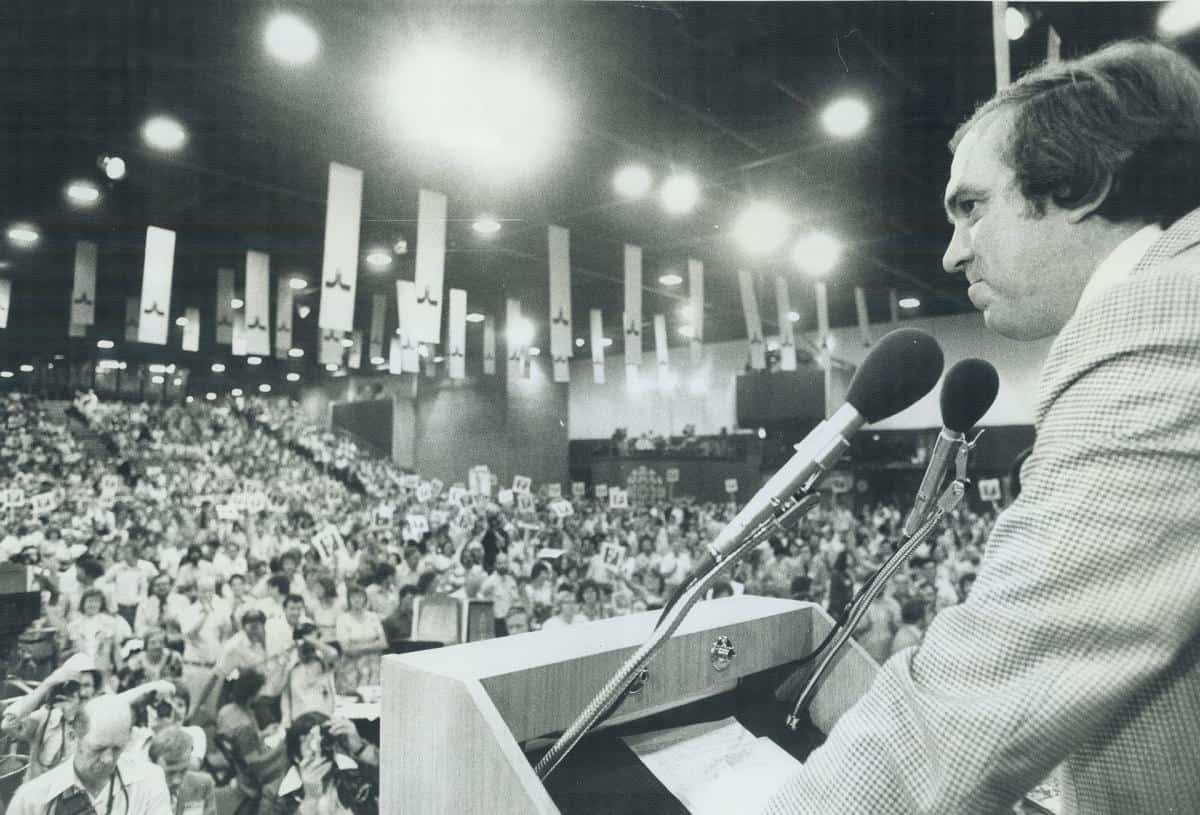

Remarks reflecting on the legacy of Ed Broadbent delivered by Professor Frances Abele at the 2024 Progress Summit on Thursday, April 11, 2024 in Ottawa.

It is my honour to speak this morning about Ed Broadbent’s ideas about social democracy and his hopes for the future. Towards the end of his life, Ed was thinking about the future a good deal. His dominant emotion was optimism. That is perhaps surprising, but it is true. He was particularly inspired by the idealism and energy of the generations that have recently come of age — the so-called millennials and the generation born after them.

