The 2024 Ellen Meiksins Wood Lecture was held on Thursday, May 30th in partnership with Toronto Metropolitan University’s Faculty of Arts. A special thanks to TMU Interim Dean of Arts Amy Peng for hosting this Broadbent Institute event.

Ellen Meiksins Wood was one of the left’s foremost theorists on democracy and history, and often promoted the idea that democracy always has to be fought for and secured from below, never benevolently conferred from above. The Institute founded the annual Ellen Meiksins Wood Prize & Lecture to honour Professor Wood’s legacy as an internationally renowned scholar and to bring her work to new generations of Canadians.

The Ellen Meiksins Wood Prize is given annually to an academic, labour activist or writer and recognizes outstanding contributions in political theory, social or economic history, human rights, or sociology.

Each year’s recipient also delivers the Ellen Meiksins Wood Lecture.

The 2024 Ellen Meiksins Wood Lecture was delivered by economist Professor Isabella Weber. She is awarded the 2024 Ellen Meiksins Wood Prize in recognition of outstanding contributions to political economy research that helps to defend the working-class in a time of economic crisis.

Her lecture, entitled Profits, Inflation and Survival in an Age of Emergencies: Why We Need a New Paradigm, demonstrates how prices on essentials have risen, while corporate profits have grown, due to economic shocks induced by pandemics, climate change, and other global events. The lecture helps to equip progressive movements with the information and analysis needed to push back against austerity, and helps to demonstrate why public policies such as public investment, wage gains, and price controls complement a policy toolkit to help ordinary Canadians out of today’s affordability crisis.

Listen, watch or read the full 2024 Ellen Meiksins Wood Lecture.

This lecture has been edited for clarity. Download the accompanying presentation.

2024 Ellen Meiksins Wood Lecture

Thanks so much to the Broadbent Institute for this prize and to Ed Broadbent personally, whom I heard was still involved in the decision making, which is truly moving. Thanks to Toronto Metropolitan University for hosting this tonight and for welcoming me with such warm words.

Just listening to you right now, what really moved me was the sentence this “equipped Canadian progressives with doing something different,” and I would never have imagined that my academic work would be able to do that.

But it’s absolutely thrilling to find that this is the case. And even the day today, having exchanges with a number of progressive Canadian economists from unions and think tanks, has been absolutely thrilling — to see that ideas can actually travel in that way when they are being picked up, and when they happen to break through at the right moment, even under pretty atrocious circumstances to begin with.

When I wrote this article in The Guardian in December 2021, I was pretty depressed with how the inflation debate was going.

There were basically two camps: one camp said that that we should have imposed austerity the day before yesterday camp. This camp basically said, “we need to push down the wages of working people, who are already in the middle of a cost of living crisis, (and who, by the way, are the ones who are carrying the brunt of the burden of inflation) so we should push them down even more. And in the course of doing that, we will push down the whole economy, sacrifice growth, and sacrifice the prospects for investment – especially the investments that we so urgently need for the energy transition that we can no longer wait for.”

On the other side were those economists that were arguing, “well, inflation at the end of the day is just transitory, so don’t worry too much. These are just a bunch of shocks to some sectors. Eventually the shocks will subside and we will come back to the steady waters that we sailed out of.” I also found this an utterly frustrating response to inflation, especially looking at what kind of prices were exploding. The prices that were exploding were the prices of essentials, the prices of things that people cannot do without: the prices of food, the prices of energy, the prices of transportation, the prices of housing and utilities.

I happened to come from a family where we lived on a budget. I remember how my mom would watch the advertisements from supermarkets and try to figure out how she could buy the best food for us so that we could be well fed — that we could be healthily fed despite being on a budget.

If you tell a family like that, “this is intransitory, in two, three years, the storm will be gone,” it’s hypocritical. It’s unbearable. It’s an unbearable message to send especially from someone who is sitting in front of a full fridge, probably in a fancy apartment in New York, or in some pleasant place of the world, making hundreds of thousands of dollars a year and going to the grocery store without even noticing how much they are paying.

So, I felt it was necessary to intervene. I also felt it was necessary to intervene based on the historical research that I had done on inflation since my message was, “There Is An Alternative.” Neoliberalism has told us “There Is No Alternative”; TINA. But at the end of the day, TIAA is what rules. There is an alternative.

If we are trying, it is possible. And I think that this historical research, this attempt at trying to understand the evolution of economics, the evolution of the economy, the evolution of political dynamics in historical time and in its historical complexity, is where my work is linked to that of Ellen Meiksins Wood.

And that’s why I’m absolutely thrilled to be awarded with a prize in her name. Thank you so much.

I also think that my work connects with her in the context of one of her core concepts: market dependence. At the end of the day, what we have been experiencing in terms of inflation, that in many ways centered on the prices of essentials, put the market dependence of people into focus.

The market dependence for the essentials that you cannot do without is through which we experienced inflation. And on that theme, I want to start my formal presentation. I will have to do an extra great job in explaining my charts, which is my ambition anyway.

The title of this lecture is, “Profits, Inflation and Survival in an Age of Emergencies: Why We Need a New Paradigm.” I decided to not make this lecture about settling scores, not make this lecture about who won the inflation debate, but to make this lecture about what we are learning from this inflation debate when we look forward. And, I would argue, that in the worst case scenario, what we have seen in the last couple of years has been a dress rehearsal for what is to come.

Therefore, I want to start this lecture by acknowledging that I think we are living in an “age of emergencies.” These are just some pictures and I probably should have included a picture of Gaza, and I feel a bit embarrassed that I didn’t, but if we look at what is happening in Gaza, and the form of warfare being experienced there is the weaponization of essentials. It’s cutting people off of the absolute necessities of life.

But even in more fortunate places like Toronto, we are living in a world of overlapping emergencies. We can be pretty sure that even in these comfortable places, there will be more supply shocks to come. We do not know when they are going to hit. We also do not know where they are going to hit. But we do know that they are already in the pipeline. If we look at what is happening with climate change, if we look at what is happening with the disintegration of the global political order, and the consequences of this for the stability of production networks and the flow of goods and services around the globe, I think we can be pretty certain that there will be more shocks.

We can be also certain that some shocks matter much more than others. And the shocks that matter are the shocks that hit the essentials, that hit the things that people, or the economy, cannot do without. I would argue that there is no hope for resilience when the firms that control essentials reap record profits from disasters. And that is exactly what we have seen.

All the talk about “resilience” is cheap talk if the incredibly capable, incredibly powerful, incredibly well organized, global, gigantic firms that often have more capacity than whole countries, that organize the essentials, come to profit off of disasters. And I want to give some examples of what I mean by that.

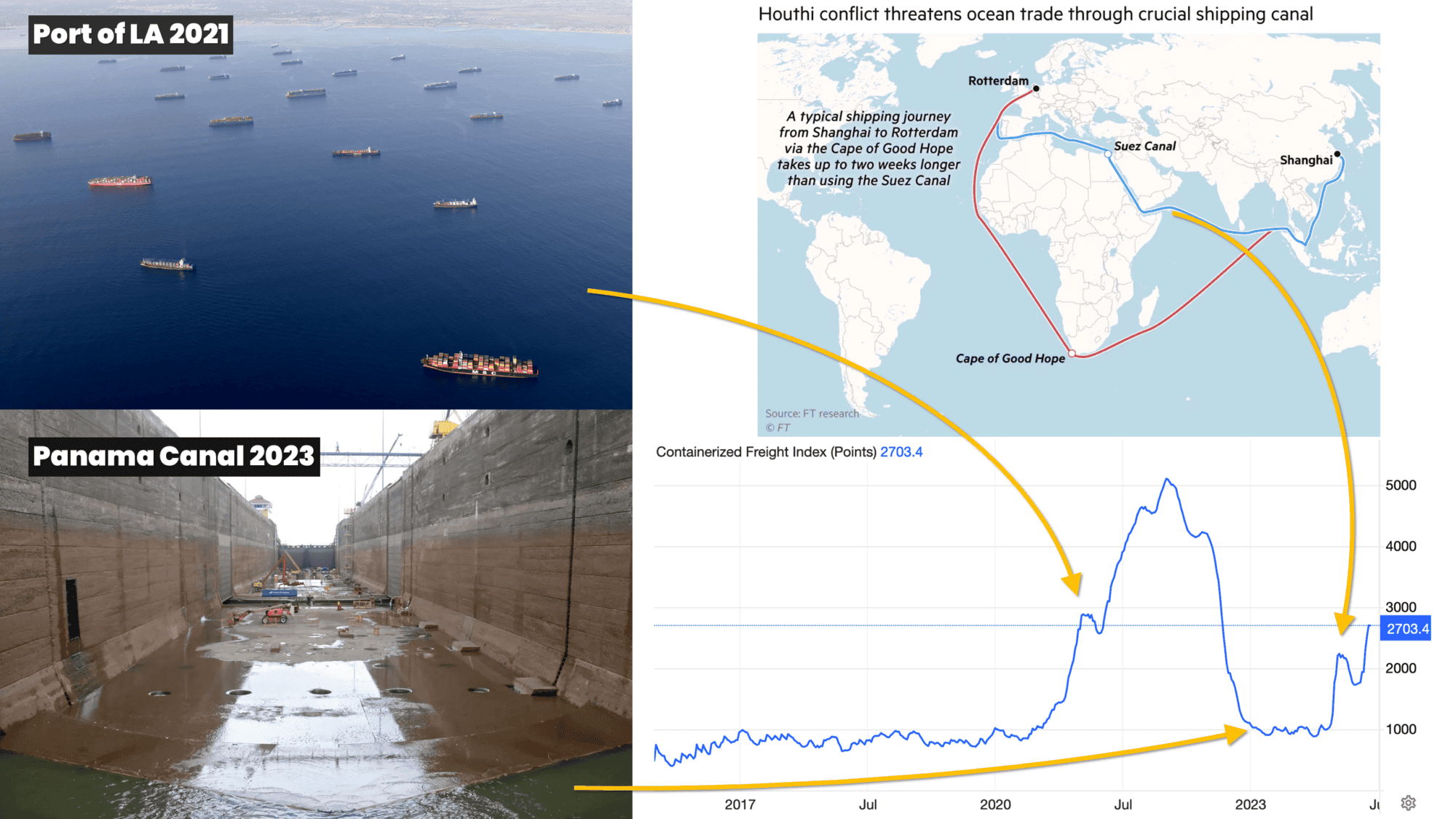

Let’s look at the example of shipping. We probably all remember the news about the traffic jams in front of ports. For example, this is a picture of the Port of Los Angeles, which is one of the most important ports for the United States. The United States is, of course, an incredibly import dependent country for a lot of goods and services. This is a true “chokepoint” in the quite literal sense of the word.

On the bottom left is a picture of the Panama Canal in 2023. A drought had led to water levels that were so low that the traffic flow through the Panama Canal was drastically reduced. On the top right hand side is a map that shows you how much further a ship has to travel if it can no longer pass the Suez Canal, which is, of course, a situation that we are facing right as we speak with the Houthi attacks and the war in the Middle East.

On the bottom right hand side you see a chart of the World Containerized Freight Index. I’ve joked earlier that I am actually following this index, and not expecting anyone else to do so. But I think it’s quite remarkable when you actually look at that index, because you see that it’s been basically flat [until 2020]. The first part of the index is completely boring. It’s basically flat.

And then you see something that looks literally like a tsunami. You don’t even need to see the exact numbers — just look at the line. You see a total tsunami that takes off in 2021, and peaks in 2022, which is the time when we were talking about all the supply chain issues, day-in and day-out. These supply chain issues in many ways were linked to shipping, and then you see at the end of the chart this trend picking up again, which happened exactly in late 2023, when the war in the Middle East started to escalate. You can see this increase again in recent weeks as the situation — the safety of passage — further deteriorated.

