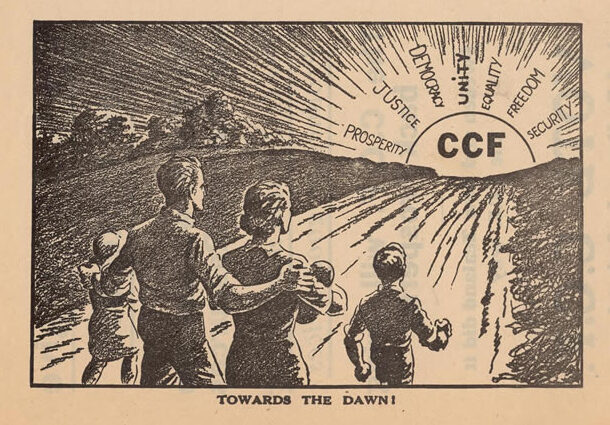

In his novel, The Lost Cause, Cory Doctorow imagines an America where progressive legislators have passed a transformational Green New Deal. Cities are being rebuilt on a massive scale, housing-dense and climate-resilient; jobs are guaranteed to all who want to work; clean energy is everywhere. Although the story is set in the near future, Doctorow’s world feels far away. Part of what makes it feel so distant is that Doctorow’s characters have a clear vision of the society they want to live in. By contrast, as Andrew Jackson wrote in his 2017 survey of Canadian social democracy, contemporary social democrats have “defended past social gains […] but have largely failed to develop a fully convincing contemporary alternative to the social and economic policies of the right”.

In his new book, Free and Equal: What Would a Fair Society Look Like?, Daniel Chandler sets out such an alternative, drawn from the work of John Rawls, a giant of twentieth century political philosophy. Rawls’ work aimed to describe what a “realistic utopia” — a just, but practically achievable, society — would be. Perhaps because he avoided radical rhetoric and rarely commented on current events, many readers missed how far-reaching his proposals were. Chandler’s book should change this.

After introducing Rawls’ theory of justice, Chandler brings it down to earth in a series of proposals for reform addressing an array of topics, from free speech to taxes to organized labour. Spelling out the details in this way makes explicit how different a Rawlsian society would look from our own.

Rawls set out two principles of justice. The first is about basic rights and the political process. It says that everybody is entitled to “a fully adequate scheme of equal basic rights and liberties,” and that “the equal political liberties […] are to be guaranteed their fair value.” In other words, basic rights, like freedom of expression and association, are guaranteed to everyone in a just society; one basic right can only be restricted to protect another. Moreover, everyone should have the same opportunity to influence democratic decision-making.

