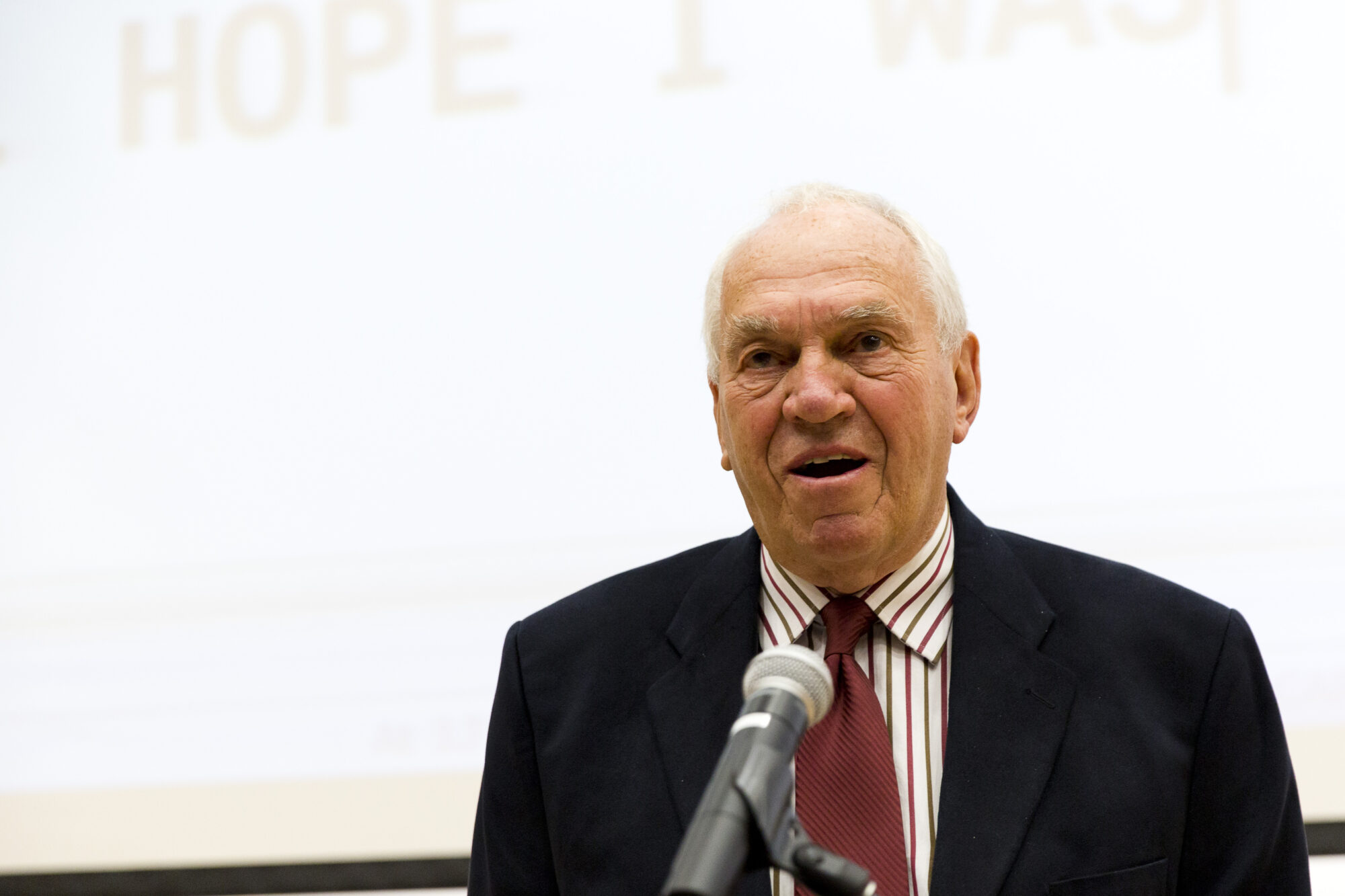

The following are remarks delivered by Luke Savage, socialist writer and researcher for the Ed Broadbent Legacy Archive project, upon receipt of the 2024 Rik Davidson Book Prize for his co-authorship of ‘Seeking Social Democracy: Several Decades in the Fight for Equality,’ by the journal Studies in Political Economy at Carleton University on November 15, 2024.

Speaking on “Which Future for Social Democracy,” Savage reflects on the intellectual legacy of Ed Broadbent and what his views offer on the state of the world today.

