Political democracy is not enough. Social democracy is our goal…We must not take refuge in the rhetoric of modern conservatives who say political democracy is sufficient…On the contrary, we must face all issues of work squarely, certainly recognizing both priorities and complexities, and yet remaining firmly committed to the building of that fuller kind of democracy which alone can make it possible for the lives of Canadians to be both just and exciting.

Ed Broadbent

What concept is more celebrated in Canadian society than that of democracy? How often are Canadians called upon to appreciate the fact that they have the ability to freely choose their officials from numerous parties in a trustworthy electoral process? How often are we told that servicemen and women have died, and continue to die, for our right to vote and have a voice within our society? The idea that Canada is a democracy, and that democracy is good, are as close to two universally-accepted statements that one might make. But this only really applies to the boundaries of politics, wherein all adult citizens have a right to vote and seek public office. It does not apply to other societal arenas, the most important one being our workplaces, which are in essence little autocracies, where owners and managers exact immense power over workers, even in unionized environments, but especially in workplaces without collective agreements.

Unfortunately, this fact is too rarely addressed in today’s mainstream political discourse, in part because the left has largely discarded it as a primary platform issue. With the rise of neoliberal politics, the left across the western world began to de-emphasize the notion that the economy was best when controlled by democratic interests. Certainly, the left in Canada as represented by the NDP hasn’t wholesale given up on the importance of public ownership and organized labour, but over the last thirty years most social democratic bodies have retreated from a commitment to build an economic democracy.

In my view, economic democracy needs to be reprioritized by the contemporary NDP as a central plank of our social and economic policy. We live in a time of unimaginable wealth held in concentrated personal and corporate hands. These companies and individuals have major sway over local, regional, national, and sometimes even international governments. Recently, major cities across North America have been applying to land an Amazon shipping centre in a process that essentially amounts to grovelling before the feet of the world’s richest man and his company. Such power in the hands of one man, or one company, is the antithesis of a democratic economy and a democratic society.

Further, many people are concerned about humanity entering a new, unprecedented phase of automation, which will render millions of workers of both brain and hand unemployable. One popular remedy bandied about is a Basic Income Guarantee to keep those rendered jobless with the ability survive independent of work. But this solution leaves a great deal to be desired, chiefly because it would fail to address the fact that only a sliver of people will fully benefit from economic transformations that belong to the communities whose collective labour made everything possible. More than programs permitting people to subsist, we need democratic mechanisms to ensure that a new industrial age doesn’t lead to a further bifurcation between those with and without industrial power.

Furthermore, Canadian social democrats don’t need to reinvent the wheel when it comes to these questions, because under the Federal NDP leaderships of Tommy Douglas, David Lewis, and Ed Broadbent, the issue of building a more democratic economy was one of the major intellectual drivers of party philosophy. My view is that the Canadian social-democratic left—which has always placed great weight on its historical roots—has much to learn from these three leaders on this front in particular.

Tommy Douglas was convinced as the 1970s approached that the next big step in Canadian history was just around the corner. He saw Canada build up robust institutions of political democracy, along with a competent—if still not comprehensive—system of social security. But the missing piece was that of economic democracy, meaning that the NDP must turn its “attention to the second phase of socialist philosophy, which is to achieve the democratization of the economy.” Douglas never wed himself to one specific definition of the concept, drawing inspiration from Yugoslavia, West Germany, and Sweden, but suggested that it would include an increase in public ownership, a greater recognition of union rights, employee representation on company boards, and a conviction that because societal progress is a collective endeavour, the fruits of that endeavour must be democratically shared:

In a complex and inter-dependent society like ours workers should not be tossed on the human scrap heap as the victims of technology. Scientific and industrial progress are not due to the efforts of employers alone…All segments of our society…have contributed to advances and all should have a voice in making the decisions that affect their interests…Industrial peace in the future will be largely dependent upon our ability to build economic democracy as a corollary to our political democracy. Workers already have the right to decide who shall govern them; they should equally have a voice in determining their economic destiny. To deny this is to reduce democracy to a periodic stint at the ballot box.

David Lewis likewise highlighted the undemocratic structure of workplaces. This reality, more than even wages and benefits, triggered industrial class conflict. He felt that employers did all they could to resist worker and public power because it limited their own. In spite of this, he felt social democrats must persistently strive towards “participatory democracy: the right of the worker to have some effective voice in the decisions that affect his life.” But more than facilitating this through collective bargaining, Lewis would challenge contemporary property rights, because those rights were there primarily to protect the holders of capital, and not workers nor all those who held only token amounts of personal private property. In doing so, Lewis argued that workers should have the property right to their job just as legitimately as the ownership conferred by capital investment.

