The current federal election is being fought against a backdrop of deepening inequality and the social problems that accompany it. Promises to “make things better” will no doubt be uttered throughout the campaign.

As we mark another Labour Day, it is important to remain discerning of the policies on offer.

Our recent research suggests that many public policies that have been sold to Canadians as helping them boost their pay cheques may be making things worse. On this day when we reflect on the hard won gains of workers and trade unions, let’s consider some prominent public policies that have contributed to the stagnation of real wages and, consequently, deepening inequality.

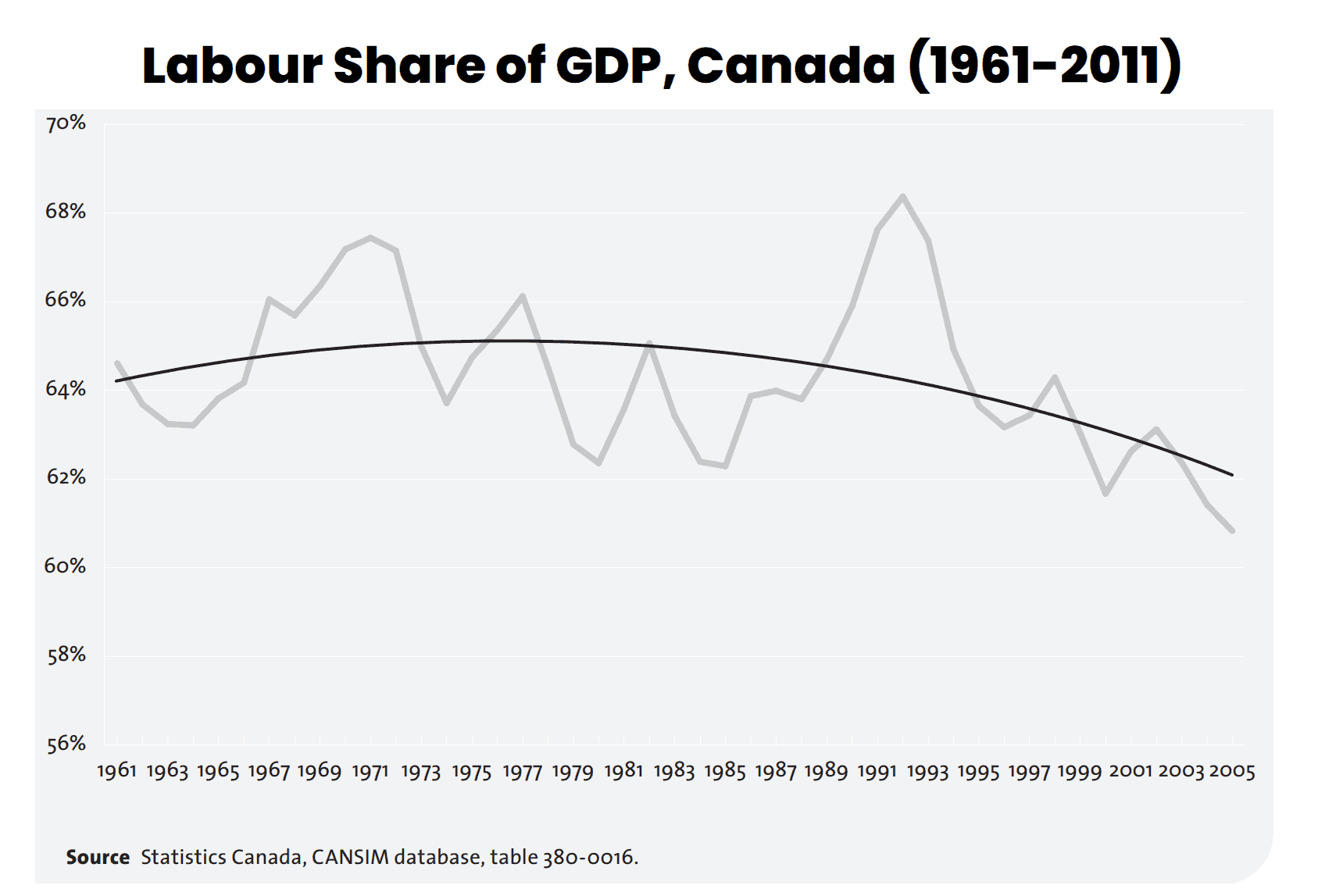

To understand the troubling trends in income inequality, looking at the way the national economic pie has been distributed is instructive. The data below shows you what has happened to pay cheques over recent decades. As labour’s share of GDP declines over time, workers have been getting a smaller slice of the national economic pie.

