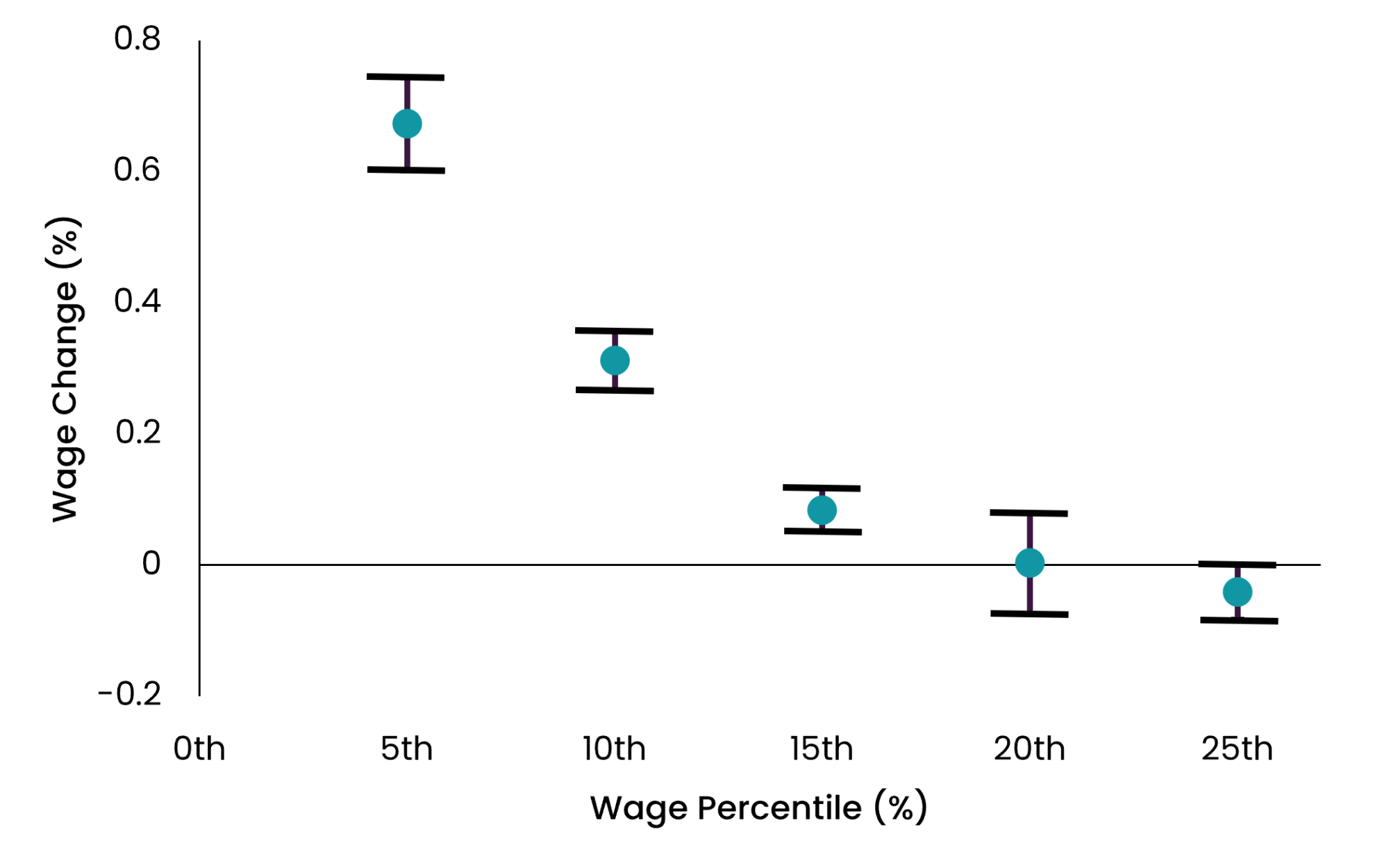

In recent decades, labour economists have established that increases in the minimum wage exert spillover effects on above-minimum wages. (Fortin, et al., 2021) This means that increasing the minimum wage not only increases wages that were below the new minimum, but also increases higher wages, found further along the distribution. To illustrate this effect, considering Canadian data from 1997 to 2013, Fortin and Lemieux (2015) determined that changes in the minimum wage affected the wages of the bottom 15 percent of Canadian workers, despite only 5 percent of workers earning the minimum wage during that period. Accordingly, minimum wage policy appears to impact three times as many workers as typically assumed, rendering it much more powerful than considerations of minimum-wage earners alone would suggest. If these broader effects of minimum wage increases were widely communicated, they could help to popularize increases among the electorate. Indeed, an investigation of how spillover effects arise, and how they bolster the effectiveness of minimum wage policy, would be useful for campaigns seeking to empower workers as they rally support for bolder minimum wage hikes.

