The race is on. Monday’s U.N. climate summit, entitled “catalyzing action”, was designed by Secretary-General Ban Ki-moon as a sort of opening stage of the Tour de France, which like that epic race, ends in Paris.

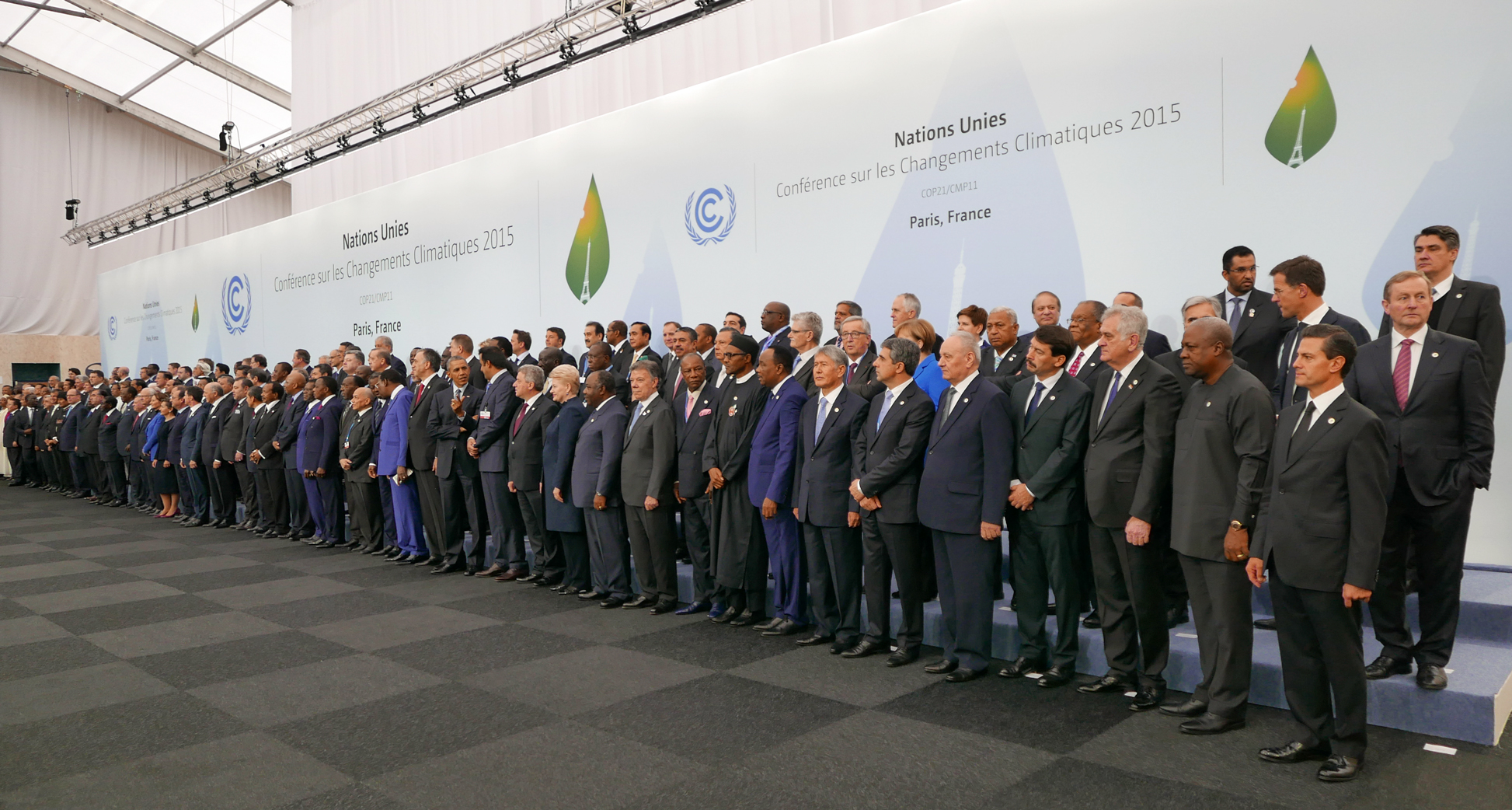

In this case, the aim is to have a new international treaty on climate change ready for signing at the 21st Conference of the Parties to the U.N. Framework Convention on Climate Change in Paris in December 2015. It too will have various stages, with a more-or-less non-stop cycle of shuffling back and forth between national capitals and negotiating sites for increasingly weary negotiators. It too will have the odd background threat of doping scandals: efforts to discredit the science and scientists behind Inter-governmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) statements, or the breakdown of trust between key countries.

