The following are remarks delivered by Jonathan Sas upon receipt of the 2024 Rik Davidson Book Prize for his co-authorship of ‘Seeking Social Democracy: Several Decades in the Fight for Equality,’ by the journal Studies in Political Economy at Carleton University on November 15, 2024.

Speaking on “Ed Broadbent, the Internationalist” Sas reflects on the international scope of Ed Broadbent’s life and work, and his lasting belief in “social democracy without borders”.

It is an honour to receive this award. Ed would have been very gratified with the recognition that his book is a serious contribution, beyond mere biography or political history, to the realms of political ideas and political economy.

And he’d have relished getting to spend an entire afternoon in an academic setting discussing ideas and engaging, as he always did, earnestly in dialogue and also critique.

I’ve been in an ongoing conversation with Ed about politics and literature for more than a decade. That conversation has changed since his passing.

But in a real sense, it continues. And it continues because I go through an exercise almost daily wondering what Ed would think about this or that article, or the latest undignified, rights-shredding move of a provincial Premier, or the latest intrigue in the infighting of the Federal Liberals, to which he’d have delighted in (though, not too much).

For months I’ve felt this urge to call him and talk his ear off about Phillippe Sands’ masterful book East West Street, chronicling how the mass violence of the Shoah shaped the lives and deaths of several individuals and families, including two Jewish lawyers and survivors, who would go on to play instrumental roles in the genesis of genocide and crimes against humanity becoming norms of international law.

I didn’t fully appreciate what a gift our friendship was, in the way you never really can appreciate before someone dies.

One thing I truly admired about Ed, to use a turn of phrase he used, is that he didn’t “genuflect to ideology.” He was always interested in understanding the facts, the material, and ideational factors at play in any situation. He was open to learning more, adjusting, sharpening, as he talks at length about doing in our book when it came to feminism and Indigenous rights.

Nevertheless, Ed was moored in a core of social democratic principles; in a political project based on decommodification and the expansion of social and economic rights. That clarity of Ed’s, a way finder in the dark, is like a tonic to me. I’ve been missing him rather acutely these past weeks. More than in the wake of his passing.

Part of it is the far-right winning state power in the US, and in so many other places, its rumbles now reaching a steady drum beat here in Canada. If you read Ed’s writing in the last years of his life, in this book and beyond, you’d know he understood how fertile the ground was for the far right to ascend. He was clear eyed about the material conditions enabling its ascent:

As global inequality remains largely untouched by Western governments, its social consequences are becoming more violent. In our market-dominated society, severe inequality has increasingly come to be accepted as ineluctable and even necessary — and the resulting discontent is compounded by a sense that decision-makers are unable or unwilling to do anything about it.

Whether we look at Canada or abroad, the various sources of insecurity are similar: the rising cost of living for ordinary people and extreme concentration of wealth at the top; the breakneck pace of technological change and damage to the global environment on an industrial scale; racist attacks on the principles of multicultural pluralism and the related demonization of immigration as the source of societal ills. — Seeking Social Democracy, p. 227

Doesn’t that last line hit hard in light of the anti-immigration discourse right now? But even more present in my conversation with Ed these past months has been the destruction of Gaza. Or more specifically, the near complete Israeli impunity and varying degrees of Western complicity and impotence to acknowledge let alone stop the live-streamed atrocities.

Ethnic cleansing, deliberate targeting of civilians, starvation, killing journalists — the list is too long to enumerate here. A key consequence, beyond the scale of human misery, is the evisceration of any legitimacy in the key post-war institutions, norms, and covenants that insist on the universality of human rights.

These of course, are covenants and institutions Ed was deeply committed to and fought for Canada to be deeply committed and accountable to. They were at the core of how Ed practiced his commitment to internationalism.

Until we wrote the book, I must admit, I didn’t quite understand Ed’s deep commitment to the UN Covenant on Civil and Political Rights and the UN Covenant on Cultural, Economic and Social Rights. Part of this, I think, is the era I grew up in. I associated the multilateralist human rights discourse with liberals like Michael Ignatieff. And like many, I had turned away from them for any source of inspiration in the wake of the Iraq War and its liberal apologists.