Evidence suggests that minimum wage spillovers originate from fairness and incentive considerations within firms (Brochu, et al., 2023) To understand this, we should start by examining why employers pay some workers more than the minimum wage in the first place. On the one hand, they may do so to compensate workers when jobs require more effort or involve worse conditions than others available. (Maestas, et al., 2023) Alternatively, employers may also do so when demand for skilled and experienced labour provides workers with outside options and bargaining power. (Krueger & Hall, 2008) In either case, employers use varying levels of compensation to attract and retain suitable employees across their positions, with the minimum wage acting as the floor of this incentive structure. Accordingly, when the minimum wage increases, employers must increase above-minimum wages to maintain these compensation hierarchies, generating spillovers. (Brochu, et al., 2023) These effects are not felt evenly across the income distribution, however, with empirical evidence suggesting that these increases become smaller as one moves up the hierarchy, as employers attempt to minimize the overall increase in their labour costs. (Hirsch, et al., 2015) This means that minimum wage spillovers generate a compressive effect on the wage distribution, bolstering the ability of the minimum wage to reduce inequality.

In one of the earliest investigations of the effect of minimum wage spillovers on wage inequality, Lee (1999) considered U.S. data from the 1979 to 1991. Taking spillover effects into account, he determined that the fall of real minimum wages could explain half of the 1980s’ increase in wage inequality, and almost all of the increase in wage inequality in the bottom half of the distribution. Decades later, these findings were again affirmed by Fortin, et al. (2021) in a similar study. As such, while the rise of earnings inequality under the Reagan-Bush administration is often blamed on welfare cuts, union disempowerment, and regressive tax policies, (e.g., Plotnick, 1993; Western & Rosenfeld, 2011) the decline of the real federal minimum wage may have actually been more decisive. Importantly, the administration did not need to explicitly lower the minimum wage to produce this decline; in fact, the nominal minimum wage was actually increased in both 1981 and 1990. Nonetheless, the real minimum wage experienced a passive 30 percent drop over the decade because of inflation alone. (Fortin, et al., 2021)

Chart 1 — Estimated Effect of Minimum Wages on Selected Wage Percentiles

Shifting to the Canadian context, Fortin and Lemieux (2015) present one of the most rigorous considerations of minimum wage spillovers and wage inequality, and their results are just as striking as those from the U.S. Considering the period from 2005 to 2010, they determined that wage inequality decreased in Canada and that all of this decrease was due to increases in real provincial minimum wages. In contrast, from 2000 to 2005, real minimum wages were largely stagnant, and wage inequality increased across Canada. Clearly, in both Canada and the U.S., there are strong indications that spillover effects turn minimum wage policy into a powerful tool to counter inequality. Furthermore, these effects demonstrate how progressive minimum wage policies could rally popular support from more than just minimum-wage earners.

According to a recent study from Quebec, the strongest predictor of support for increasing the minimum wage is whether the increase will directly benefit an individual or a member of their family. (Mishagina & Montmarquette, 2021). This sense of economic self-interest is an even stronger predictor than one’s political affiliation, level of empathy, or attitude toward redistribution. As such, while we often focus on the moral virtue of a liveable minimum wage, the deservingness of minimum-wage earners, or the threat of rising income inequality, a more influential approach to boost popular support for minimum wage increases would be to demonstrate to individuals that they stand to personally benefit. Critically, as spillover effects triple the number of workers who receive a pay raise from these increases (Fortin and Lemieux, 2015) educating voters about spillovers may be the most effective method of doing so. In fact, Mishagina and Montmarquette (2021) found evidence that individuals’ opinions about minimum wages are responsive to this type of informational campaign. However, increasing the number of expectant beneficiaries is not the only way that spillovers might boost support for minimum wage hikes.