The trend is unmistakable: the decline in the labour share of GDP means that money that used to flow to pay cheques is now going elsewhere.

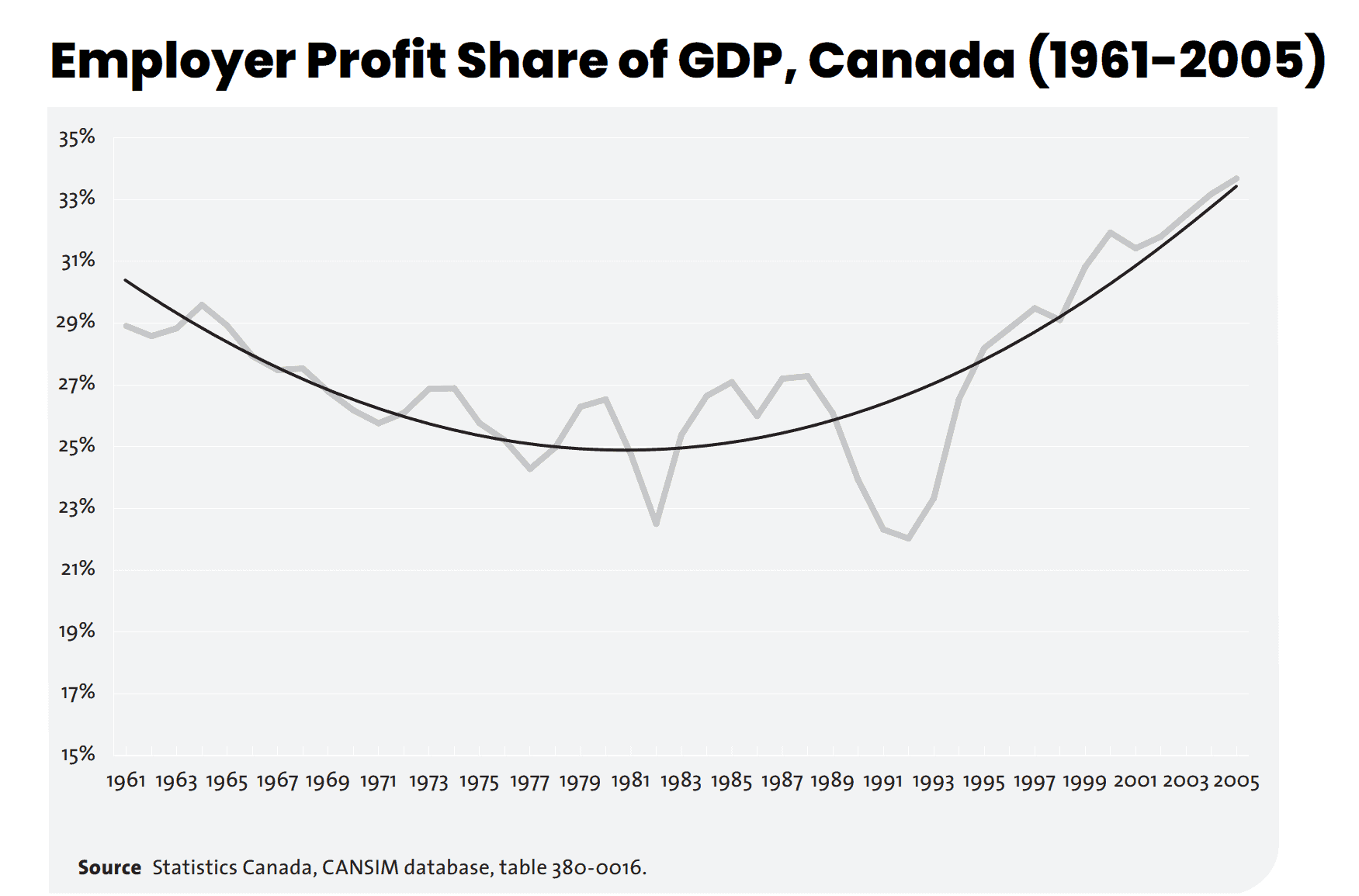

If workers are losing, then who is gaining?