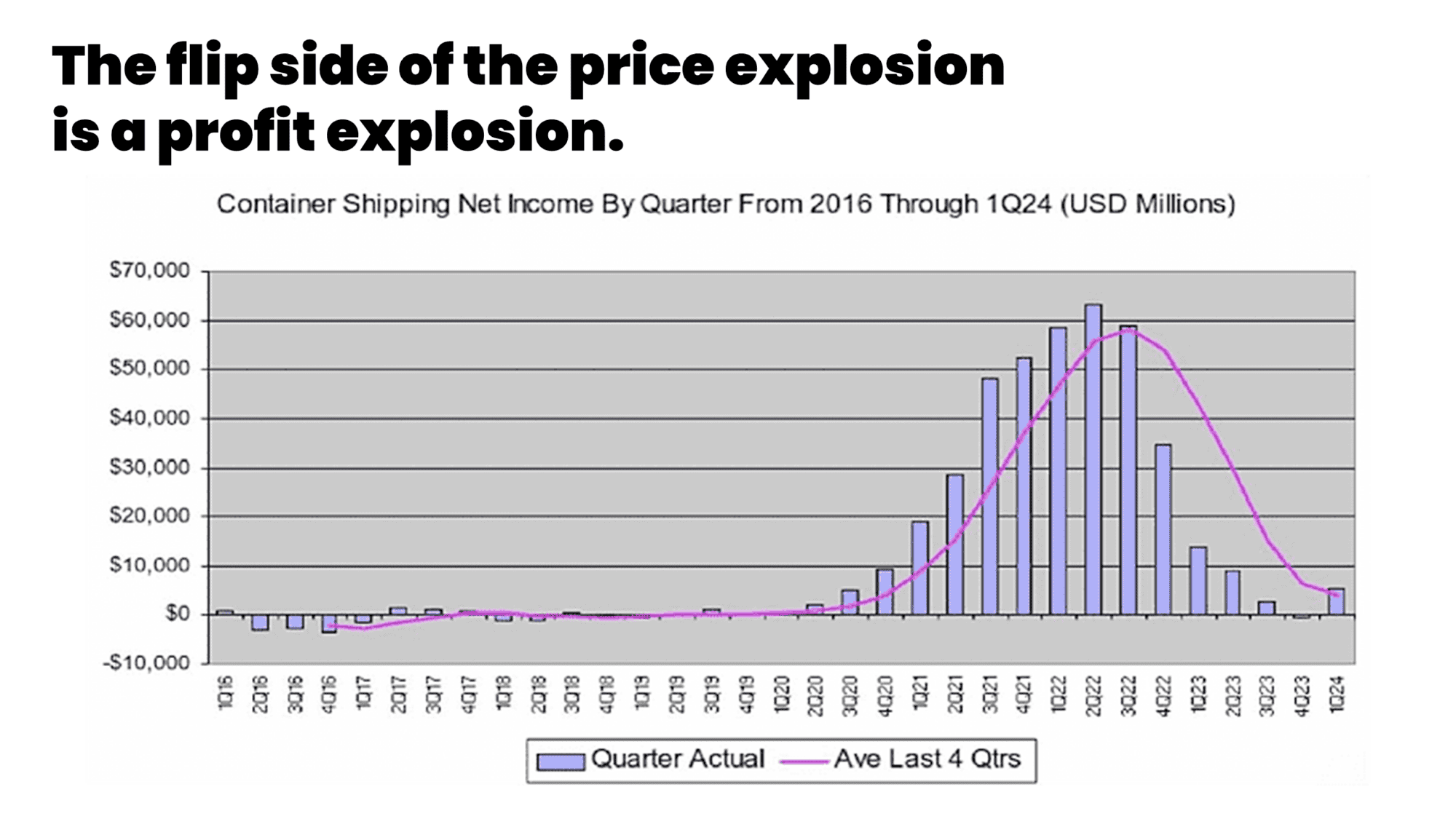

This is one part of the story. If we then look at what the flip side of this explosion of freight rates, then we see there is an explosion of profits, which is pretty unsurprising because the cost structure might have changed a little bit, it might have become a little bit more expensive because they have to hold and wait on their cargo, or they have some supply chain slack, or whatever.

But costs did not explode. They might have picked up where prices exploded, but the result of that price explosion is a profit explosion where profits are the difference between prices and costs, which you see on the bottom chart.

As a recent working paper of the International Monetary Fund points out, we find that spikes in the Baltic Exchange Dry Index, which is one of these freight indices, are followed by sizable and statistically significant increases in import prices, the Producer Price Index (PPI), headline and core inflation, as well as inflation expectations.

You don’t have to trust some unreal, weird economists to learn that shipping costs affect inflation — you can literally read this in IMF working papers. According to this paper, the impact of shocks to global shipping costs are similar in magnitude, but more persistent than for shocks to global oil and food prices.

In other words, these enormous price explosions have systemic implications for monetary stability way beyond the prices in this one sector. If we look at who is actually running the shipping sector, then it’s a handful of companies; it’s literally eight carrier groups that have a share of more than 80% of the global fleet. And these companies, unsurprisingly if we look at the profits in the sector, recorded the best financial returns in their histories.

To just give some examples here, Maersk, a company founded in 1904 so we are talking about a pretty long history of more than 100 years here, had the best financial results in its history in 2022, showing a net profit of $29.3 billion USD. The privately held Mediterranean Shipping Company (MSC) achieved an astounding annual net profit of 36.3 billion EUR in 2022. And in 2022, CMA CGM had been France’s most profitable company, overtaking the likes of TotalEnergies and LVMH, with an annual net profit of $24.88 billion USD.

Now, probably most of you don’t have a very clear idea of what around $30 billion USD looks like, but it is about twice the GDP of a country like Madagascar. This is very, very big money.

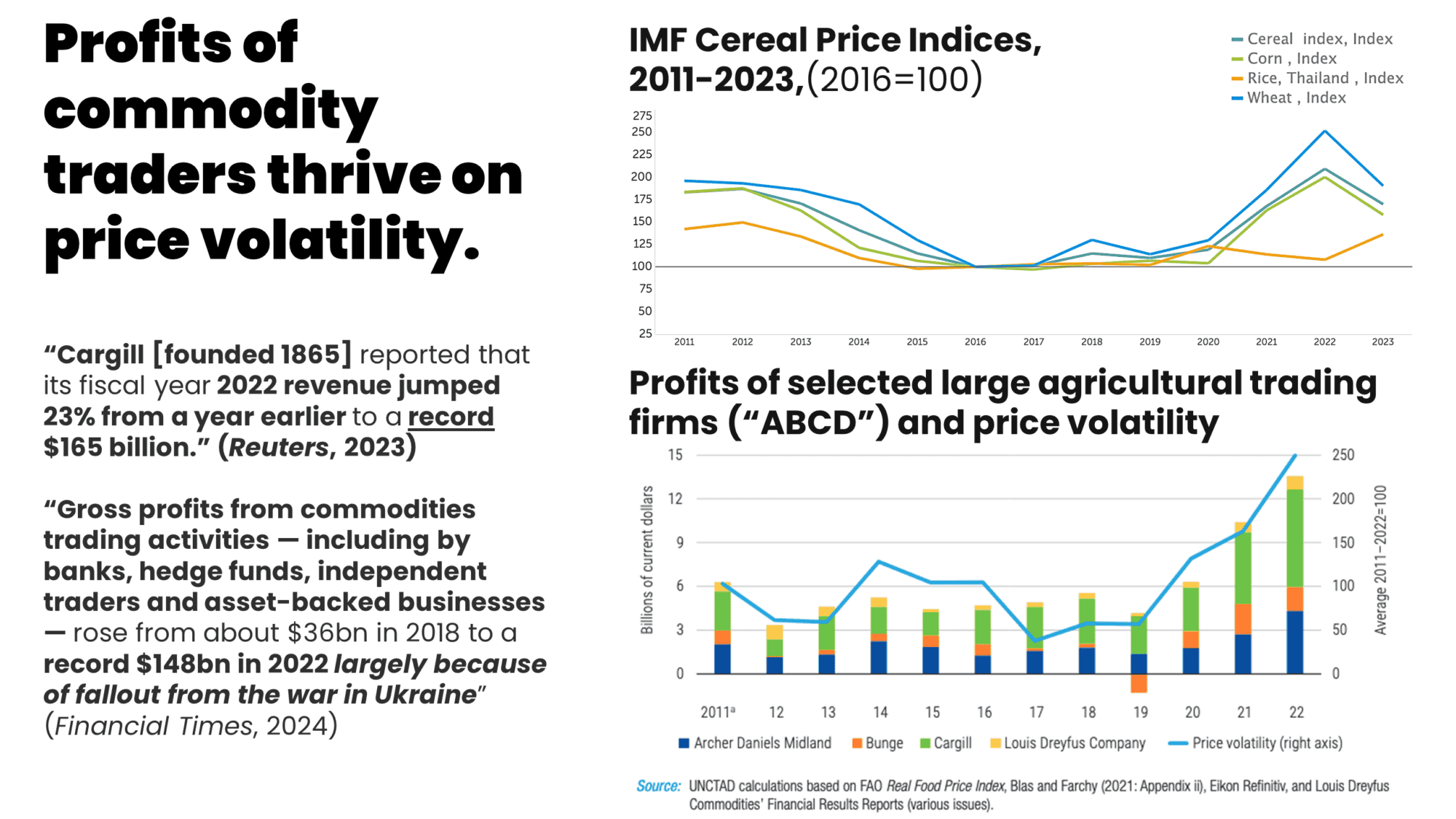

If we take another central sector, namely grain, we have a situation where, again, the grain prices on the top chart the cereal index of the IMF, where you have corn prices in green and rice prices in yellow – rice prices move quite differently for various reasons, and wheat prices in blue. You can see these indexes exploded from 2021 to 2022. You can also see on the bottom chart how the five companies that control 70% to 90% of global grain trade, the so called “ABCD” which stands for the first letters of the names of these agricultural trading companies, saw their profits increase very dramatically, not just with price increases, but also with an increase in price volatility. In other words, these are gigantic companies that have several hundreds of companies inside them that manage storage, shipping, information about agricultural yields, and even have “shadow banks” within them. They end up even betting against their own businesses in the future markets. These companies thrive on volatility. Of course, farmers don’t thrive on volatility, final consumers don’t thrive on volatility, but these gigantic companies do.

Cargill, for example, founded in 1865, reported that its fiscal year 2022 revenue jumped 23 percent from a year earlier to a record $165 billion USD. Since 1865, this company that has been controlling large parts of the global grain trade for a pretty long while, has never reaped profits of the kind that we have seen in 2022 And the list basically goes on.

This is not just about cargo; this is generally about commodity trading. So here’s the Financial Times saying, “Gross profits from commodities trading activities, including by banks, hedge funds, independent traders and asset backed businesses that have increasingly moved into commodity trading, rose from about $36 billion USD in 2018 to a record $148 billion USD in 2022, largely because of the fallout from the war in Ukraine.”

Of course, Cargill’s business is not just commodity trading; otherwise these numbers wouldn’t add up. But the point is that in commodity trading as a whole, you have seen absolute record profits, and you have seen an increased financialization of this sector, which means that these people thrive off the volatility in this market of essentials.