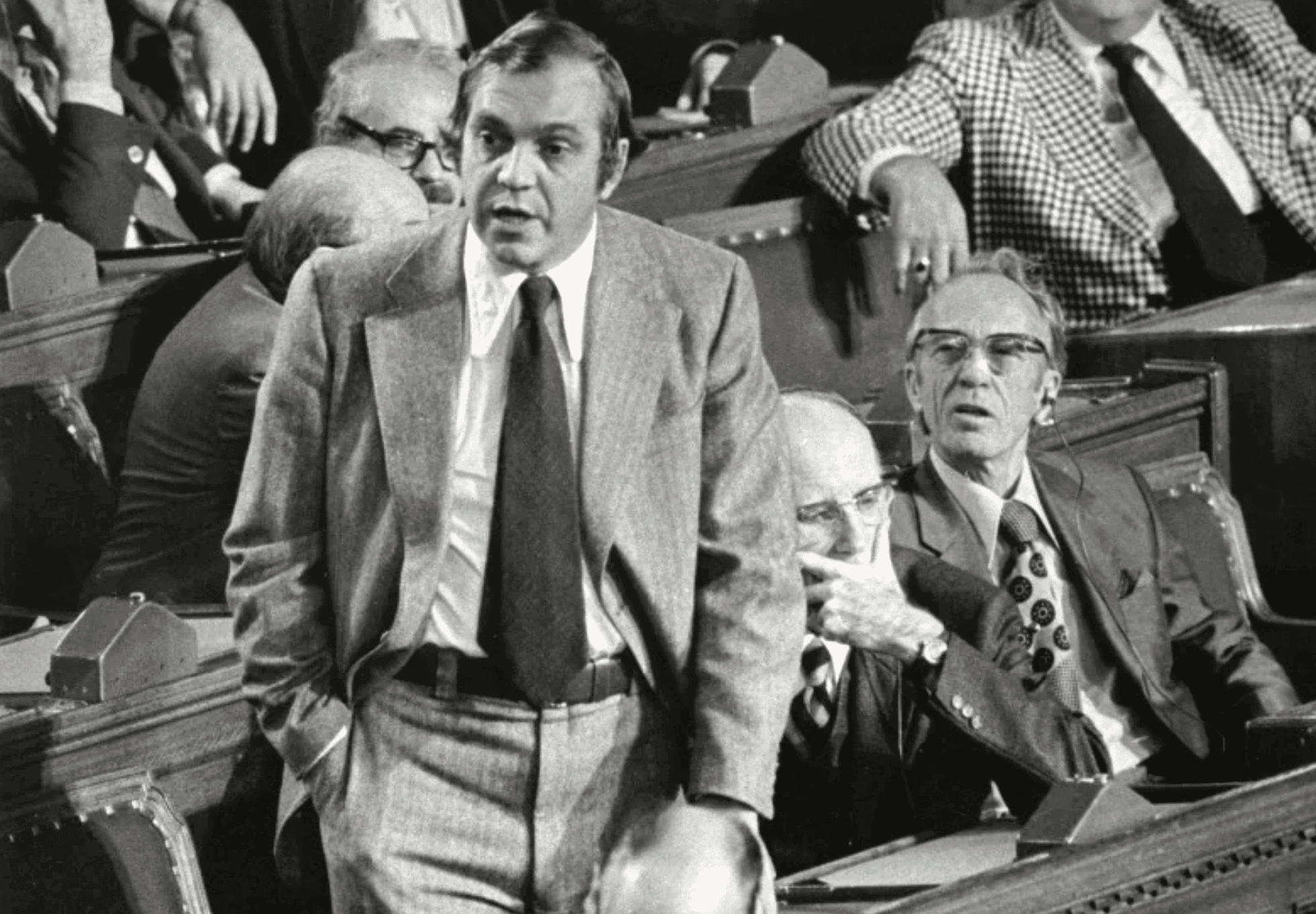

But of the three leaders, Broadbent himself was most intrigued by democratizing the economy, especially because he felt that “Canada is a parliamentary democracy, but an industrial autocracy.” Again, the issue here was that while elements of economic democracy existed in Canada through crown corporations and collective bargaining, they failed to manifest in what Broadbent called “effective power” for regular Canadians, by which he meant the ability to do more than simply resist and consult. The only solution was to exchange an economy “controlled by a private few, with one controlled by the public many.” This would be predicated on the dissolution of the “so-called prerogatives of management…that makes our present economic institutions inherently unequal and inherently undemocratic.” And while Broadbent’s words here certainly ring as radical and provocative, he was not simply speaking for dramatic impact:

This is not a Utopian ideal…Autocracy is no longer a practical form of government in industry, and will not be tolerated by the new generation of workers…They demand a more humanized, more democratic environment in the workplace and insist that enterprises operate in a manner consistent with the welfare of the community as a whole. Politicians and governments should encourage this revolutionary change.

Ultimately, what all three of these men emphasized was that however important things like Medicare, education, and social security were, they did not constitute the outer boundaries of the social-democratic project.

Put another way, what fundamentally distinguished social democracy from liberalism was a conviction of who should control the economy, with liberals saying it should be within largely private control, and social democrats claiming that, through various means, the economy should be controlled publicly.

Canadian social democrats, simply put, need to re-embrace the value in challenging private property’s dominance over the state. This isn’t to say the party is without existing ideas on this front. Andrea Horwath’s Ontario NDP is pledging to re-nationalize Hydro Ontario, and is calling for a reversal of many contracted out public services. Similarly, Niki Ashton’s federal leadership campaign made public ownership a central plank, while Charlie Angus had specific policies that would encourage worker and community-owned enterprises. Still, much more must be done on this front, and as we’ve seen, specific lessons are found within the party’s own recent history.

Jagmeet Singh’s NDP has already made impacts on issues like overhauling our tax system with a view towards a more equitable society. But if the party wants to offer a unambiguous distinction between itself and the ostensibly progressive Trudeau Liberals, a platform predicated on democratizing workplaces and the wider economy is a fantastic start, especially when aligned with provincial NDP sections willing to promote the same objectives in those jurisdictions where they have the most power.

This sort of change won’t happen overnight, even if social democrats are swept into power across much of Canada. But having a democratic economy serve as a long-term objective for the Canadian left is a worthy one that is both loyal to our political traditions, and forward-looking in addressing the defects of 21st century capitalism.