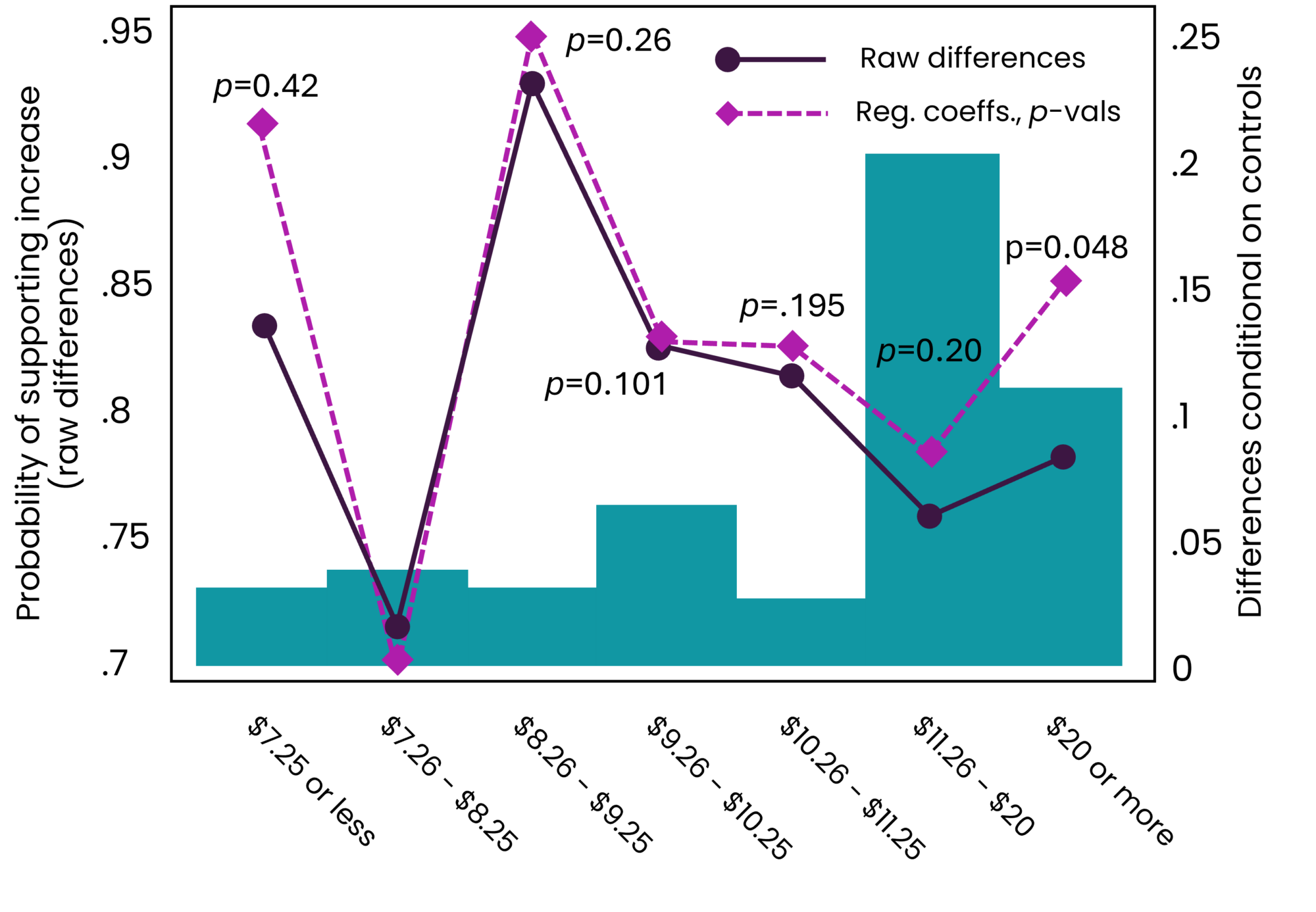

In another opinion survey, Kuziemko, et al., (2014) examined opposition to minimum wage increases across income groups. The results suggest that the strongest opposition to minimum wage increases is found among low-wage workers, specifically those who earn just above the minimum wage. This strong opposition is explained in terms of downward social comparison. Essentially, although workers who earn just above the minimum wage are close to the bottom of the income hierarchy, they can at least feel better relative to minimum-wage earners. As such, if the minimum wage were increased, their slight income advantage would disappear, and with it, their sense of superiority. However, if these workers were made aware of spillover effects and the fact that their income advantage would be preserved after minimum wage increases, one of the strongest sources of popular opposition would be neutralized. Clearly, it would seem that educating workers about spillover effects could improve support for progressive minimum wage policy.