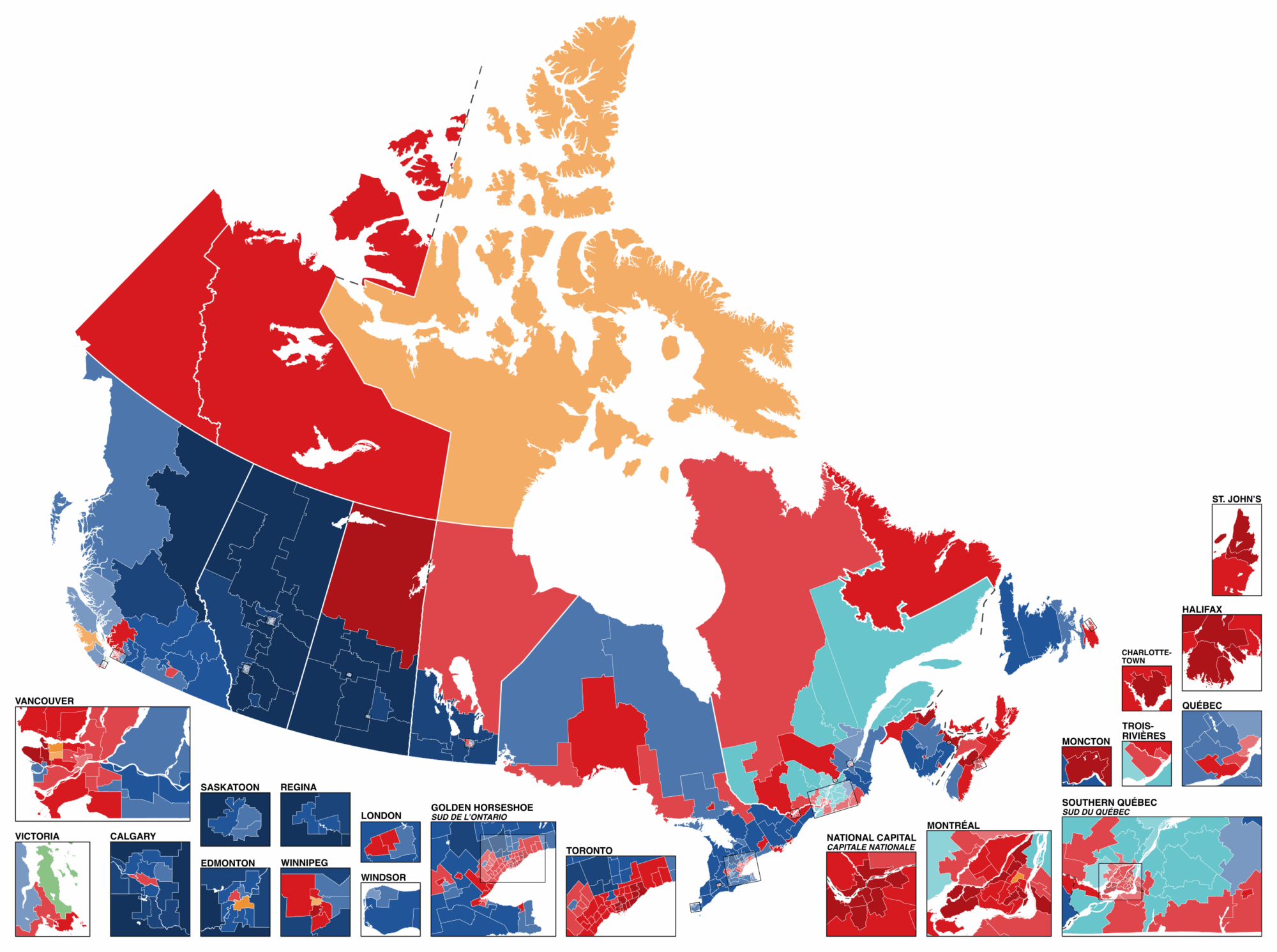

The latter idea of equal opportunity for democratic influence, which Chandler calls “political equality,” requires not only an equal right to vote, but also an equal chance to try to persuade others of your views. Democracies like Canada are far from politically equal. For example, even though we impose limits on cash donations to political parties, many people cannot afford to donate near the maximum amount. As a result, parties with wealthier supporters still have an advantage, and the wealthy have more influence. On top of this, concentration in Canadian media ownership gives some people a much louder voice than others. This became very clear in the 2011 and 2015 general elections, when newspapers across Canada were ordered by their owners to endorse Conservative Prime Minister Stephen Harper.

What can we do to achieve political equality? Chandler proposes a number of novel reforms to more evenly distribute political power. Alongside even tighter limits on donations to political parties, he suggests a system of “democracy vouchers”: an annual sum which “each citizen could contribute to the party or candidate of their choice.” This, he argues, would allow everyone to donate to political parties regardless of their wealth, and would give parties an incentive to appeal to more voters. Unlike the charitable tax credits that we already have in Canada, democracy vouchers would facilitate donations up front, and without the incentive being tied to how much you owe in taxes. Chandler also suggests a system of “media vouchers” which people could spend on their choice of media outlet, although, with the present Canadian media landscape, it would be hard to decide which outlets are eligible.

Rawls’ second principle is about what it takes for social and economic inequalities to be made fair: “first, they are to be attached to positions and offices open to all under conditions of fair equality of opportunity; and second, they are to be the greatest benefit of the least advantaged members of society.” Chandler illustrates these two conditions with the image of a competitive race. The first condition requires that everyone have the chance to take part in the race, with a fair start. The second condition — what Rawls calls the “difference principle” — is about “making sure that the prizes are fair.”

Achieving fair equality of opportunity would already require significant reforms, such as abolishing private schools to equalize opportunities for education and socialization. But it is the difference principle which has the most radical implications. As Chandler explains, the idea is that “what ultimately matters is not the size of the economic pie overall,” or giving everyone the same size slice, “but the absolute size of the slice that goes to the worst off.” Strict equality might make everyone worse off, for example, by undermining economic growth. Given this fact, inequalities can sometimes be justified, but only on condition that they tend to make the least advantaged in society as well off as possible.

This is a demanding standard. Welfare capitalism alone does not meet it, as there are many inequalities in a welfare capitalist society that are not to the greatest benefit of the least advantaged. To get us there, Chandler suggests that we introduce a universal basic income, which would ensure that everyone can meet their basic needs without the stigma and intrusive questions often associated with welfare; a jobs guarantee, with the state as an employer of last resort; and a citizens’ wealth fund, where the state buys shares in companies and distributes dividends to citizens. All this would be funded by an increase in taxes to around 45-50% of GDP (Canada’s current ratio of taxes to GDP is around 33%).

The difference principle also applies to inequalities of power, like the power of bosses over workers. Chandler argues that we should strengthen democracy in the workplace by allowing trade unions to bargain at the level of the sector rather than with individual companies and by giving workers equal representation on nearly all company boards.

Chandler’s book deserves to be widely read: his realistic utopia might be the “coherent alternative” which has been missing from contemporary social democratic politics. However, he also inherits some of Rawls’ limitations. First, Rawls assumed that society was a “cooperative venture for mutual advantage”. This assumption was criticized by the philosopher Charles Mills, who pointed out that Indigenous peoples dispossessed of their land and enslaved Black people were not included in such a venture. In Canada, the way we distribute resources cannot just look forward: it also must look back at the history of colonialism and its present-day ongoing wrongs. How do our forward-looking and backward-looking obligations fit together? As Chandler recognizes, this is not the kind of thing Rawls’ framework is designed to address.

Second, Rawls was writing for people who basically agreed on liberal democracy. What about those who do not? In a 1997 talk, Burton Dreben, a follower of Rawls, addressed this question: “One of the virtues of Rawls is that he does not waste time arguing about autocracy… To be perfectly blunt, sometimes I am asked, when I go around speaking for Rawls, What do you say to an Adolf Hitler? The answer is [nothing]. You shoot him.” Today, as right-wing authoritarians win elections around the world, the left needs a better answer. In Doctorow’s novel, fascists take up arms in a backlash against the Green New Deal. The fact that this feels easier to imagine than implementing the Deal in the first place suggests that arguing about autocracy might not be such a waste of time.

Daniel Chandler is an economist and philosopher based at the London School of Economics. He has degrees in economics, philosophy and history from Cambridge and the LSE, and was awarded a Henry Fellowship at Harvard where he studied under Amartya Sen.

Free and Equal: What Would a Fair Society Look Like? by Daniel Chandler is now available from Penguin Books.