We are in a moment when not only Pierre Poilievre but also numerous respected pundits are repeating the nonsense that Canada is broken. Canada is not broken. We have problems. Some are self-inflicted, like the severe shortage of adequate housing; others are only partly our fault, like the climate crisis that is upon us. More than most countries on this planet, we have the means to work on all of them. What we could use more of is a positive, detailed, concrete, ambitious vision of the kind of new society we now want to build, suitable to our present circumstances. We need one that deals effectively with injustice and dysfunction while also looking forward, providing inspiration and hope.

This is why Ed agreed to work on his last book, Seeking Social Democracy, with Jonathan Sas, Luke Savage and me. Of course he thought a good deal about what he had learned in his long career, but he meant to offer an intervention in our present moment, speaking to the younger people who are the future.

In a nutshell, this was his message. “Activists today,” he wrote, “can overcome the impact of the rightwing forces of our time. We can build an alternative democratic agenda, creating more equality and decommodifying more of our lives. We don’t need perfection as a goal. We require simply compassion and thoughtful engagement. There is no guarantee that social democracy will triumph. But it is by far our best alternative, very much worth our political energy.”

So what to do with that energy? Best that you read his book, but let me offer four brief points.

First, Ed’s vision was a profoundly practical one. He did not favour millenarian thinking or radical rhetoric. Along with his comrades and role models, Tommy Douglas, Willy Brandt and Olaf Palme, he believed in leadership and discussion towards the building of public consensus on social democratic goals. In practical politics, he accepted that compromise was usually necessary. Not to find the middle ground, but to make slow and steady progress towards an ideal. He believed that this approach is the one that is most compatible with a healthy democracy, because experience will lead people to support those measures that are actually in their interest.

Second, concerning rights. Ed frequently used the language of rights, and they were a fundamental aspect of his vision of social democracy. He believed that democratic citizenship comes with individual responsibilities, and individual rights. But he did not see either of these as primarily a matter of individual effort or will. He saw that we need a society that is structured so that citizens normally enjoy the conditions under which they can flourish as active members of society. For sure this entails the presence of legally protected political rights — freedom of speech and freedom of association. These are essential, but not sufficient. Free citizens require also the economic and social rights that confer basic security, freedom from want, yes, but also freedom to flourish — to be educated and to otherwise develop their capacities, to find leisure and pleasure in society. These are the goals of democratic socialism, for Canada and for all the citizens of the world.

For Ed was an internationalist. Early in his work as an elected politician, he became a Vice-President of the Socialist International. This was at a time when that body had become a real force for human rights and democracy in many countries, particularly in Central America and the Caribbean. His internationalism was of a piece with his commitment to human rights at home. He was proud of Canadian John Humphrey’s role in drafting the Universal Declaration of Human Rights. After he left politics Ed went on to lead a crack team of pragmatic idealists at the nongovernmental organization, Rights and Democracy. In all these roles, he frequently spoke to Canadians about peace and about events abroad, more so as neoliberalism took its brutal course. All of this work was based upon the same principles he brought to Canadian politics — seeking solutions to injustice and suffering, and respect for the views of those he was working with.

Finally, Ed had a full vision of the need for democratic control of state and corporate power. Partly this entails entrenched rule of law and Charter protected freedoms. Together these enable — though they do not guarantee — social democratic progress. And they are in fact the result of generations of struggle by workers and others. In turn, the state so shaped itself must have a strong capacity to regulate and counterbalance corporate power, which is today a taller order than it has ever been.

Early in his career, in the mid-twentieth century, Ed devoted a great deal of thought to what we call workers’ control, and workers’ participation in the economic institutions upon which they depend for their livelihood. Things have changed a good deal since then, but the need is even greater. However containment of corporate power in a capitalist system might be realized, in Ed’s view, it began with and depended on the presence of strong independent unions and vibrant and creative civil society organizations. He did not see the counterbalancing of corporate power as entirely a negative matter, of blocking. Rather he was interested in harnessing whatever forces for good were available. This is the work of social democracy.

As he said:

In the 21st century… social democracy remains the form with the greatest potential, no more, no less, for liberating the creative, cooperative and compassionate possibilities of humanity and offering dignity to all.

So we can work on that.