Good afternoon everyone. Let me first say that it’s a pleasure to be here. I want to thank Marc-André Gagnon and everyone else who has so generously organized today’s proceedings. My colleagues and I are absolutely honoured that Seeking Social Democracy has been awarded this year’s Rik Davidson Book Prize and, if our late comrade Ed Broadbent were here, I know he would be too. Thanks as well to my fellow panelists for the lively discussion so far.

In preparing my remarks for today, I was initially tempted to speak directly to the recent US election I’m sure many of us have on our minds. But I instead want to talk a bit more generally and holistically about the current political crisis as I see it, and about how I think a precarious and unsettling moment like our own should be interpreted. And in interpreting it I think we ultimately need to look beyond the confines of any single election or the events that surround it.

Then, I’m going to do my best to find some more hopeful and optimistic things to say — some of which are inspired by my work with Ed Broadbent. Here, I will certainly be channeling many of the ideas swirling around thanks to my current research project, which has been to go through Ed’s rather voluminous papers with the aim of compiling material for an archive and (before that, I hope) a book of his collected writings.

From the 1950s until just a few weeks before he passed away, Ed wrote and intervened, with astonishing range, on various political events. He also wrote more abstractly on the role of theory in politics, on the relationship of theory to socialist practice, on democracy, on neoliberalism, and on much more. Some of this material has never been published, and even what has been published has often appeared only once in a small journal or daily broadsheet.

It’s very much my hope that, after it’s all been assembled into a single, curated volume, Ed Broadbent will be duly recognized not only as the popular and effective political leader he is widely known to have been, but also as the invaluable political intellectual I believe was. Stay tuned.

The Dead Center

To begin my remarks in earnest: roughly two years ago I published a book called The Dead Center whose main thesis, to generalize, was that the liberal order is suffering a deep and profound crisis that goes well beyond the result of any particular electoral event or economic downturn. Even though liberalism remains politically and culturally hegemonic there are fundamental ways in which liberal democracy is simply not working even on its own terms. (And, in my view, neither the nature or the extent of this crisis are well understood by liberalism’s leading politicians and intellectuals.) Many of the troubling developments we see in the world today, including the ongoing resurgence of the radical right, originate in my view from within the liberal democratic order itself.

The Dead Center came out in the fall of 2022 and I think it would be fair to say the argument was somewhat unfashionable at the time. Among other things: Joe Biden had just defeated Donald Trump in the 2020 US presidential election; governments around the world of various ideological persuasions were turning on the spigot and spending on various social supports and pandemic measures in a manner that seemed to depart from the ethic of fiscal restraint that’s largely been the norm since the 1980s; the Biden administration was invoking Franklin Delano Roosevelt, and activist government (so we were told) was back. In response to these developments, some commentators even ventured the idea that neoliberalism itself was dead.

As you can probably imagine based on my remarks thus far, I demurred from that rather optimistic appraisal of things. And, needless to say, the two years since have offered little to change my mind. I believed then and believe even more strongly today that our crisis is rooted in the increasingly post-democratic character of many liberal institutions and indeed the hostility of a not insignificant number of liberal politicians and commentators to popular democracy itself.

After Trump’s first victory and in the wake of developments like the Brexit vote there was a whole raft of discourse that sought to blame democracy for everything that was ailing the liberal order. I went back and found a few fun examples to give you the flavour: “Democracies end when they are too democratic” (Andrew Sullivan, New York Magazine); “Britain’s democratic failure” (Kenneth Rogoff, The Boston Globe); and my personal favorite, by way of James Traub in Foreign Policy: “It’s Time for the Elites to Rise up Against the Ignorant Masses.”

Democratic Deficit

Now, my premise is something like the exact opposite of that. I think liberal democracies suffer from a profound democratic deficit, and I’d like to outline briefly what it is I mean by that.

There’s a lot that might be said here, but here are two fundamental points:

First, the traditional structures of democratic participation have broken down. Political parties with mass memberships, an autonomous civil society, regular elections under universal franchise, etc.; all of these persist in varying degrees but in many important ways, no longer exert real influence on the major institutions of state, economy, or society. As a result, the steering mechanisms of liberal democracy are increasingly severed from popular input or control.

Public opinion, it seems to me, now often tends to have more of an influence on the narratives politicians invoke to legitimize major political decisions than it does on the nature or substance of those decisions. Let me briefly offer a few recent illustrations.

We might look, for example, at the way states opted to respond to inflation: unelected heads of central banks, who are architects of state policy but are often subject to little actual democratic oversight, raised interest rates, drove up unemployment and eroded the incomes of the majority. That’s a pretty clear cut example of elite policymaking not done in the interests of the average person, and there’s not much anyone can do about it. We can’t vote the central bankers out because we never voted them in in the first place.