For Ed, these covenants and norms represented the practical application of social democratic principles. Emerging from the ashes of the early twentieth century economic crises and world wars, and contending with the liberation struggles of post-colonial movements to help contest or at least constrain global inequities and western imperialism, “rights” were a means to making social democratic aims real and enforceable.

Ed recounts in the book, in a wonderful flourish, how he was influenced by meeting students from different backgrounds:

University life expanded my political horizons. As an undergraduate, one of the co-ops I lived in included students from the Caribbean and India who vividly discussed the brutality of British imperialism as well as Hungarian refugees from the Soviet oppression after 1956. Later, while at the London School of Economics, I attended an unforgettable lecture by Historian Eric Williams, who was soon to become the first prime minister of Trinidad and Tobago. Speaking to a packed hall, in an extraordinarily powerful address, he used a metaphor to describe Britain’s attitude toward the colonies that has stayed with me to this day: “They take an orange, and they squeeze and squeeze and squeeze. When there’s no life left in it, they throw it away.” — Seeking Social Democracy, p. 70

For Ed, social and economic rights were the bedrock of “freedom.” That was true in the domestic arena, but this belief animated Ed’s very significant contributions to international diplomacy and engagement in practice.

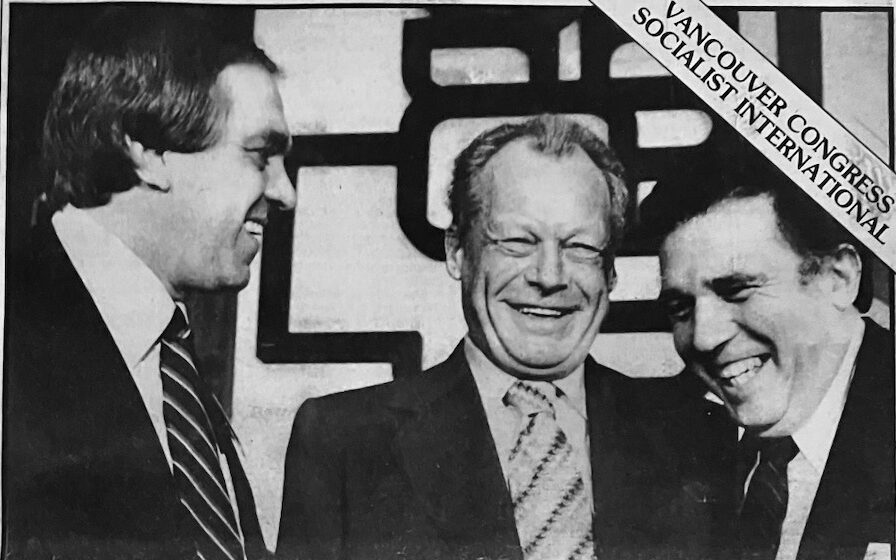

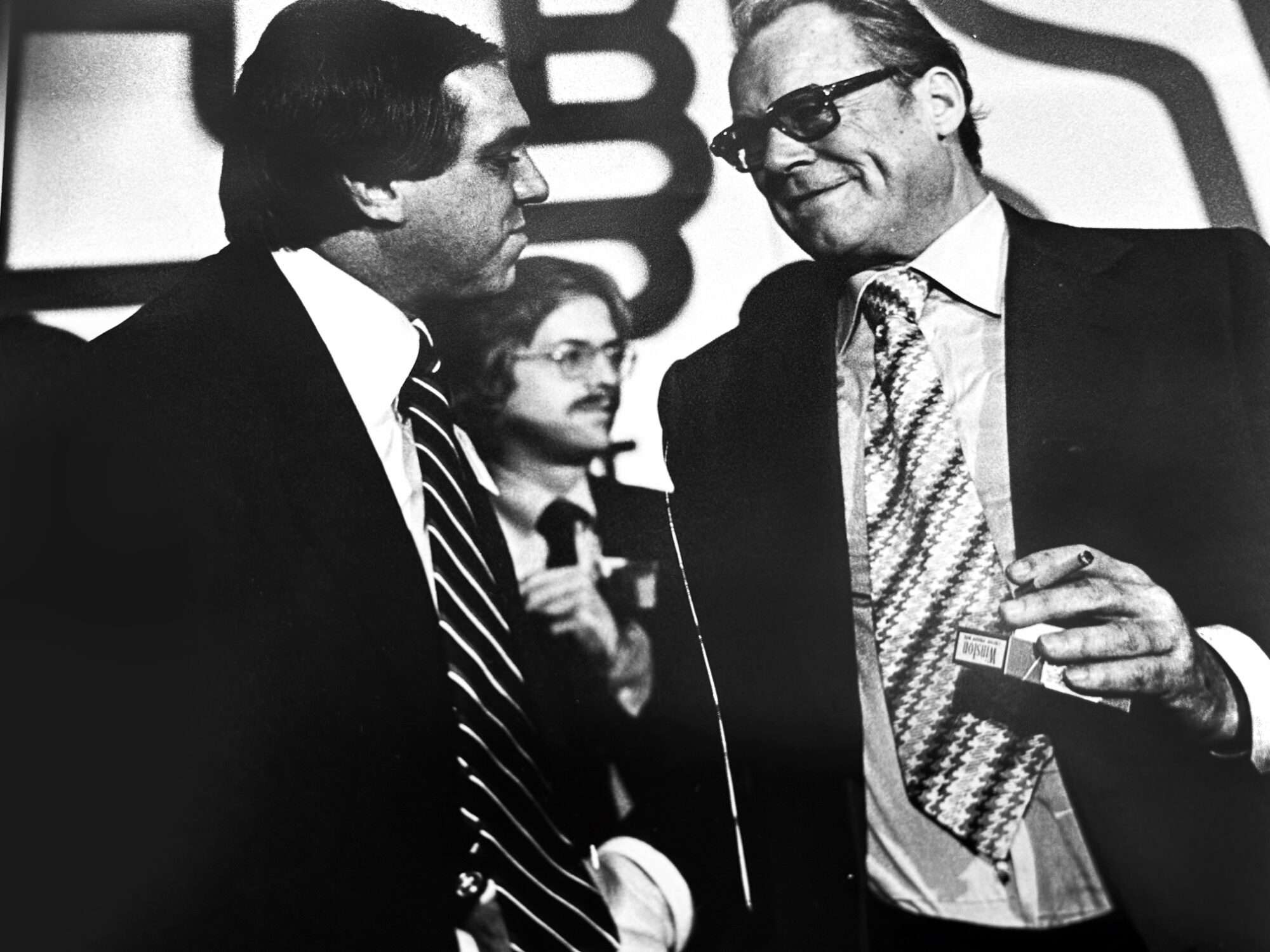

