In a medical sense, COVID-19, as highly contagious as it is, can be thought of as the great leveller. No one has immunity, and we face the health risk of this virus with a sense of our common humanity.

But in a socio-economic sense, it is not as contagious. The jobs some of us hold give us an economic immunity, and we face the economic risk of this virus with a very different sense of our interconnectedness.

Last week Statistics Canada reported that more than one million jobs were lost as social distancing and mandated work shutdowns took force. A further two million people saw their hours of work fall dramatically, implying that over three million Canadians were directly impacted.

The big hope, the hope upon which the entire government response rests, is that the COVID-19 economic shock will be temporary. The goal is to freeze the economy until the winds of illness pass by, allowing us to start again where we left off. Public policy is focused on the challenge of adjustment and rebound.

But Statistics Canada’s look into the socially distanced economy also reveals longstanding inequalities that have been growing wider and wider for decades.

For many families, the bottom end of wage inequality means an insecure standard of living and lower prosperity for the next generation.

The usual economic parable claims that this is the price paid to foster growth and prosperity, and eventually more prosperity for everyone. We need to adjust to win.

The market has sent a signal: tool up, get better skilled, move elsewhere and move onward. The next and better job is just around the corner!

And after all, if you have a job, even if you need more than one to stay afloat, there is always a sense of hope, a shred of dignity, the aspiration of a better tomorrow. Income inequality is easier to ignore in a full employment economy.

But the great revealer has arrived in the form of a virus, its economic fallout showing almost perfectly the divides between those who are vulnerable and those who are not.

Now, some of us do work that is not public facing.

Some of us do work that is flexible and supported by technology and computers.

And of course some of us do work that gets us an income well above average, offering security, health, a home with space, and a comfortable family life.

This work gives us an economic immunity.

What is the big deal about working at home if you normally spend half your time working from an airplane seat?

But underlying Statistics Canada’s report are some dramatic differences.

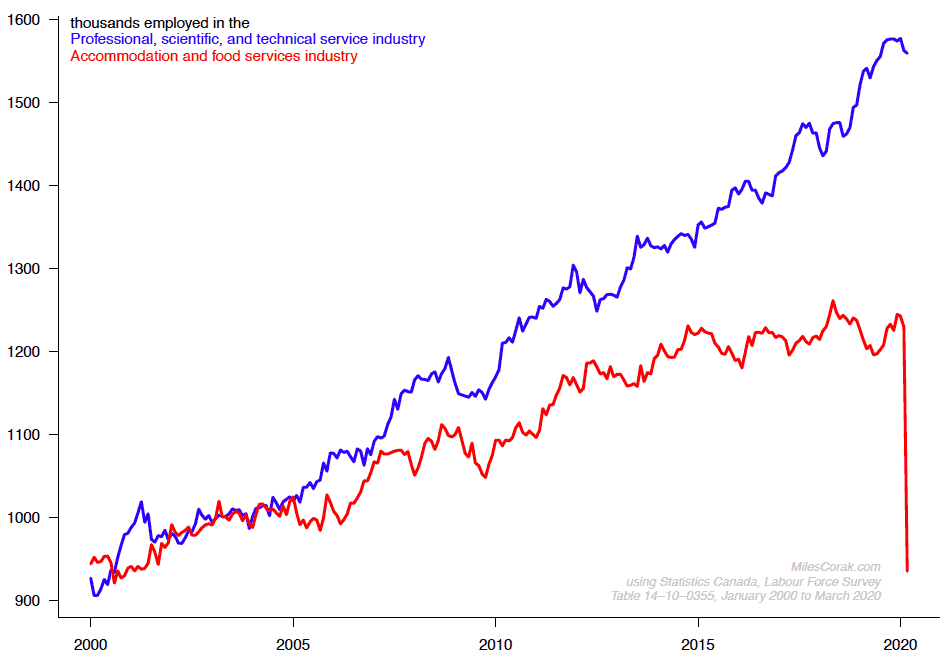

The employment change among managers and those working in professional, scientific, or technical jobs was “decimal point dust,” but 300,000 people working in accommodation and food services lost work, a fall that wiped out 20 years of growth.

The foot soldiers in this very first economic battle against COVID-19 were the young and women, those who work in part-time and temporary jobs, with no union contracts and lower wages. Students and those who were already unemployed were also out of luck finding their next job.

Now that we are collectively facing a health risk that is spreading across space, we’ve been given the opportunity for empathy with many people who individually confront risks that repeat over and over again during the course of their lives, an accumulation of bad draws over time that leads to lower and more precarious incomes, housing that is less stable and of lower quality, families that are less secure.

In much of this there is no question of merit and just desert, it’s just bad luck.

It is nice for Premiers and Prime Ministers to thank truck drivers and grocery store clerks for their essential work, but it will be hypocrisy of the highest order for our governments to only hope to start up again where we left off.

Inequality has been robbing many Canadians of security, prosperity, and dignity for decades. That is what COVID-19 reveals.

No, we don’t just have an adjustment problem; we have—as we have long had—an inequality problem.