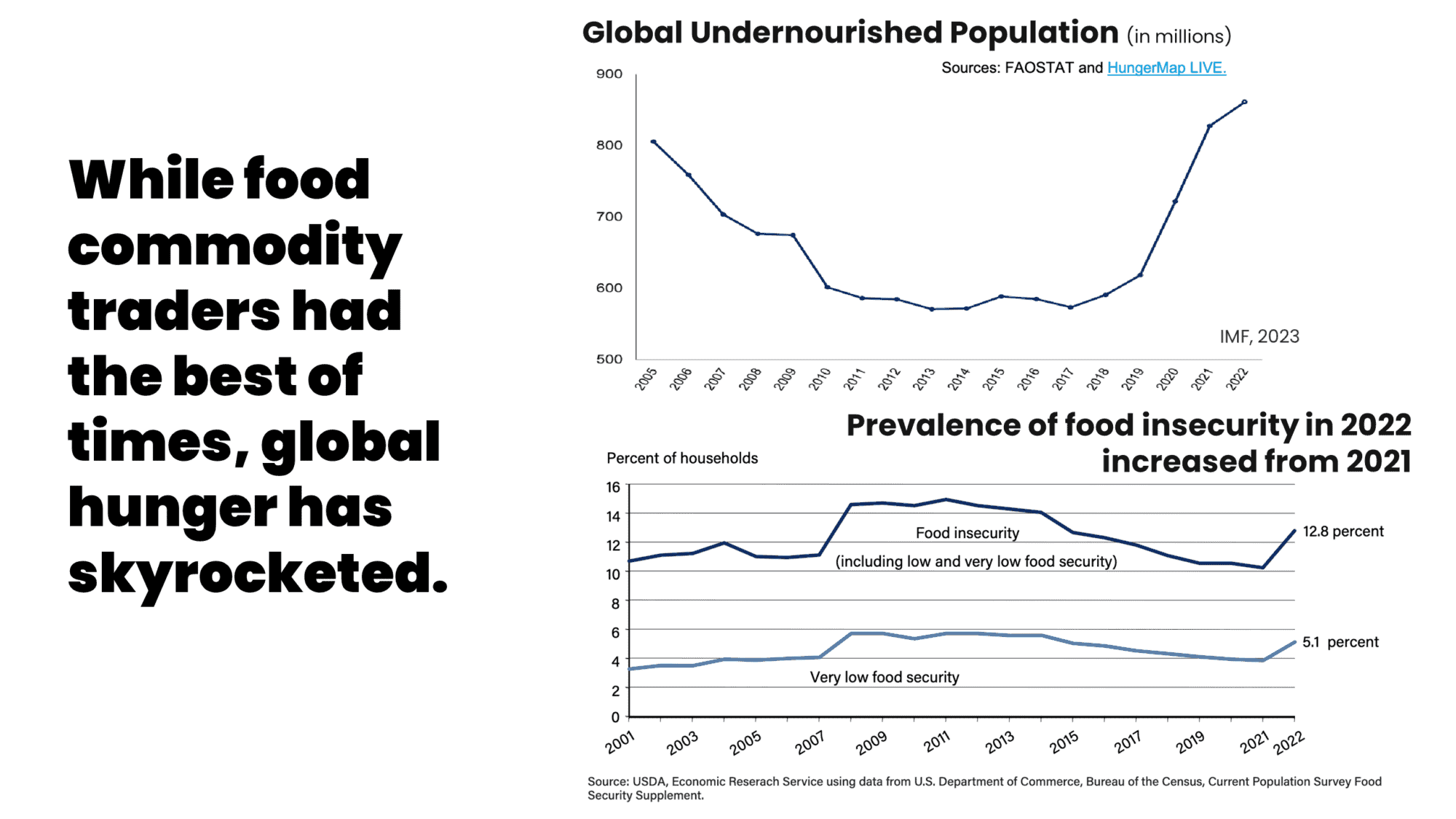

The flip side of this is not just inflation: if we are worried about food price inflation in countries as rich as Canada and the United States, we are talking about hunger in the rest of the world. On the top, you have a chart of the globally unnourished population based on estimates of the IMF. As you can see in 2004, there were around 800 million people around the world that were undernourished, and this is probably a relatively conservative estimate. This number in 2022 climbed to almost 900 million.

In other words, all the progress of eradicating hunger in the last 20 years has been erased in the span of just one year. On the flip side of this price explosion in an essential like grain. When I’m talking about survival, you might call me dramatic, you might call me exaggerated, you might call me an unreal economist standing in front of you in a bright yellow suit. That seems a little bit unserious. But I am actually pretty serious about this, because what I’m saying is that as long as these essentials are managed in the ways in which they are essentially managed right now, it is literally the survival of people at stake when we are dealing with major shocks. On the bottom chart, you can see food insecurity in the United States, and you can see that in 2022, even in a rich country like the United States, food insecurity picked up with inflation.

One last essential, and then I stop boring you with this, but I think it’s important: you will also have noticed that this is all totally unsophisticated. I’m just showing you screenshots from databases that you can Google and find online. And I’m doing it in this totally unsophisticated way, quite consciously, because I want to show that this is in plain sight. This is not something where you need to dig into fancy data that no one can find. This is not something that is out of reach for “ordinary people” — this is something that is literally headline news, where you just have to piece through and ask the questions that are actually pretty obvious, and dare to ask them and look for the information. And don’t feel embarrassed for not being sophisticated and not running fancy regressions in your presentation.

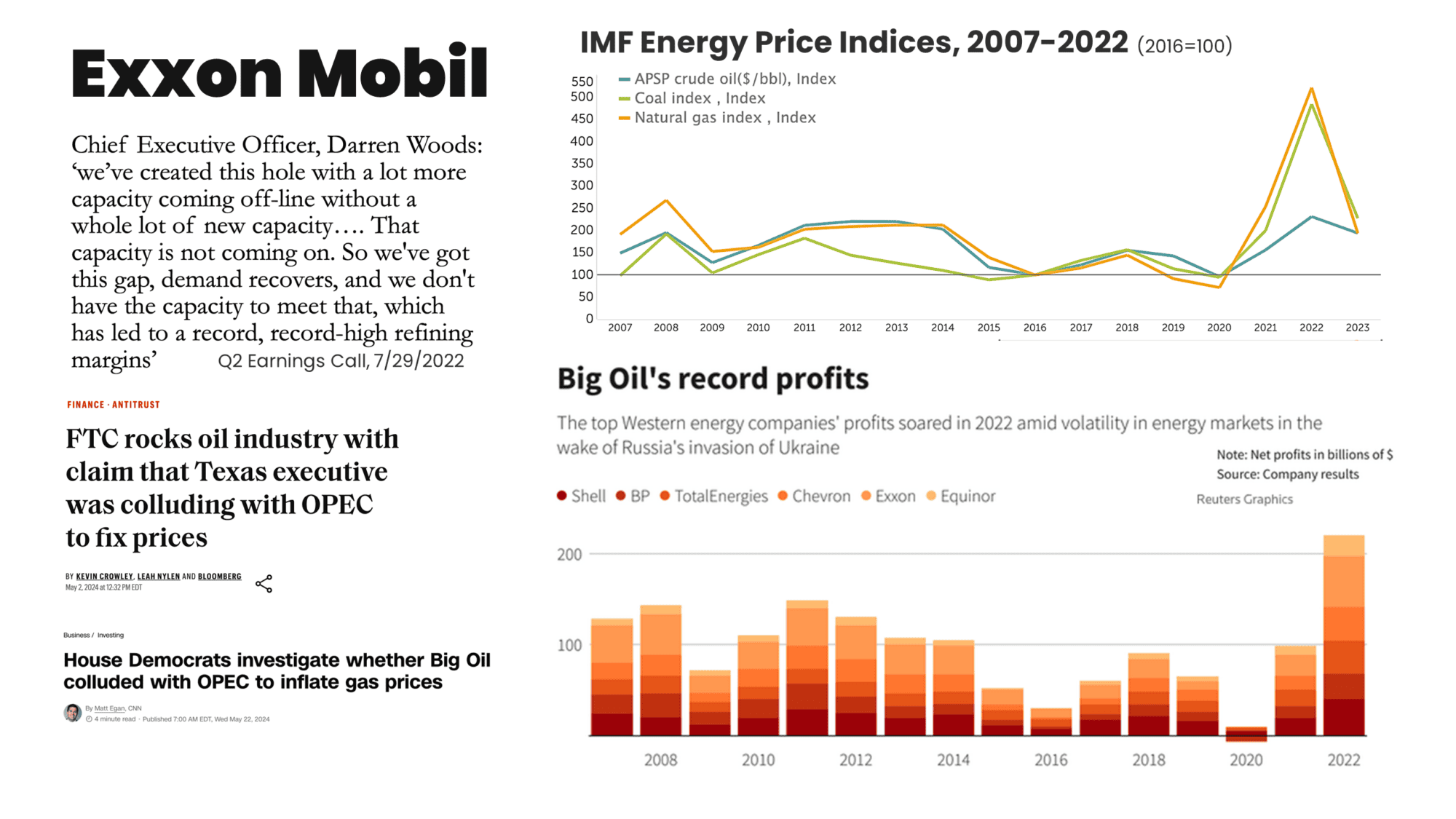

In the top chart, you see the prices of crude oil in blue, coal in green, and natural gas in yellow. And of course, there has also been a major explosion in 2022 of these prices. On the bottom chart, you can see the record profits of the world’s largest oil companies: Shell, BP, TotalEnergies, Chevron, Exxon, and Equinor. Now part of this was, of course, a windfall from the war in Ukraine, and part of it was also that in 2020 the demand for fossil fuels collapsed in a way in which it had never really collapsed ever. For the first time, oil prices went negative, as you might remember. In other words, this negative demand shock that happened as we were all hunkering down during the COVID pandemic resulted in a situation where you had a coordinated reduction in production; something that we have all been dreaming about in terms of fighting climate change.

It seemed impossible, but it happened. This is also something that would not have been possible if any one firm would have said, “Oh, Chevron, I’m now going to pump a little less oil,” then Exxon would have said, “Oh, wonderful, thank you very much. I’m now going to pump a little more oil and take your market share. Thank you very much.” This could not happen, but we instead had this coordination effect through the negative demand shock. When demand picked back up in 2021, the oil firms were in no rush to increase production, unsurprisingly, because what they found was that costs were down. When it came to capacity they had to shut down, where did they shut down? The highest cost capacity. If you have to call the shots, you’re going to shut down the highest cost capacity. So when demand picked back up, prices went up, costs were down, and they were finding themselves with record margins.

Or, in the words of the Chief Executive of ExxonMobil, Darren Woods, during the second quarter earnings call of 2022, “we have created this hole with a lot more capacity coming offline, without a whole lot of new capacity. That capacity is not coming on so we’ve got this gap, demand recovers and we don’t have the capacity to meet that because we have created that hole which has led torecord high refining margins.”

This is not me spreading conspiracy theories. This is what corporate earnings calls tell us when we read them. This is what people are saying on record to their investors. In fact, in recent weeks, the US Federal Trade Commission has picked up on that, and is now looking into a possible collusion with Organization of the Petroleum Exporting Countries (OPEC) around fixing prices in 2020 and around the actual reduction in production. Also in the US, the House Democrats have started investigating whether big oil colluded with OPEC to inflate gas prices in 2020. But even without these investigations, this has been basically in plain sight from the earnings calls.

Moving from essentials, you probably expected a lecture about inflation. You’re like, “why is she talking about these specific firms and global hunger?” Moving from essentials to inflation, I’m puzzling you even more by showing you a picture of a coin-powered horse. And I would argue that the pre-pandemic way of thinking about inflation was basically similar to the workings of this coin-powered horse. I think one key feature of this horse is that it’s one dimensional: it rocks back and forth, and that’s it. Another key feature is that we can know exactly by how much it is going to the front, and how much it’s going to the back, and what the mechanism is that holds the movement of this horse within this precise bandwidth.

We are in a one-dimensional world. We know exactly what the variables are that we need to manipulate to keep things within the desired band, which is kind of what monetary policy was supposed to be. It was supposed to keep the interest rate on target with basically one policy lever, assuming that inflation originated on the macroeconomic level, being basically macroeconomic in origin, to macroeconomic in outcome, one-dimensional and, as such, could also be controlled with one lever.