In Chapter Six of the book, entitled “Social Democracy Without Borders,” readers get a window into his nearly two decades of activity in the once proud Socialist International. There, Ed became a close friend and trusted colleague of former German Chancellor Willy Brandt. Brandt, among other world leaders, shaped Ed’s politics and reinforced his conviction that the goal of any social democratic party ought to be to form government, and not settle for being the “Conscience of Parliament.”

One of the reasons Ed was such a great politician was that he didn’t condescend to ordinary people. Indeed, he thought he could learn from all sorts of people — that they knew things he didn’t. In his words, people were due your respect, and different political orientations were to be engaged seriously. That democratic spirit and commitment to pluralism, I think, is one of the reasons you saw such an outpouring of admiration for Ed at his passing.

I think there is an analogue here to how he approached his international engagements. He was eager to learn, to stretch, to take seriously the practice of social democracy in the international arena. The federal [New Democratic Party] today, I submit, would benefit greatly from the same curiosity.

At the Socialist International, Ed was engaged in important diplomatic efforts in Central America, taking on missions on behalf of Brandt to broker peace, and advocate for social movements against an imposing current of repressive US foreign policy that propped up violent regimes in El Salvador and Nicaragua. As he recounts in detail in the book, he even became an interlocutor with Cuba’s Fidel Castro.