Another, somewhat different example I’d offer is the George Floyd protests in 2020. These were by some metrics (in the US at least) the largest mass protests in history, and they failed to yield a single major policy change. The liberal class instead metabolized them primarily at the level of image and symbol. So, Democratic politicians donned their Kente-cloths and took a knee, but there was no fundamental change in public policy even though the Democratic Party won trifecta control of the US government.

Just as a general matter, there’s a host of polling you can look at across a range of issue areas where public opinion has little to no impact on the political mainstream. I do a lot of work on the United States so I hope you’ll forgive a further American example, but just look at how overwhelming public support for universal healthcare has consistently been, across party lines, in the United States.

Last I checked: Medicare for All was supported by 69 percent of registered voters including 87 percent of Democrats, the majority of Independents, and nearly half of Republicans. In spite of that, even many supposedly progressive politicians quite literally run away from socialized medicine; as sure a signal as any that they are much more responsive to other constituencies than they are to popular opinion.

This brings me to the second fundamental point about our current crisis and the democratic deficit: that is that the advance of neoliberal capitalism has completely eroded many of the barriers that once separated both the political realm and the social realm from market activity and market logic.

In politics, this has meant the ongoing capture of many liberal democratic states by major financial institutions and large corporate firms. It’s meant the wholesale reimagining and reconfiguring of democratic governance such that the state is conceived more like a giant corporate firm whose main function is to facilitate market activity rather than pursue any kind of public good external to or independent from the market.

In the social realm, the creep of neoliberalism has meant that virtually everything has become either an active or a potential site for profit, commodification, and rent seeking — something that now extends beyond the physical world and into digital and virtual space as well.

Social Democracy’s Tradition and Future

Now, given all of this I think it’s really little wonder that liberal democracy is now facing a serious crisis of legitimacy: representative government is increasingly unrepresentative; both political and economic institutions are often working against the grain of popular opinion and the material needs of the popular majority, in some cases quite actively trying to discipline them; the narrow interests of powerful market actors and the preeminence of private profit seeking have corrupted and eroded the social contract while transferring wealth and power upward and gutting public goods, and people everywhere are facing rising economic precarity and insecurity as a result.

Our remit for this panel was Which Future for Social Democracy? And I am firmly of the view that at least part of the answer to that question can be drawn from the past. So in that spirit, I’d like to use my final minutes to say a few more hopeful things inspired by my work with Ed Broadbent and immersion in his ideas.

In a moment like our own, we’re liable to hear calls to retrench in our expectations; to be less ambitious in our political or policy goals; to be narrower and more minimalist in our demands. I think this would be a mistake, not only because the crises we face — from inequality and economic precarity to climate change — necessarily demand the kind of bold and radical solutions pursued by the left throughout much of the twentieth century, but because the best of the social democratic and democratic socialist traditions offer us a rich conception of democracy from which to draw inspiration in a time of democratic decay.

If a single idea animated Ed Broadbent’s seven decade fight for equality, it was that the rights and freedoms afforded by the liberal state (though important) are, on their own, an inadequate foundation for real democracy and human flourishing. Those things require, as Ed saw it, a much more expansive vision of rights: the right to broad, guaranteed social protections, the right to housing, the right to secure employment, the right to healthcare and education. They require the deepening of democracy within political institutions and its extension to economic institutions and economic life as well.

In my view, this rich vision of democratic equality can and should continue to be our compass in this era of uncertainty and crisis. As we look ahead to a future bound to be ridden with disruptions — economic, ecological, technological — a political project able to deliver stability and security but also able to protect and expand the democratic agency of citizens will have great appeal. In the years ahead we must turn our attention not only to repairing and reimagining a social contract stripped to the bone by the forces of neoliberal globalization, but also to rebuilding the foundations of our democratic structures so that they reflect the needs and interests of a broad majority.

A barren technocratic liberalism may be ill-equipped to carry this out. But I believe that democratic socialism can. And, in that spirit, I’d like to give the final word to our late comrade Ed Broadbent, who said in his very first speech to Parliament in 1968:

We have a duty … not simply to praise our past and celebrate our present, but also to create the future. No amount of parliamentary reform, social razmataz, or fiscal responsibility can lead to a just society. At the very most they can remove little pockets of inefficiency [and] the basic unjust and unequal structure will remain. What we require is leadership dedicated to the democratisation of society as a whole.

Thank You.