I think this way of thinking about inflation, unfortunately, was slightly simplistic. And, of course, my portrayal was also simple to be fair. But, I think this thinking has failed us in the context of the pandemic. In fact, what underpinned this understanding was still the spirit of Milton Friedman as he, for example, expressed in 1974, where he said responding to people that pointed to the prices of oil and food as drivers of inflation:

“What of oil and food to which every government official has pointed? Are they note the obvious immediate cause of the price explosion? Not at all. It is essential to distinguish changes in relative prices form changes in absolute prices. The special conditions that drove up the prices of oil and food required purchasers to spend more on them, leaving less to spend on other items. Did that not force other prices to go down or to rise less rapidly than otherwise? Why should the average level of all prices be affected significantly by changes in the prices of some things relative to others?”

Milton Friedman, 1974

One thing that I want to note from the introduction: it was pointed out that we need an explanation of inflation that people can actually understand. The implicit attack here is on ordinary people’s understanding of inflation: “You just don’t get it. You look at oil and food, but, sorry, you just don’t get it. You need an economist in the room to explain to you.” It’s the implicit undertone here, I would argue, that has already been replaced with a new kind of commonsense in the last year-and-a-half where we now, I think, have a number of papers demonstrating the contrary by very established, very mainstream economists.

If you want to make sense of inflation today use this language: “Economists show that supply shocks and bottlenecks mattered for the return of inflation.”

In other words, changes in relative prices were absolutely essential for the return of inflation. What we do not have a good sense of, however, is that if we are living in such a world of emergencies, if we are living in a world where more shocks are going to come, what are the shocks that we should be worried about? What if we look back to the financial crisis, and what we did after the financial crisis, where we started to run stress tests on banks? If we want to run stress tests on our economy today, what are the sectors, what are the prices, that present points of vulnerability for monetary stability?

Speaking with a German accent, I feel I can make this rather morbid comparison. Input-output modeling was first applied during the Second World War in US strategic bombing, when they were asking the questions: What are the targets in the enemy’s economy that are the points of vulnerability? That when we hit these points, will it create a blast to the enemy’s economy that is disproportionate to the damage done locally? For that, they used network analysis to identify these neuralgic points.

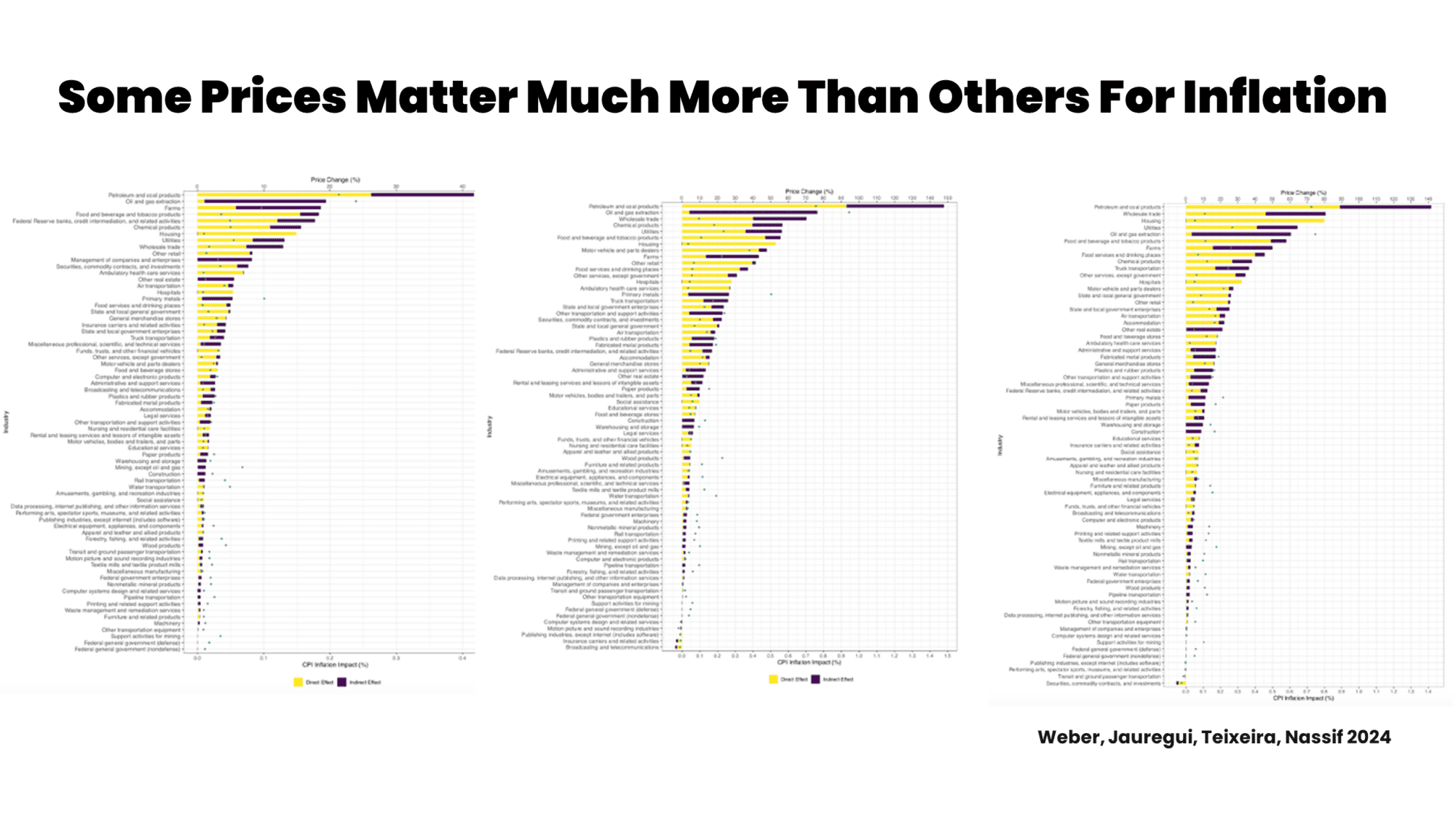

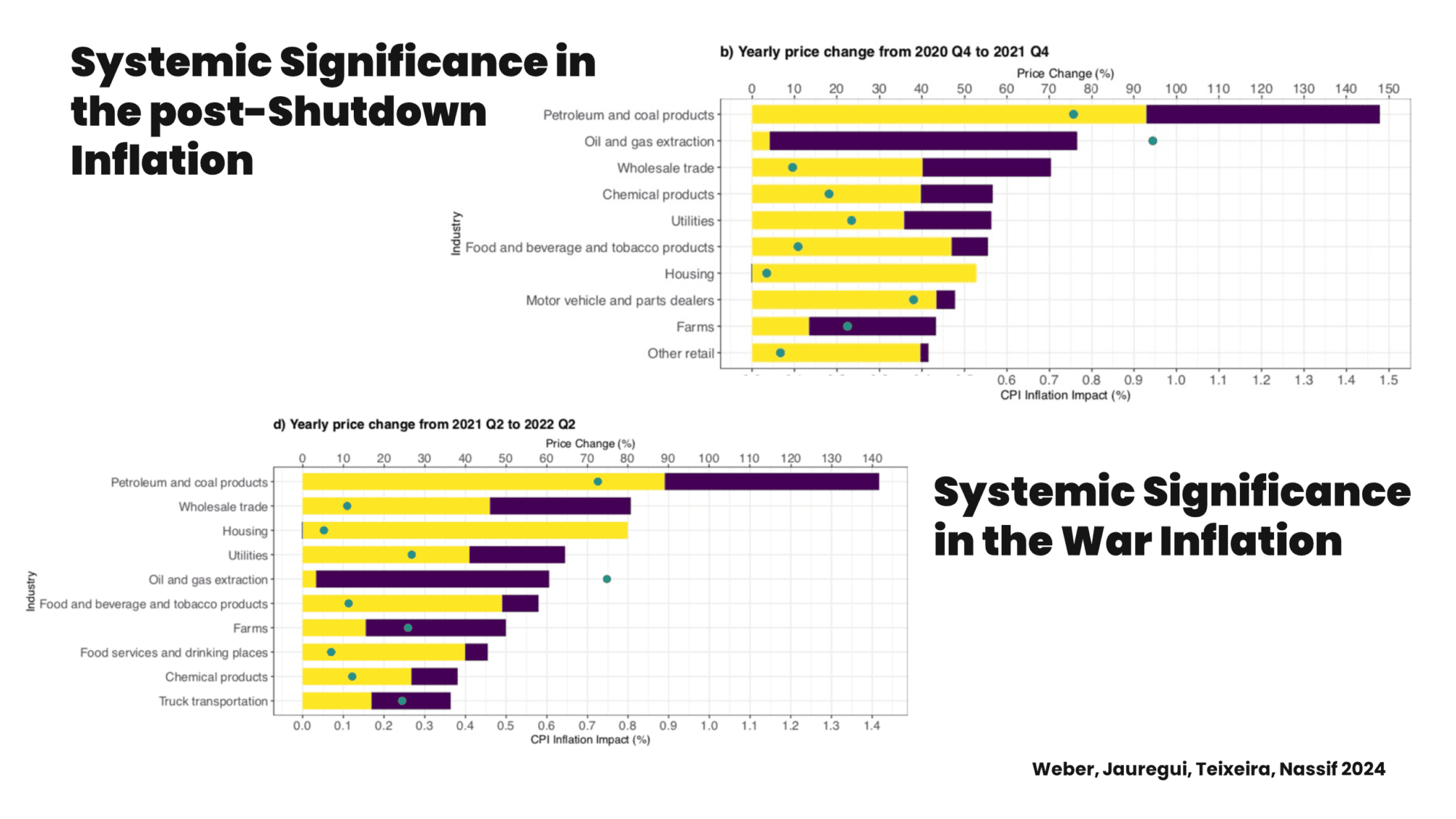

What we have been doing in our research is to try to identify what are these points of vulnerability if we look at inflation. We have been running simulations, and I illustrate this based on the next chart that I’m pretty sure that no one can read. Each of these bars represents a sector, and each of these bars has two colors: yellow and purple. What we have done is we have “shocked” each of the economic sectors in this input-output network with a price increase, and so, we have simulated what happens if prices increase in that sector by a certain amount. We then do this to the next sector, and the next sector, and the next sector.

Through this simulation, we see a direct effect because when the price of food goes up, inflation goes up because the price in the Consumer Price Index goes up. We also see an indirect effect because the input prices for restaurants go up, and hence an indirect effect on cue.

On the left hand side, we have used price changes based on the price volatility before the pandemic in the United States. In the middle chart, we have used the actual price increases in the fourth quarter of 2021 – just at the time when we moved out of the pandemic shutdowns. And on the right hand side, we have used the price increase in the second quarter of 2022 – just at the onset of the Ukraine war.

What we can see is that the prices of some sectors matter much more than the prices of others. There’s nothing in here in the way in which we have modeled this that would have given us the shape of these bar charts. But we can see that there’s a handful of sectors that have a very large inflation impact, and all the other sectors don’t matter as much.