This was all undertaken while party leader of the NDP. Ed’s speech to the 1978 Socialist International Congress held in Vancouver, and an image of which is displayed here, is reprinted in full in the appendices of the book. In it, he makes an impassioned case for countering the outstretched power of the modern multinational corporation.

Just as we want to redistribute wealth within Canada,” he said then, “we also want to do the same on a world basis. We want to respond to the moral obligation to combat the famine, the malnutrition, the poverty and hopelessness which makes wretched the conditions of so many millions.”

Ed would go on to carry his deep concern with the inequality produced by unfettered markets and the antidote of social and economic rights into his life after Parliament. In Chapter nine, entitled “Globalization and the Struggle for Equality,” Ed explores his time at the helm of the International Centre for Human Rights and Democratic Development (Rights & Democracy). His appointment was made by then Prime Minister Brian Mulroney at a moment where a very different Tory tradition was still alive in Canada.

Ed accepted the role in part because of the explicit mandate it had to implement the International Bill of Human Rights throughout the developing world, including the covenants on social and economic rights. At Rights & Democracy, his commitments to these covenants would butt up against the tidal forces of global free trade and corporate power.

Whether advocating for trade unionists in China, garment workers in South Asia, or for Indigenous rights here in Canada (including intervening to try and end the so-called Oka Crisis), Rights & Democracy rejected the narrow neoliberal framework of democracy promotion of the time. It is bitter, if not a bit rewarding, seeing all of the issues Ed raised about unbridled free trade emerge as a new consensus. To say nothing of the renewed interest in industrial strategies, I digress.

For Neoliberals, the very idea of collective altruism or community obligation outside participation in the marketplace was and is anathema. Much as totalitarianism had sought to eradicate the personal in favour of the collective, so neoliberalism has sought to eliminate the political pursuit of the public good in its triumphant promotion of the private self. Through my work at Rights & Democracy, I was able to see quite directly what this new and market-driven conception of human society ultimately meant. — Seeking Social Democracy, p. 188

An early trip of Ed’s at Rights & Democracy was to the occupied territories and to Israel. “There is still time to avoid de facto annexation of the occupied territories,” Ed pleaded in a piece for The Globe and Mail in February 1992, also referring to the Geneva Conventions and UN Declaration on Human Rights in his article.

A curious, if telling dimension of this trip: one of the groups Ed met with, and as he explained to us co-authors for the book, Rights & Democracy only visited countries upon invitation from civil society and human rights NGOS — was the Israeli human rights organization B’tselem. Rights & Democracy was an early funder.

It was this ongoing support for B’tselem, and clear position on rights violations by Israel, that led Stephen Harper to shutter Rights & Democracy in a nasty saga Ed discusses in the book.

So what am I trying to argue here? My conversation continues, but what Ed’s legacy keeps saying to me from beyond the void is not to abandon the universality of human rights, and a socialist fight for social and economic rights. The West and the so-called liberal internationalists have abandoned the project, or even the appearance of it.

But maybe we shouldn’t.

I want to leave you with one longer passage from the book that exemplifies Ed’s internationalism. It was published in The Globe and Mail in 1986, just as Ed was becoming the most popular leader in the country; a time when many leaders of social democratic parties in the global north were retreating from their convictions.

But not Ed.

The world of a politician is a world of light and shadow. Never merely pragmatic, it is always moral. For us in the international social democratic movement there has always been the difficulty of reconciling certain universal principles with their application in a variety of countries with widely divergent histories.

It is a problem, it is difficult — but it must be done. We apply the principles of equality, liberty and economic justice constantly within our own nations, of course; this is a difficulty we take for granted. But just as we must make critical judgments at home, so, too, must we when we look at other countries. Cultural and historical differences must certainly be taken into account, but they never absolve us of the obligation to judge, decide and act.

When we talk about democracy, pluralism, religious freedom, tolerance, human rights and self-determination, we are not giving voice to mere abstractions relevant only to a few nations; we are talking about human values and ideals that we believe desirable for all people, at all times, in all parts of our world. — Seeking Social Democracy, p. 274

Thank you.