The Summit itself was never intended to produce a breakthrough in itself. Rather, it was a sort of jamboree of announcements designed to build a sense of irresistible momentum towards a deal in Paris. Ban was certainly able to bring out an impressive list of such announcements, synthesizing them to present the results as a sort of consensus for more action. The myriad announcements by governments and others function as a ‘tit for tat’ strategy where each promises to act thereby increases the pressure on others to do likewise.

Beyond this general way to understand the summit’s role in global climate politics, four things are worth noting.

First, what is increasingly notable in these orchestrations of statements, actions and mutual cajoling is that the U.N. itself now sees national governments as only one actor among a range of others that need to be involved. In particular, we now see the involvement of major global cities and of large financial institutions. Bringing these actors into the conversation has a couple of effects. On the one hand, it is clear that those actors are in a number ways considerably ahead of most governments in their efforts to pursue a transition to a low-carbon economy. On the other hand, they require action by national governments in order to achieve their own potential.

For example, investors need stable expectations as to a price on carbon in order to be able to shift investment more rapidly towards zero-carbon energy sources, and thus much of the involvement of the investors yesterday was designed to put pressure on governments to introduce such carbon pricing more widely. This dynamic is highly interesting and reflects the continually growing importance of what scholars have called transnational climate change governance – attempts to govern climate change across borders bypassing the U.N. system – and the importance of coordinating between the U.N. system and these novel arrangements.

Second, and connected, was the extraordinary ‘people’s climate march’ on Sunday. The organizers catalogued 2808 marches in 160 countries, and at the main march in New York estimates of the numbers have converged at around 400,000.

While organized mostly by a range of environmental, environmental justice, and faith organizations as an autonomous action to build pressure on the Summit participants, it was nevertheless instrumentalized by the U.N. to become part of the process itself. Ban donned a colourful T-shirt (nicely satirised by John Stewart) and walked with the marchers, in what looks part co-optation of the protestors’ messages, part naïve “we’re all in this together” messaging, and part deliberate effort to situate the U.N. on the side of those pushing governments and others for more aggressive action to reduce greenhouse gas emissions.

But the effect has been to legitimize those organizations, like 350.org, climate justice action, or the transition network that were involved in organizing the march and who are pushing for much more radical and rapid action than the national governments, city managers, and private investors represented in the Summit itself. Activists in those movements should feel like the door is open to press harder for more ambition.

This is important because, third, it is clearly the case, as Rob Stavins and others soberly reminded us prior to the summit, that the mismatch between all the announcements by governments and others, and what is required to meet a more or less universally accepted target of limiting climate change to 2°C above pre-industrial levels, is striking. One can debate the details, but the general thrust of those involved in the march to push for more aggressive action is incontrovertible unless one engages in the idiocies of climate denial. This background condition needs continuously to be borne in mind.

Fourth, while there is not really any country, city, company, or other actor that is really on the path to decarbonization, some are further off than others. For those of us in Canada, the summit was a reminder again (if you hadn’t yet noticed) how far away we are, at least at the federal level, from the rest of the world on this issue.

While other major world leaders didn’t attend (from China and India, for example), Harper managed a deliberate stub by being in New York but not attending. While many countries have now accepted at least the rhetoric and logic of the ‘low carbon transition’ even if their actions don’t yet match their rhetoric fully, the Canadian government is still wedded to a vision of more or less unrestricted fossil fuel expansion.

Again, as in the point above about other actors and institutions, the action in Canada is very definitely at provincial level and in some cities, and it’s also clear from the recent Council of the Federation that Premiers would like to do more. But it’s hard for them to achieve that potential when the federal government is being actively obstructive.

The Canadian problem is in some ways a microcosm of the international dynamic. We have radically uneven emissions levels and trajectories across the country. We have multiple levels of government, all of which have to act but which have incentives to free-ride on the actions of others and that provide multiple sites for those opposing action to bring pressure to bear. But we also have much momentum for action and experience of policy successes (the Feed in Tariff in Ontario, the carbon tax in BC, emissions trading in Quebec – although it’s a little soon to judge, city-level action in Toronto in particular).

The task for those wishing to move the issue forward, in Canada or internationally, is on the one hand to keep up the pressure from movements such as the people’s climate march, which makes it politically impossible to backtrack, and on the other hand to get much more creative in identifying how the actions of cities, provinces, businesses, investors and activists can be enhanced by strategically astute action by national governments and their negotiators at the U.N. process.

Then we may be able to race down the Champs-Elysées with some sense that all may be wearing the maillot jaune.