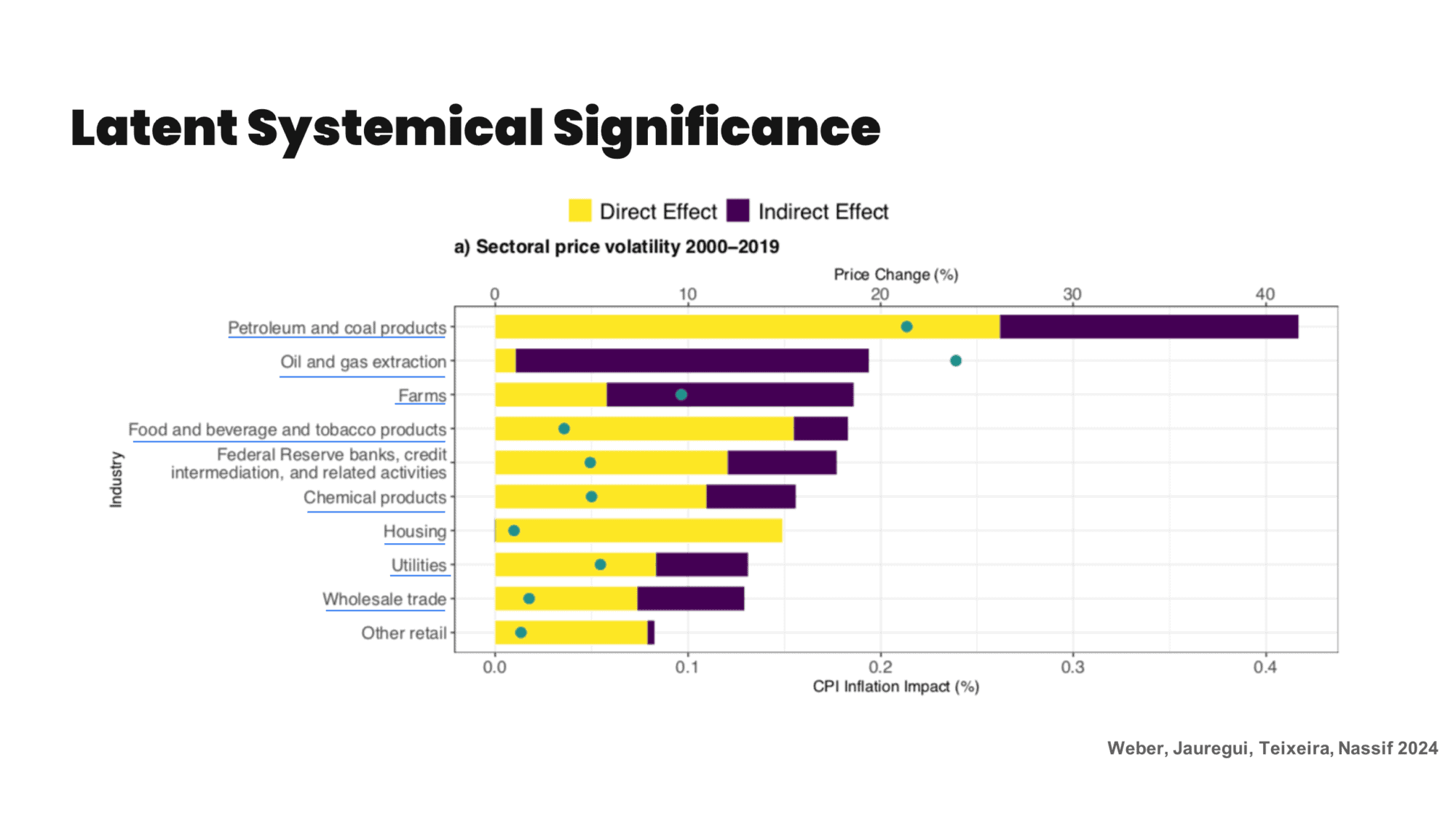

If we zoom in to look at what these sectors actually are, we find that they are petroleum and coal products, oil and gas extraction, farms, food and beverage and tobacco products, chemical products, housing, utilities, and wholesale trade. Now, this is using the pre-crisis price volatility. You’ll have noticed that I’ve skipped over the Federal Reserve. Of course, I’m not of the opinion that the Federal Reserve is not systemically significant. In other words, I am absolutely of the opinion that the Federal Reserve is systemically significant. In fact, I would argue that currently we have an inflation fighting regime that relies on manipulating the price of only one systemically significant sector, namely money.

In other words, we try to manage the whole inflation problem by focusing on only the interest rate, only the price of money, whereas I would argue that there’s a range of other systemically significant prices that we should also be paying attention to if we want to achieve greater price stability, which I think is important.

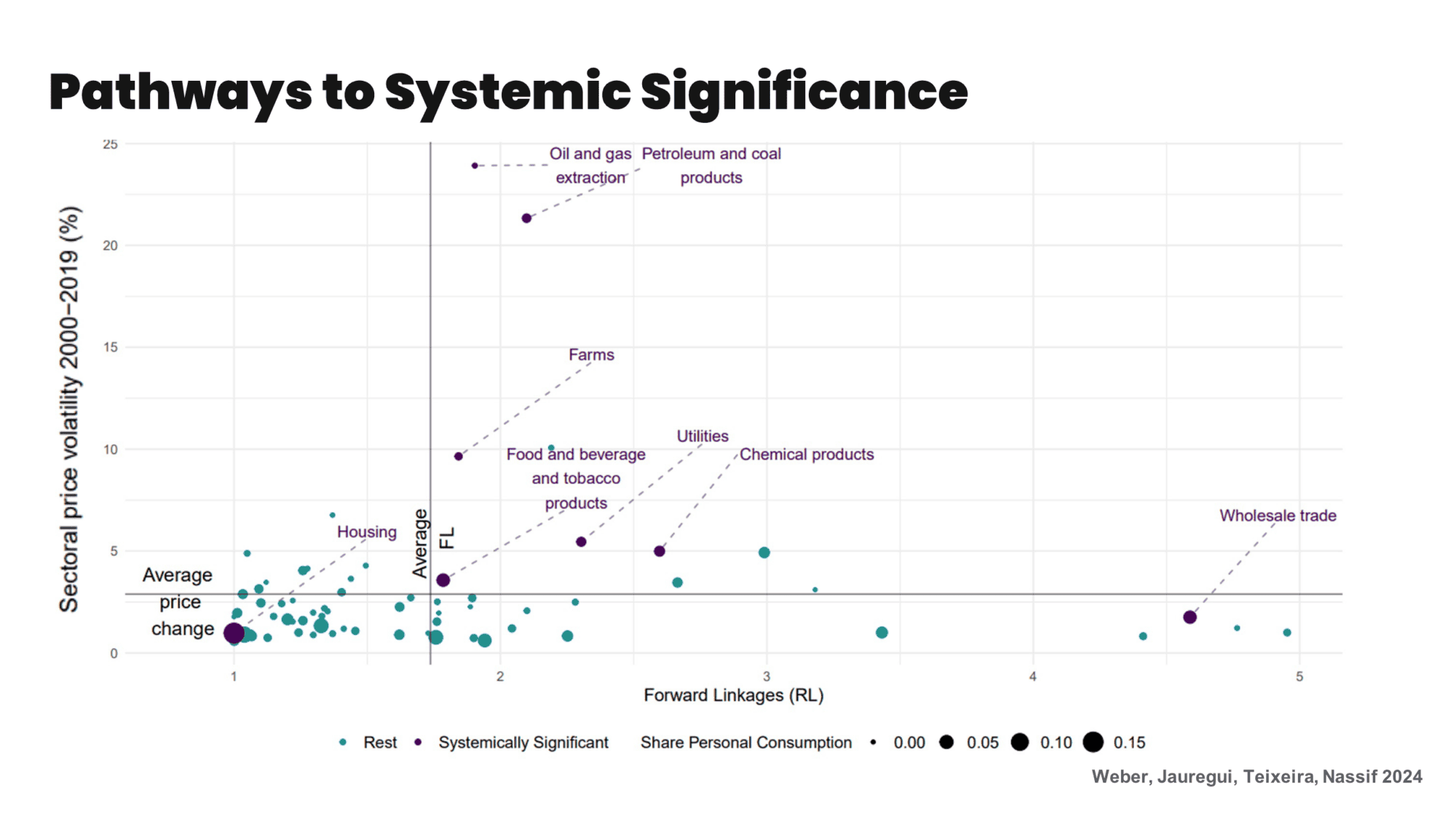

If we do the same exercise for the fourth quarter of 2021 and the second quarter of 2022, we basically get the exact same influential sectors that I named before, with one exception here, which is truck transportation, reflecting the whole trucker shortage in the United States that rendered this sector having a higher inflation impact. If we ask ourselves, what are the pathways to systemic significance in this kind of framework, it’s basically three dimensions.

The first one is the weight in the CPI, the weight in the consumption basket, or, to put this into more common language, the importance of a good for people’s consumption and livelihoods.

The second dimension is the forward linkages, which we have here on the horizontal axis, or in other words, the importance of a sector to the production of all other sectors.

And the third dimension is price volatility. Or in other words, the tendency of prices to move, since not all prices move by the same amount, because they all have different markets, different dimensions, different dynamics.

If we think about this more intuitively, this is basically saying that the essentials for inflation fall into three groups. They are about the essentials for human livelihoods, essentials for production, and also essential for circulation and commerce, such as wholesale trade. This includes all the kind of commercial infrastructure that you need to move stuff around, which also includes maritime shipping.

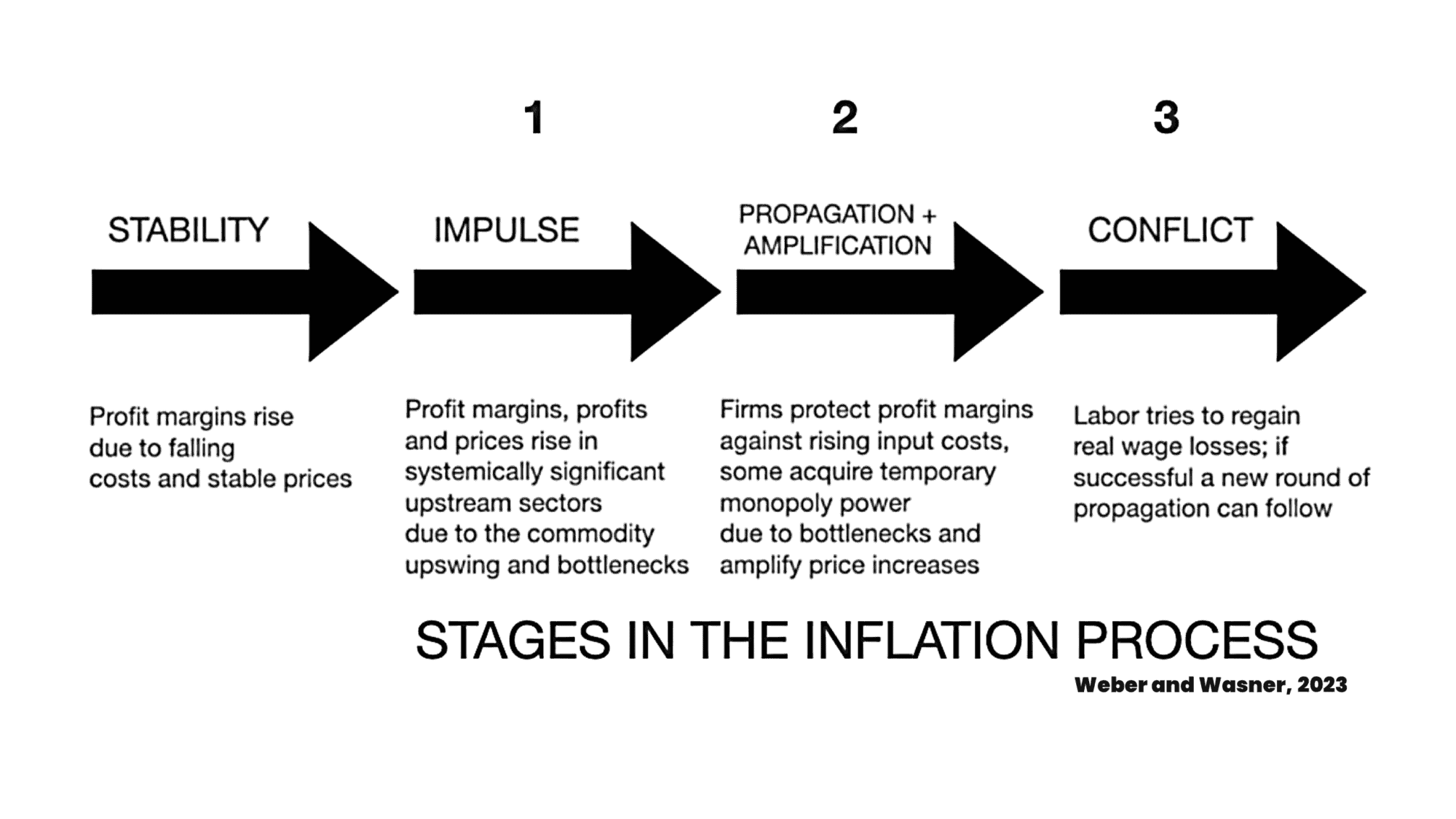

Moving from this analysis of what are the sensitive points to putting this together into an actual analysis of inflation, is what we did in the sellers’ inflation paper, where we were arguing there are three stages in the inflation process. Coming out of a situation of price stability, we already had incredibly high levels of corporate concentration and we already had incredibly high levels of market power. We already had very greedy corporations, if you want to use this morally loaded language — which maybe we want for political reasons, maybe we don’t want for analytical reasons — but in any case, corporations were already profit-seeking and greedy before. But prices were very stable. So what is it that happened that turned the situation of stability into a situation of instability?