The following shows that the share of profits for employers has grown. Employers are getting a bigger slice of the economic pie, while workers are taking home less.

These two graphs tell a troubling story. Unlike the relatively more equitable income distribution of the 1970s, we now have an economy that skews income away from workers and towards employers. This shift in income distribution evident in these graphs provides a snapshot of an important dimension of inequality in Canada.

What is causing this shift in income distribution in the first place?

While there are a mix of factors, a key one is the role that stagnating real wages have played in driving this fall in workers’ share of the economic pie. To really make a difference in inequality, we have to address what is causing the failure of paycheques to grow as our economy becomes more productive.

Our research suggests that some of the government policies that were sold to Canadians as those that would boost their wages may in fact have contributed to wage stagnation and growing income inequality.

For decades now, the federal government has been following policies that were supposed to boost productivity. Don Drummond, a Canadian productivity guru, has a nice run-down of these sorts of policies. This productivity agenda includes international trade and investment agreements, lower business taxes, deregulation, and the restructuring of Employment Insurance. These and many other policy initiatives were intended to maintain low and stable inflation, reduce government deficits and debt, and increase what is euphemistically referred to as “labour market flexibility.”

Canadians were told that what was good for productivity would be good for workers. But what about is boosting productivity supposed to be so good for workers?

Most economists assume that growing productivity will be translated into rising paycheques. This is often asserted as a truism: “Ask any economist and he or she will tell you that faster productivity growth leads to higher real wages…” But there is no necessity that policies that raise productivity will lead to higher real wages.

