It is now often said, with reason, that the environment and the economy are not in conflict. But it is even more true to say that seriously addressing the crisis of global climate change could revive a moribund global economy.

The World Economic Outlook (WEO) released by the International Monetary Fund (IMF) in April of 2016 once again forecast very slow growth, and argued that economic stagnation is likely to be self-sustaining. This is due to very low levels of business investment, combined with high levels of household and public debt which constrain household and government spending.

Ultra easy monetary policy is unlikely to revive effective global demand and to lower high rates of unemployment and underemployment.

Meanwhile, there is growing pessimism among many economists that information technology let alone the so-called sharing economy will significantly revive business investment. Robert Gordon argues quite persuasively in his new book, The Rise and Fall of American Growth, that computers, robotics and other advanced technologies have, to date, only had modest impacts upon productivity, job creation and rising living standards compared to major innovations of the past such as widespread electrification and the birth of the mass production assembly line.

But the world does, as the IMF underlines in a special feature in the WEO on the energy transition, have a massive challenge to deal with in terms of the needed reduction of greenhouse gas emissions.

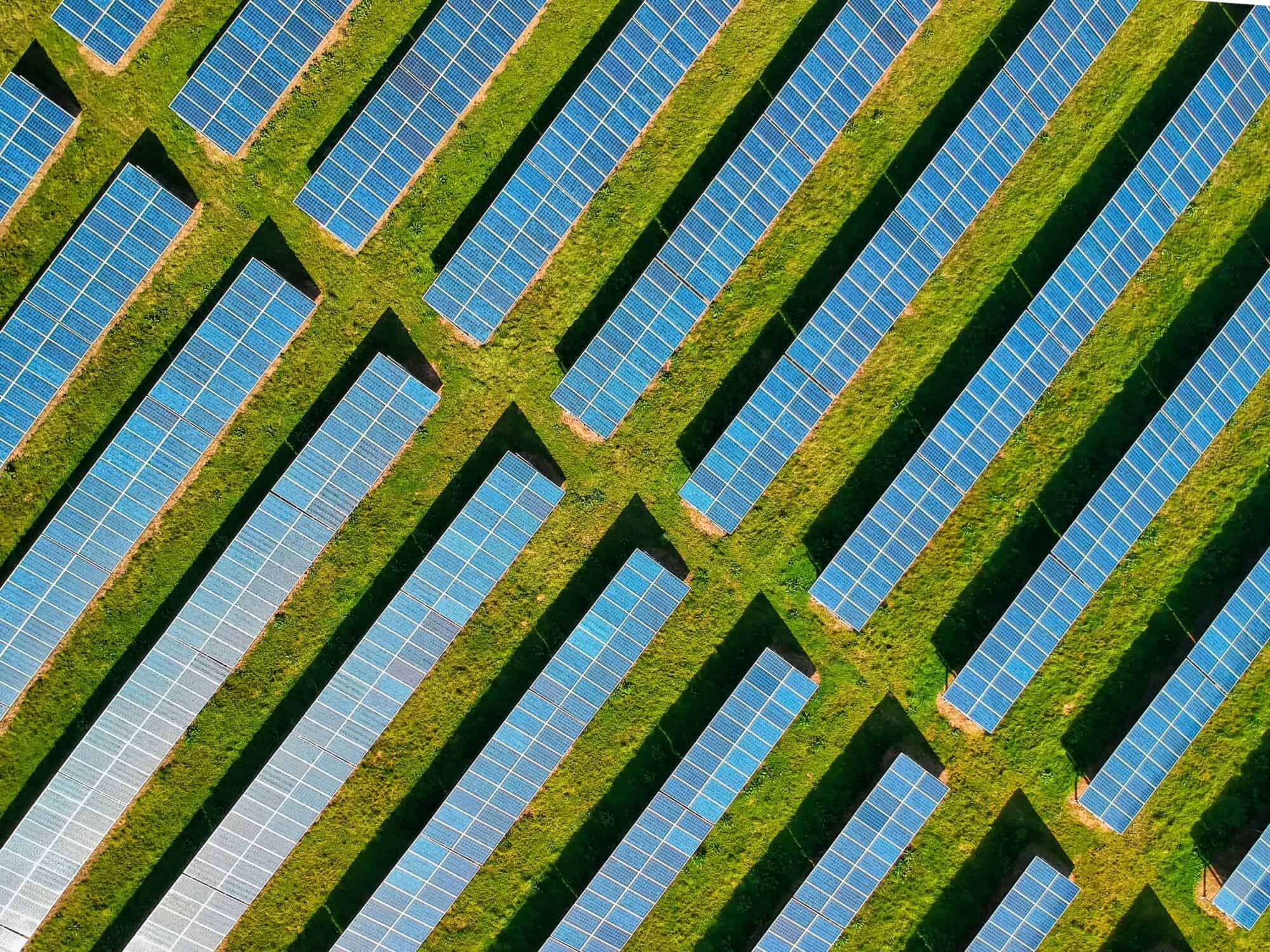

85% of global primary energy consumption still comes from carbon-based fuels—coal (30%), oil (30%) and natural gas (25%) with only 15% coming from nuclear and hydro power plus renewable forms of energy such as wind and solar power. The latter are growing rapidly, but from very low levels.

Many developing countries, notably China and India, are still expanding their use of coal, the dirtiest fuel of all in terms of carbon content. Indeed the share of coal in global energy consumption has been rising for the past fifteen years, despite falling use in the advanced economies.

The IMF reckons that it will be very challenging to lower greenhouse gas emissions at a time when the price of oil, natural gas and coal are all at very low levels, As they say, “to avoid the irreversible consequences of climate change induced by greenhouse gas emissions, the energy transition must firmly take root at a time when fossil fuel prices are likely to say low for long.”

The fifth assessment report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change highlighted the risks of allowing global temperatures to rise two degrees above pre-industrial levels. Damaging impacts are already to be seen in record high global temperatures, heat waves, prolonged periods of drought and forest fires, all of which impose large economic costs.

Scientists calculate that the world has already used up about one-half of the carbon budget needed to avoid catastrophic climate change, that greenhouse gas emissions must peak very soon, and must fall by another half over the next twenty years. This will require huge reductions in coal based power generation, and dramatic changes to existing transportation system and the design of buildings and industrial processes.

The IMF argues that “(s)hort of pervasive and economically viable carbon capture and storage technologies, the planet will be exposed to potentially catastrophic climate risks unless renewables become cheap enough to guarantee substantial fossil fuel deposits are left underground for a very long time, if not forever.” Projections based upon status quo policies, however, indicate that the share of renewables will rise only slowly, especially if fossil fuel prices remain severely depressed

The IMF notes that public sector research and development in clean energy and energy efficiency and rising economies of scale have paid off in rapid reductions in the cost of renewable energy. They call for a global floor price for carbon, and a rising global carbon tax as the most efficient way to drive the energy transition in a period of low carbon prices. They also call for more aid to promote clean technology use by developing countries.

Truly massive public and private investments will have to made in research, in energy conservation and in the production of renewable energy over the next few years if we are to meet and exceed the goal recently set in Paris to stop to avoid global temperatures from rising by more than two degrees.

On net this transition would be a big positive for jobs since decentralized energy production and more energy efficient processes are also more labour intensive. For example, added labour and materials in new construction substitutes for higher energy consumption over the life of a building.

The sheer scale of the needed energy transition is such that it could drive a global economic recovery. But only if our political leaders are up to the challenge.