What we are arguing is that this has been set off by shocks to the essential sectors that we just identified. But if you had just these shocks, then you would have also had local price explosions. And maybe we could have said, “Oh, it’s transitory, we can lean back and wait.” I still don’t think so, because we are talking about essentials, and the price of food matters to people so much that saying we lean back and wait is not a great solution.

What did happen was that these local price shocks were turned into generalized inflation through a process of “sellers’ inflation,” where firms that were confronted with these cost increases did not absorb these cost increases, but instead responded to these shocks by pricing to protect their profit margins. Up to this point, we have a situation where the majority of people would have seen an erosion of their purchasing power. They are faced with firms that protected their margins, but meanwhile people have lost purchasing power. Eventually, people will fight back and will ask for higher wages, at which point you can enter into a conflict stage of sellers’ inflation.

However, the wage catch up here is a result of this inflation, and not the origin of inflation. This is the desperate attempt of working people to regain their living standards; not the beginning, not the origin, not the thing that kicked off inflation to focus at the sellers’ inflation stage. I think to understand this, we have to emphasize that these cost shocks function as coordinating mechanisms for firms, even in very highly concentrated firms.

If you have, let’s say, three firms that control a whole sector, it’s difficult for them to start increasing prices without being sure that the other firms are also increasing prices. If you start increasing price, let’s say, you are Honda and I am Toyota, and Honda starts increasing prices, then Toyota says:

“Oh, thank you very much. I will take your market share because I am in command of one of the most efficient, global, powerful production networks that has ever existed in the car sector, as are you, my friend Honda. But since you chose to increase prices, you lost your market share. I could just ramp up my production overnight because I have all these different firms around the world, all these plants across the whole planet that I can mobilize very quickly.”

Obviously, this is totally stupid and in this kind of situation, no one is doing this. This is why we see, even in incredibly concentrated sectors, firms keep prices stable in stable times. However, if there is a shock that sends a very clear sense of signal to everybody in this sector that costs have gone up and now everybody’s going to price to protect margins, then this fear of another firm taking your market share is no longer there because the cost structure itself has coordinated the pricing behavior.

If on top of this, there’s also a shortage; let’s say, I’m still Toyota and you are Honda. We both rely on computer chips and there’s a computer chip shortage, as I think has happened at some point in recent history, then this means that suddenly we both know of one another, that we can only produce as many cars as we have computer chips. All the competition over market share is gone because you have your market share frozen by the number of computer chips that you have. I have my market share frozen by the number of computer chips that I have. And now we can start hiking prices in ways as if we were each a monopolist, which means that we can hike prices in ways that increase profit margins.

I would argue that this temporary monopoly story is an important story, but it’s not the general story. The general story is the one of cost shocks, and cost shocks coordinating price hikes, which is why I am so worried about the overlapping emergencies, and why I started this lecture with these shocks.

I encourage everybody to read earnings call. In fact, I think that no one should graduate with a degree in economics without ever having read an earnings call, because this is the best lesson you can get on how corporate leaders are thinking about business strategy and how they are communicating to the people that they want to convince to give them money, which is pretty high stakes conversation for them.

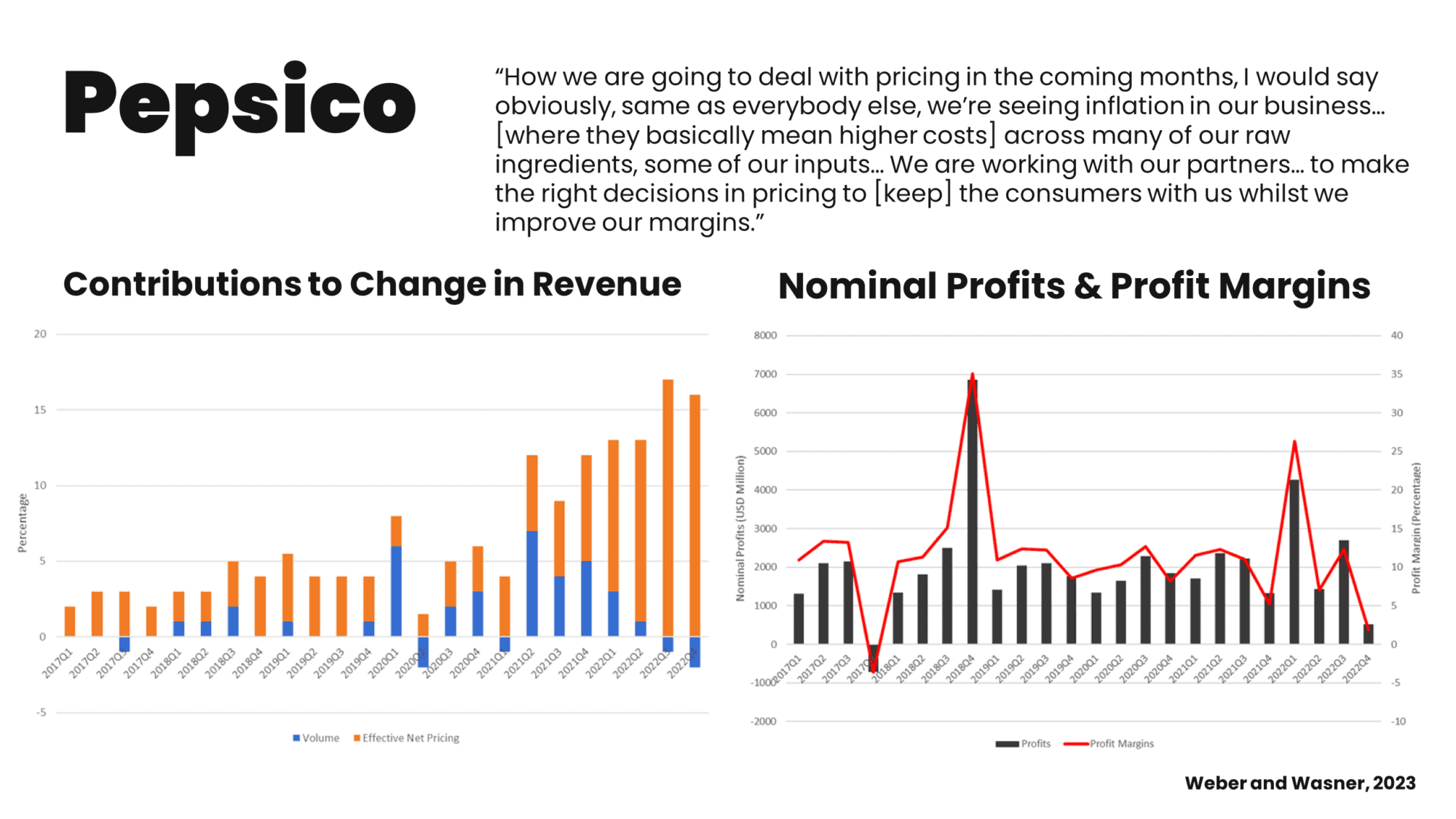

For example, Pepsi, talking about how they are going to deal with cost shocks:

“How we are going to deal with pricing in the coming months, I would say obviously, same as everybody else, we’re seeing inflation in our business… [where they basically mean higher costs] across many of our raw ingredients, some of our inputs… We are working with our partners… to make the right decisions in pricing to [keep] the consumers with us whilst we improve our margins.”

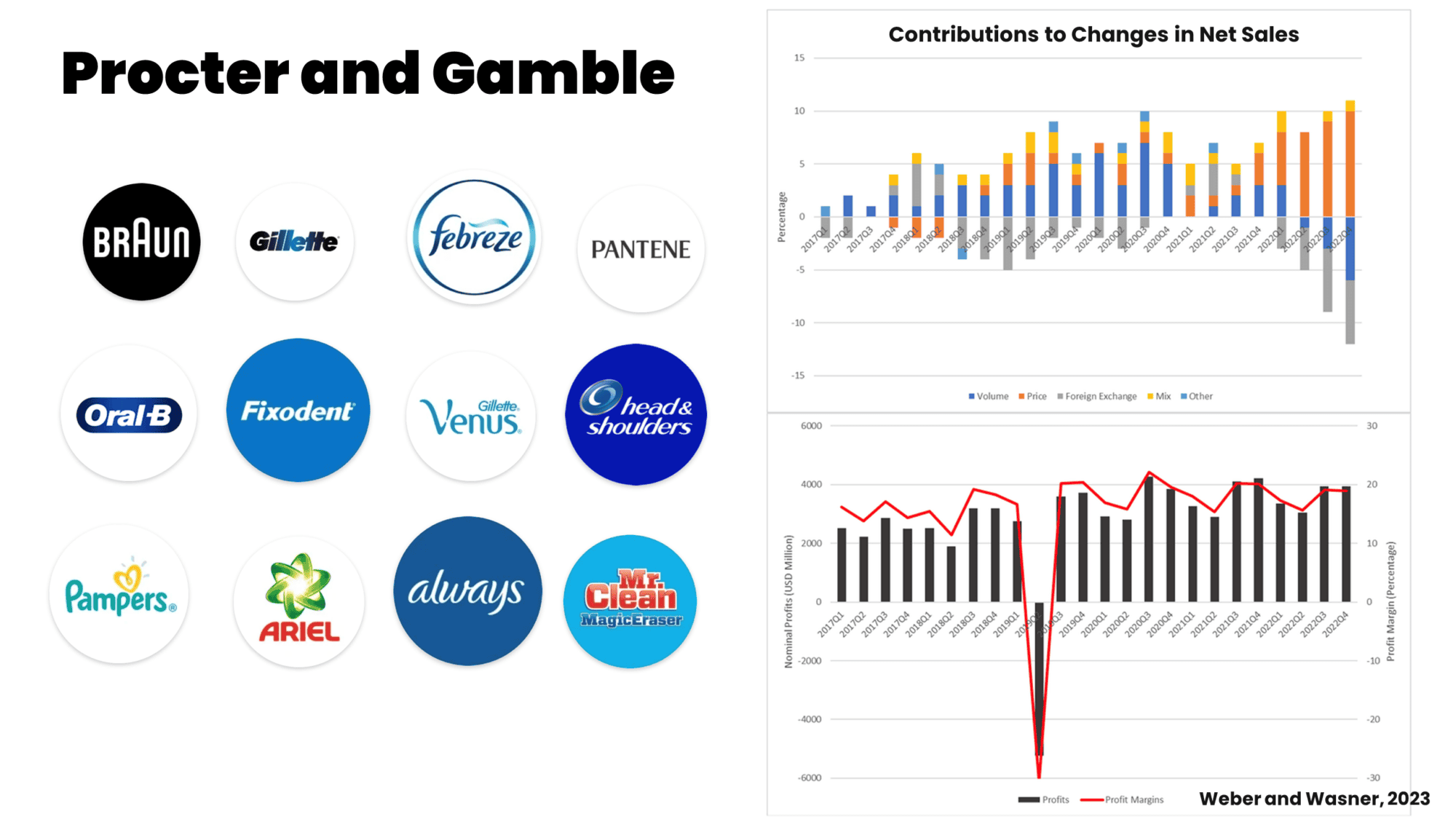

From the left chart, you can see in orange the price increases, and in blue the volume increases. You can see that even when volumes were declining, prices were still increasing by a lot. In other words, this is not a situation where demand is picking up, where people are asking for more, but then they start increasing prices. This is a situation where demand is actually going down, volumes are going down, and prices are going up.