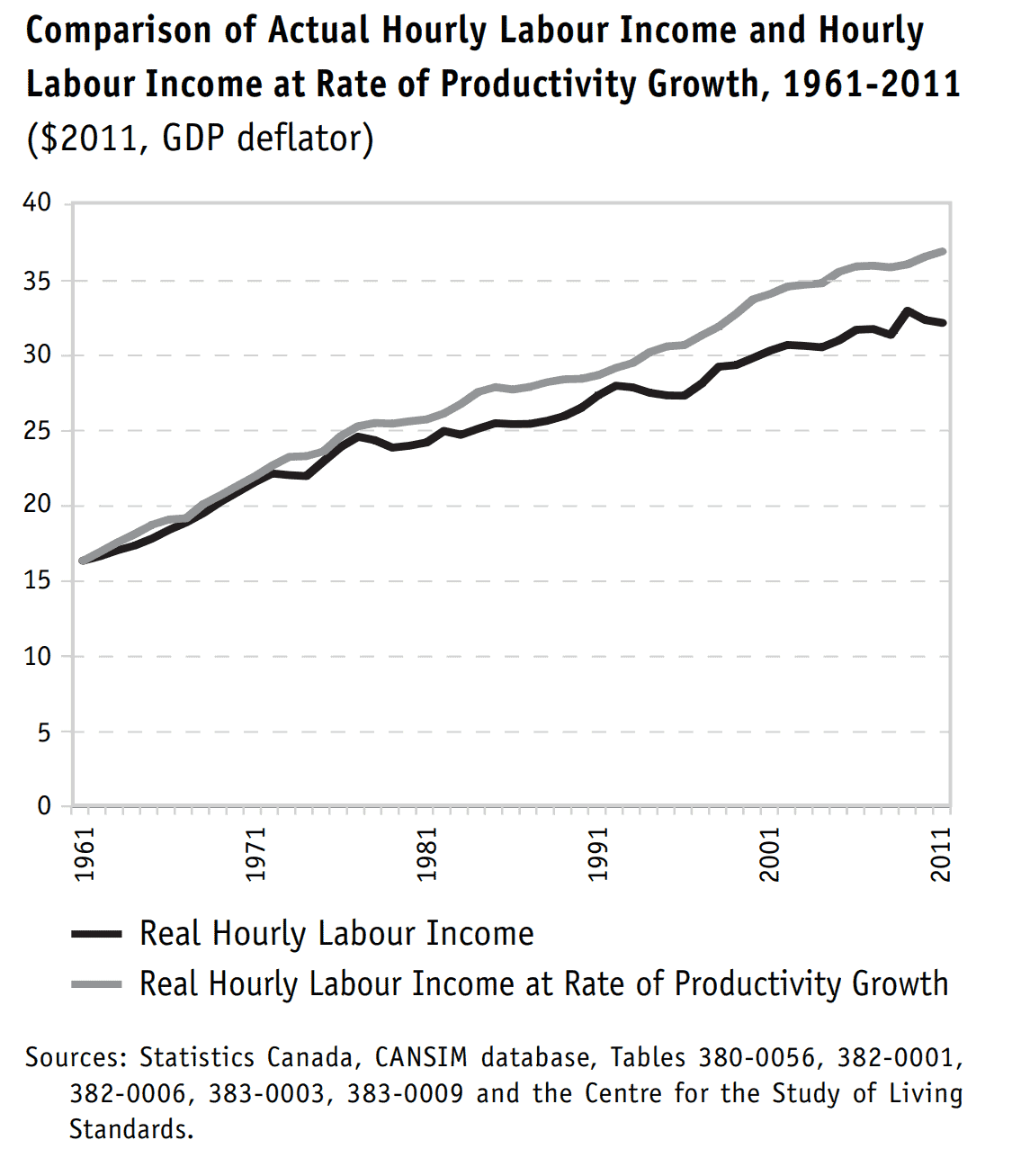

As the data below shows, while productivity has been growing in Canada since 1961, real wages have fallen behind.

The last chart is really a reflection of figures one and two: as the lines in figure three diverge, more of Canada’s income is allocated to profits for employers and away from wages. The cumulative impact of this trend means that, by 2011, average labour income per hour including benefits (expressed in 2011 dollars) was $32.20, while it would have been $36.97 had it followed average productivity growth. In other words, workers are not reaping their proportional share of productivity gains.

If pay followed productivity, workers would have earned an additional $14.81 per cent per hour; instead the $4.77 differential went to employers. An extra $4.77 per hour for every worker across the whole economy is significant amount of money.

In fact, if pay had matched productivity, full-time workers would taken home approximately $9,540 more on average in their annual paycheques.

Behind the divergence in pay and productivity growth

Why is it that Canadian workers are not getting the fruits of that growing productivity?

Our research looks at the possibility that the very policies that governments said would help our paycheques by boosting productivity have undermined workers’ ability to secure the benefits of productivity growth.

To test this hypothesis, we conducted an econometric analysis for all Canadian provinces between 1981 and 2010. We evaluated several policies that have been prominent in the “productivity” agenda outlined above. If these policies were helpful to workers’ paycheques, we would expect to see that the gains from productivity growth were being passed along as rising real wages. Instead these policies are correlated with an increased divergence between pay and productivity growth.

Why might these productivity policies be undermining workers’ paycheques? Our analysis suggests that the government policies promoted in the name of the productivity agenda could have hurt workers’ bargaining power, making it harder for workers to get a fair share of growing productivity.

Deliberate government policies can have important impacts on workers’ bargaining power. For example: cutbacks to EI make the prospect of a potential job loss more punitive. The more fearful workers are of the consequences of job loss, the more likely they are to settle for less rather than risk the possibility that they may lose the jobs they have. The North American Free Trade Agreement (NAFTA) made it easier for firms to relocate abroad (and to threaten to move if workers fought for a better wage deal), limiting worker’s ability to bargain for higher wages.

Many polices that fall under the “labour flexibility” heading that have constrained union membership, have made it more difficult for workers to bargain collectively, thereby reducing their bargaining power. Low minimum wages also made workers more vulnerable. Since the minimum wage is often taken as a reference point in wage negotiations, lowering it would decrease overall wage prospects for many lower-wage workers. And workers who are worried about potential unemployment realize that finding another job may mean a minimum wage job.

Finally, high unemployment rates of recent decades indirectly point to public policy. Government obsessions with keeping inflation low resulted in the relatively high unemployment rates of the 1980s and 1990s. And when unemployment is high, worker bargaining power is reduced.

So what’s the upshot of all this?

While politicians told Canadians that pro-productivity policies would be good for our paycheques, there is reason to believe just the opposite. These policies not only failed to produce the stellar productivity rates that their advocates hoped, they also may have inhibited worker’s ability to gain from productivity growth.

As Canadian paycheques failed to keep up, the distribution of income in Canada swung to the disadvantage of workers.

So this election season, any party that really cares about inequality has got to look at pay cheques. While governments can do lots of things to lessen inequality, it is an uphill battle to try to fix if wages are falling behind.

On this Labour Day, let’s take seriously that policies that help workers get a better deal will set the stage for a meaningful reduction in inequality in Canada.