress was made on a redistributive and progressive labour market agenda, recall the argument above that the stagflation crisis of the 1970s opened the way for the return of the right. In that context, some social democrats argued that we had to move beyond full employment, regulated capitalism to a left alternative combining a market economy with much greater levels of social ownership of the means of production in place of predominantly private ownership. Rather than the Communist agenda of state ownership, market socialists have generally favoured promotion of widely dispersed social ownership, including not just crown corporations but also cooperatives and public owned investment funds, including public pension funds. Rudolph Meidner, the chief economist of the trade union movement in Sweden, with the temporary support of the Swedish government, championed the recycling of surplus profits to pension supplementary funds that would gradually replace large concentrations of private wealth. Meidner assumed that workers would discipline their wage demands to maintain full employment if capital becomes purely functional, a source of real investment to boost living standards, rather than a source of wealth for a privileged class. Other market socialists have argued for an expansion of government controlled financial institutions to steer the economy and earn returns for the state.

This thought can be combined with the key insight of Mariana Mazzucato that major technological leaps require more than private sector entrepreneurship. Specifically, she argues that if we are to deal with major new challenges such as the needed decarbonization of energy production, the state must lead the way through planning and support for major new investments. Even venture capital funds fear to take big bets on largely unknown technologies. If the state does not lead the way, Mazzucato further argues that public investments should be made for the long term, such that the returns flow to citizens and not just the owners of corporate assets.

How then can we return to an era of shared prosperity? Part of the answer is to expand social ownership of capital, as well as rebalance the bargaining power of labour and capital. This is not a call for state socialism, bur rather for a significant expansion of socialized capital in highly diversified form, including through the assets of public pension plans (such as would be boosted if we expanded the Canada Pension Plan), though government support for cooperatives and community run investment funds, through the expansion of public investment banks like BDC and EDC, and through new crown corporations at different levels of government. These funds would continue to operate in the market and in a context of mixed public and private ownership, but might expand over time.

Such an agenda, to make capital ultimately a function rather than a social relationship, may seem utopian. But it is less utopian than trying to achieve greater equality without socializing wealth. And the alternative of business as usual will certainly be no utopia if the inexorable rise of economic inequality continues.

References

Banting, Keith and John Myles (Editors.) Inequality and the Fading of Redistributive Politics. UBC Press. Vancouver and Toronto. 2013.

Corak, Miles. “Income Inequality, Equality of Opportunity and Intergenerational Mobility.” Institute for the Study of Labour, Discussion Paper N. 7520. July, 2013.

Hacker, Jacob S and Paul Person. Winner Take All Politics. Simon and Schuster. New York. 2010.

Krugman, Paul. The Return of Depression Economics and the Crisis of 2008. W.W. Norton and Co. New York and London. 2000.

Mazzucato, Mariana. The Entrepreneurial Stare: Debunking Public vs Private Sector Myths. Anthem Press. London. 2014.

Piketty, Thomas. Capital in the Twenty-First Century. The Belknap Press. Cambridge and London. 2014.

Stiglitz, Joseph. The Price of Inequality. W.W. Norton and Co. 2012.

Wilkinson, Richard and Kate Pickett. The Spirit Level: Why Greater Equality Makes

Societies Stronger. Bloomsbury Press. New York. 2009