You can also see on the right chart, the profit margins illustrated by the red line. And you can see that while they did pretty well; they basically protected their margins rather than increase them. When they were bragging about increasing margins, what they basically achieved is margin protection.

Another example is Procter and Gamble, where they are saying:

“We are better positioned for dealing with an inflationary environment… than we have ever been been before, starting with a portfolio that is… focused on daily use categories, health, hygiene and cleaning, that are essential to the consumer, versus discretionary categories which in these environments are the first ones to lose focus from the consumer.”

In other words, this idea of focusing on essentials, on stuff where demand is very inelastic, is part of the portfolio strategy of a company like Procter and Gamble. If a firm protects its margins, it by definition is a basic matter of accounting.

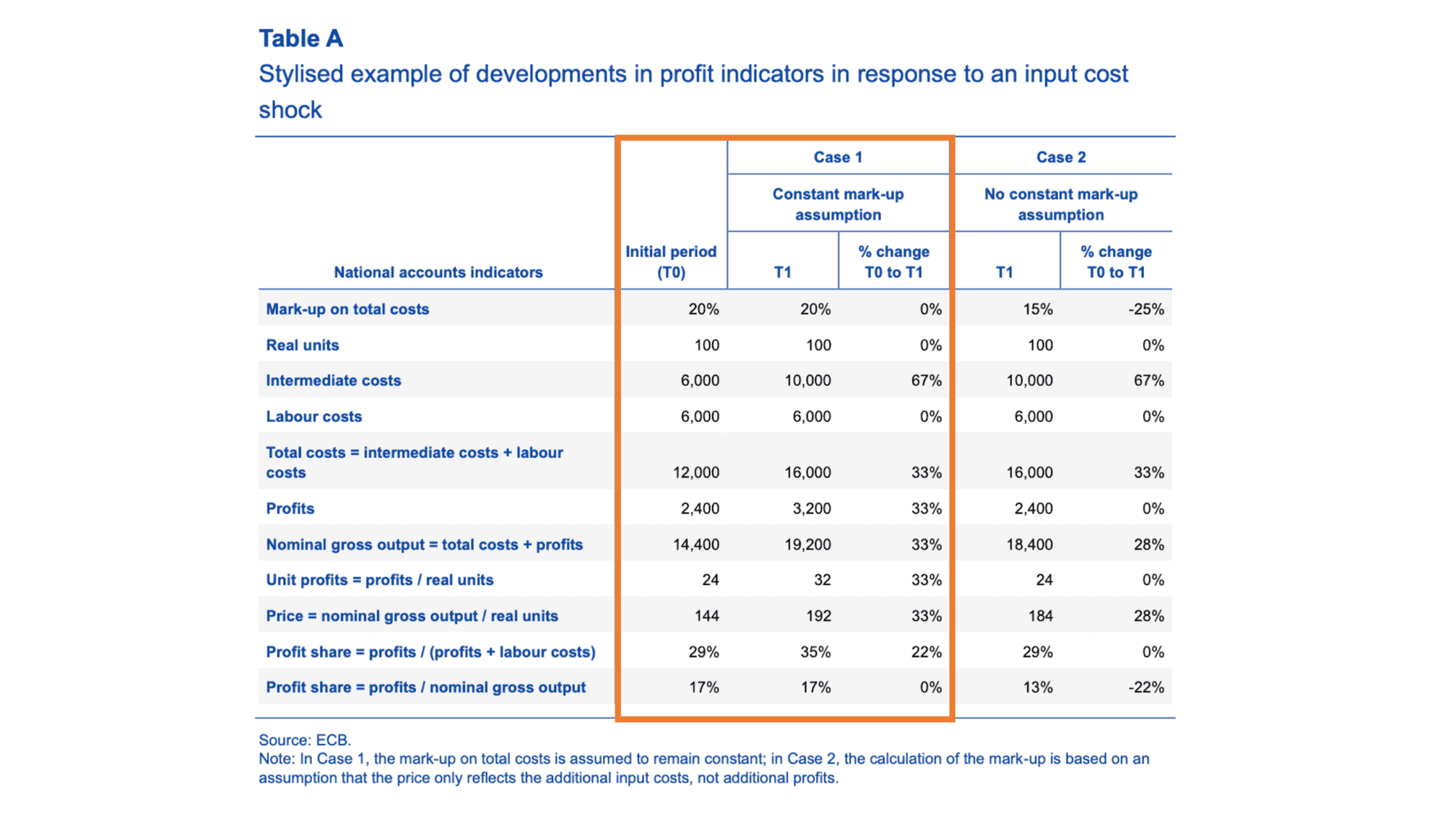

Here is a chart from the European Central Bank that shows that this is basically a matter of accounting. If profit margins stay constant in response to increases in costs, this means that profits go up. This is like when you buy a cheap house and you pay a 3 percent agency fee to your broker, or you buy an expensive house and you pay 3 percent agency fee to your broker, then one was a high cost, the other was a low cost. In one case, the profits of the broker will be much larger than the other, but the percentage stays the same. This is the exact same mechanic behind why protecting margins results in increased profits.

All of what I’ve shown you so far is very pedestrian, but I also want to make the point that if you want to understand economic phenomena in real time, you need to work with the data that you have. Corporate earnings calls are one of the data points that you can use in real time, even if they are not as “systematic” as economic indicators, but again, this goes back to the point of empowering “ordinary people” to think about inflation. This is the kind of data that everybody can read that is publicly available and that is coming out in real time.

There has also been a certain demand side to this, where I would argue that prices are not just a point in a supply and demand diagram but, at the end of the day, prices are a social relationship between firms and their customers. I would argue that firms in their pricing strategies manage this like a social relationship where they look at how much price they can take without disturbing the customers in ways that end the relationship because they feel cheated.

If you watch television, you see retail business groups warn of catastrophic supply chain disruptions. You see this kind of news every time you turn on your TV, which was especially the case during the height of the pandemic, and you then go to the grocery store and you find that the stuff that you are buying is suddenly 20 percent more expensive than it used to be. You go like, “Oh, yeah, makes sense. Obviously, there have been all these massive disruptions. There are supply chain issues. Things are getting more expensive because there’s a shortage.” This legitimacy on the part of what customers are willing to pay, I think, is an important part of this equation, and it’s what Tracy Alloway, Managing Editor at Bloomberg, has been dubbing “excuseflation.”

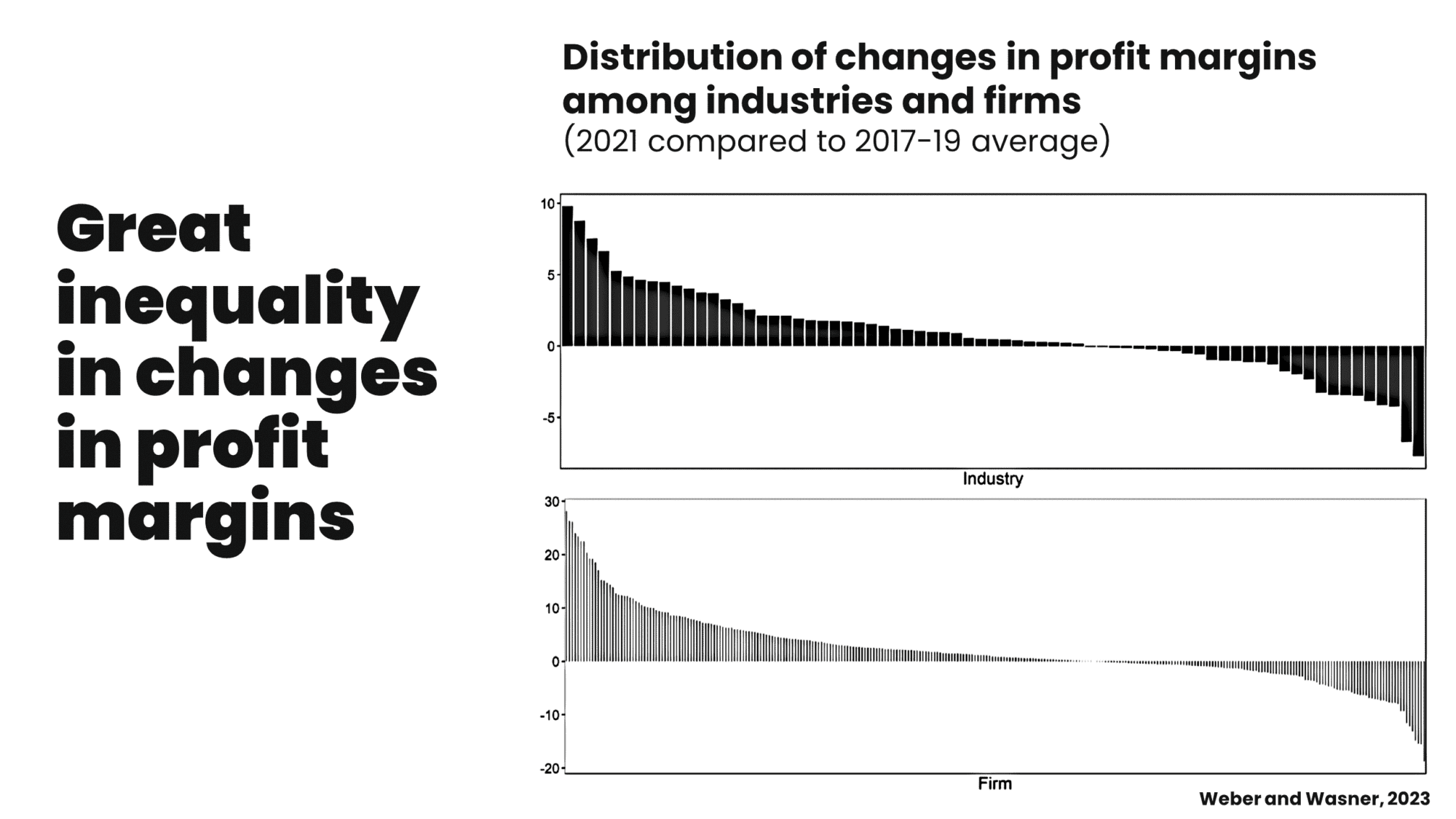

Of course, not all firms benefited from this. Here you can see changes in profit margins from 2021 compared to the 2017-2019 average at the industry level in the top chart, and the firm level in the bottom chart. We can see that about two-thirds or so of these firms profited from these shocks, and about one-third or so lost. There are now some papers that have come out that have suggested that firms that had more market power before these economic shocks happened benefited more than firms that had less.