Chart 2 — Support for Increasing the Minimum Wage from $7.25, by Wage Rate

While this article has focused on the positive consequences of minimum wage spillovers for both workers and progressive policymakers, the newly-understood importance of minimum wages cuts both ways. While spillovers make bold minimum wage hikes more powerful, they also means that decreases in real minimum wages can have stark consequences for inequality. Lee’s (1999) finding that effective decreases in the minimum wage caused half of the U.S.’s increase in wage inequality in the 1980s, and the fact that these decreases were due entirely to inflation is indicative of the strong potential for improving livelihoods by increasing minimum wages. Indeed, because of inflation, if nominal minimum wages are not regularly increased, real minimum wages are decreased. For instance, consider Alberta, where the minimum wage has not been adjusted since 2018, and as a result, the real minimum wage has effectively decreased by 17 percent over the past six years. Not only have minimum wage earners lost about one-fifth of their earnings, but a much larger group of workers have also likely experienced real pay cuts. Given the current era of high inflation, this issue has likely only worsened. The takeaway is clear: If workers are not informed about the importance of strong minimum wages and cannot enact bold minimum wage increases, inflation will have stark consequences, not only for minimum-wage earners but for the rest of the working-class across their end of the income distribution.

References

Click to expand for a full list of references cited in this article.

Brochu P, Green D A, Lemieux T & Townsend, J (2023) “The minimum wage, turnover, and the shape of the wage distribution,” IZA Discussion Paper, No. 16514. Available: http://dx.doi.org/10.2139/ssrn.4599647

Fortin N M & Lemieux T (2015) “Changes in wage inequality in Canada: An interprovincial perspective,” The Canadian Journal of Economics, 48(2), pp. 682–713. Available: https://doi.org/10.1111/caje.12140

Fortin N M, Lemieux T & Lloyd, N (2021) “Labor market institutions and the distribution of wages: The role of spillover effects,” Journal of Labor Economics, 39(S2), pp. S369–S412. Available: https://doi.org/10.1086/712923

Hirsch B T, Kaufman B E & Zelenska T (2015) “Minimum wage channels of adjustment,” Industrial Relations, 54(2), pp. 199–239. Available: https://doi.org/10.1111/irel.12091

Krueger A B & Hall R E (2008) “Wage formation between newly hired workers and employers: Survey evidence,” NBER Working Paper Series, 14329. Available: https://doi.org/10.3386/w14329

Kuziemko I, Buell R W, Reich T & Norton M I (2014) “’Last-place aversion’: Evidence and redistributive implications,” The Quarterly Journal of Economics, 129(1), pp. 105–149. Available: https://doi.org/10.1093/qje/qjt035

Lee D S (1999) “Wage inequality in the United States during the 1980s: Rising dispersion or falling minimum wage?” The Quarterly Journal of Economics, 114(3), pp. 977–1023. Available: https://doi.org/10.1162/003355399556197

Maestas N, Mullen K J, Powell D, von Wachter T & Wenger J B (2023) “The value of working conditions in the United States and implications for the structure of wages,” The American Economic Review, 113(7), pp. 2007–2047. Available: https://doi.org/10.1257/aer.20190846

Mishagina N & Montmarquette C (2021) “The role of beliefs in supporting economic policies: the case of the minimum wage,” Journal of Economic Behavior & Organization, 188, pp. 1059–1087. Available: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jebo.2021.06.028

Plotnick R D (1993) “Changes in poverty, income inequality, and the standard of living in the United States during the Reagan years,” International Journal of Health Services, 23(2), pp. 347–358. Available: https://doi.org/10.2190/H95U-EX9E-QPM2-XA94

Western B & Rosenfeld J (2011). “Unions, norms, and the rise in U.S. wage inequality,” American Sociological Review, 76(4), pp. 513–537. Available: https://doi.org/10.1177/0003122411414817