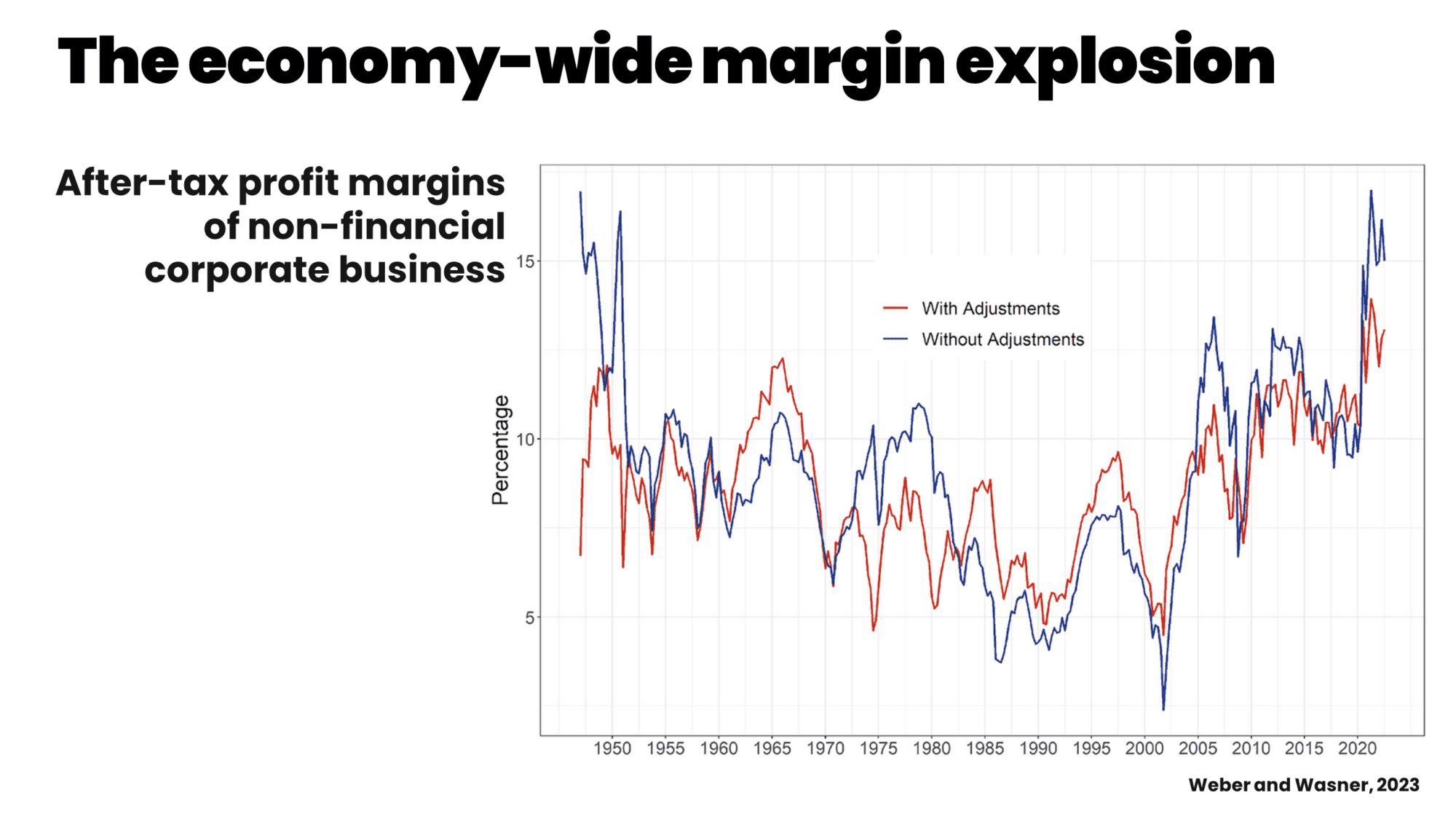

If we put together profit explosions in these essential sectors and margin protection as a general trend across the economy, then we get a margin increase. And, in fact, this here is a chart of non-financial corporate business margins in the United States from 1947 to 2023 where you can see this almost vertical line from 2020 to 2021. This was precisely the moment when I wrote that article in The Guardian because I was watching the profit margin news and I was seeing these margins explode at that time. I was looking at the long chart and I saw that nothing like it had happened since the transition from the Second World War. I had studied the transition from the Second World War in my book, How China Escaped Shock Therapy, which had a whole chapter on that transition and the challenge of inflation at the time. This is how I came to understand that economists at the time, from across all sorts of schools of thought, at this moment of transition and post-war profit explosion, argued for a sectorally tied and targeted intervention, arguing for price controls.

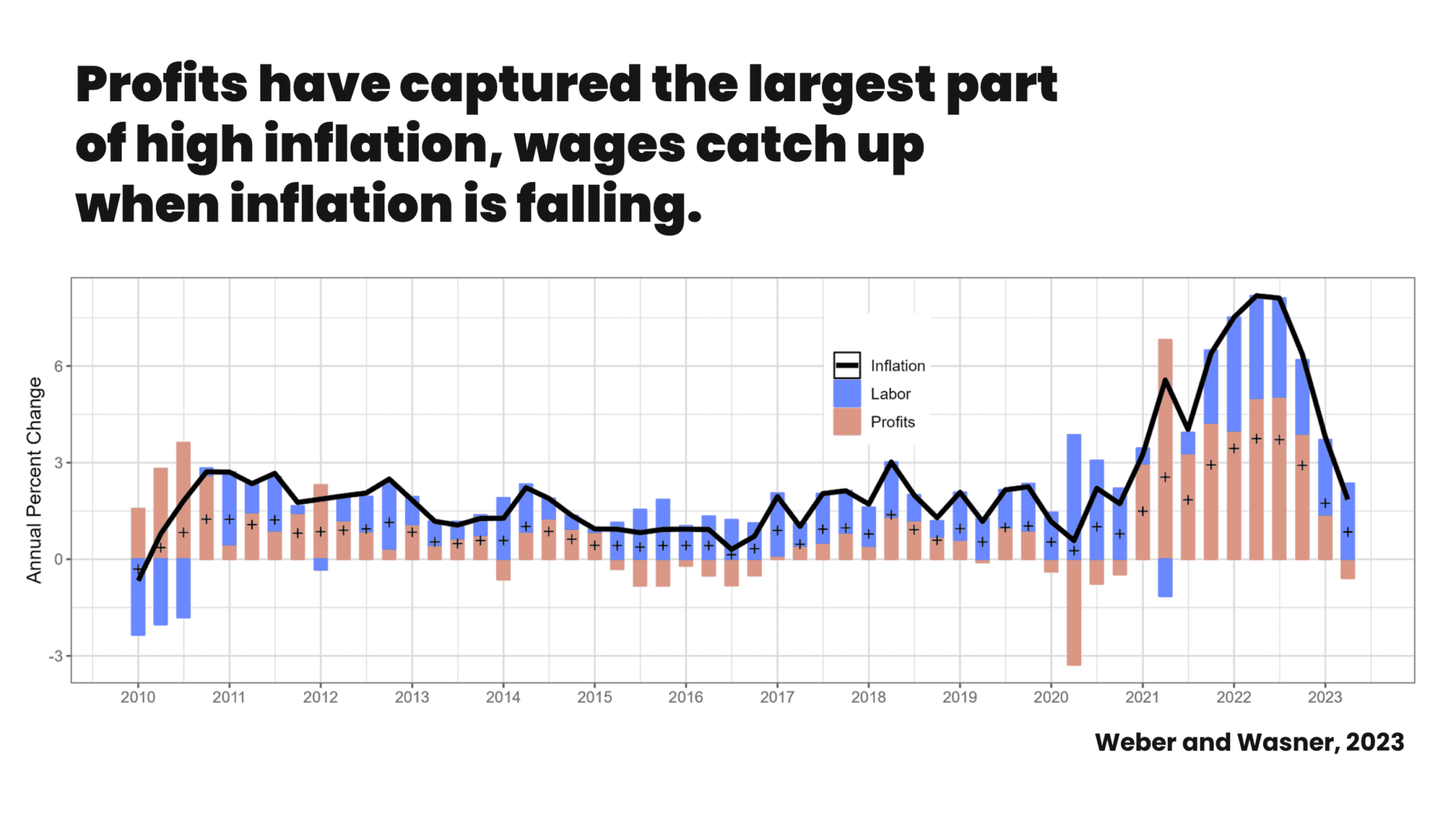

If we come to the conflict stage and we look at the distribution of inflation between profits and wages, you can see in the above chart, with profits in orange and labor wage share in the GDP deflator in inflation in blue, that the wage share increases when inflation is going down. It is true that in more recent financial quarters in the US, wages have been accounting for larger shares of inflation, but at a time when inflation was trending downward. This is perfectly consistent with what we have been arguing from day one: that eventually wages will have to catch up because people will not accept a permanent decline in living conditions.

To conclude, I want to start by recapping why I think the old stabilization paradigm fails the many. Monetary and fiscal austerity is meant to cool down the economy and push down wages, but wage increases are a consequence of sellers’ inflation and demand changed more in composition than in levels. It’s true that there have been demand spikes in certain levels, but the composition change was much larger than the level change. The idea of imposing austerity is to push down the level.

Preventing wage catch up cements the redistribution from the bottom to the top that sellers’ inflation brings about.

Macroeconomic tightening kicks in when inflation is already generalized at the third stage of this inflation process, and comes at a high economic and, I would like to add, political cost.

We have many very thorough empirical studies that show the link between austerity and the rise of right wing parties. At a time where our democracies are as fragile as they have ever been in a long time, we have to take this seriously, and we have to understand the political consequences of fighting inflation with austerity as a serious concern from a progressive perspective, in addition to all the other economic reasons.

Credit tightening also affects smaller firms much more than larger ones, since larger firms are more credit-worthy than smaller ones, and can in fact increase corporate concentration. It also exacerbates the affordability crisis in housing, one of the essential sectors that has been a driver of inflation, while generating yet another round of windfall profits for banks that have been very fast in passing on the interest rate increase to those people who hold a mortgage, and very slow in passing on the interest rate increase to those people who have savings accounts.

Addressing climate change requires large scale investments and popular support. I think the popular support part has often been underestimated, but it’s absolutely critical. Both are undermined by austerity.

Debt and exchange rate crises in the Global South are accepted in this present “stabilization paradigm” as collateral damage for the stabilization of rich countries.

That’s why I think we need a new paradigm.

Corporations in systemically significant sectors are “too-essential-to-fail,” just like banks have been too-big-to-fail, so we need to apply the exact same logic to essential sectors. That is, in fact, what I am developing in my forthcoming book. Cost shocks and supply constraints can limit competition and coordinate price hikes, and thus increase profits.

In other words, competition fails to control prices in these situations of emergencies. While during normal times competition can control prices, more shocks are coming in our times of overlapping emergencies. If the worst of times for most people are the best of times for companies, economic resilience is out of reach.

We need an inflation fighting toolbox that buffers against supply shocks in essential sectors, prevents price explosions, and contains sellers’ inflation while enabling a green transition.

Some key instruments for such a toolbox can be price monitoring in all early warning systems for essentials, because we should be paying attention since timing is of the essence.

As I can tell you from the experience that we had in Germany during the energy crisis, we need virtual and physical buffer stocks for essentials, ideally on different geographical levels of organization, not only to stabilize prices, but also to use them as strategic tools for public procurement, in order to encourage a green transformation.

We need emergency price caps to prevent price explosions in essentials, when we do not have instruments to adjust supply, and make supply more resilient.

We need windfall profit taxes and price gouging legislation to prevent these price spikes from rippling through the whole economy.

We need strict regulation, de-financialization, antitrust, resilience, and transformation standards for essentials.

And of course, we need public investment in resilience and transformation of essentials. Transformation, at the end of the day, is focused on the big challenges: how to transform the essentials.

Thank you very much.