While the Federal New Democratic Party could never rely on a majority of union members’ votes, that support now appears as elusive as ever. Indeed, formal ties between the NDP and the labour movement are considerably weaker than they were at the time of the party’s birth in 1961. The crisis of social democratic electoralism, the impact of campaign finance reform, and ongoing concerns about the party’s electoral viability have all contributed to a weakening of the union-party link.

However, the loosening of ties between labour and the NDP has not shifted the landscape of labour politics in the direction of a more left-wing brand of working-class politics as some on the labour left had hoped. Rather, the opposite has occurred, as evidenced by the clear emergence of fair-weather and transactional alliances with Liberals and Conservatives as the main alternative to traditional partisan NDP links in the realm of electoral politics.

History and Institutional Links

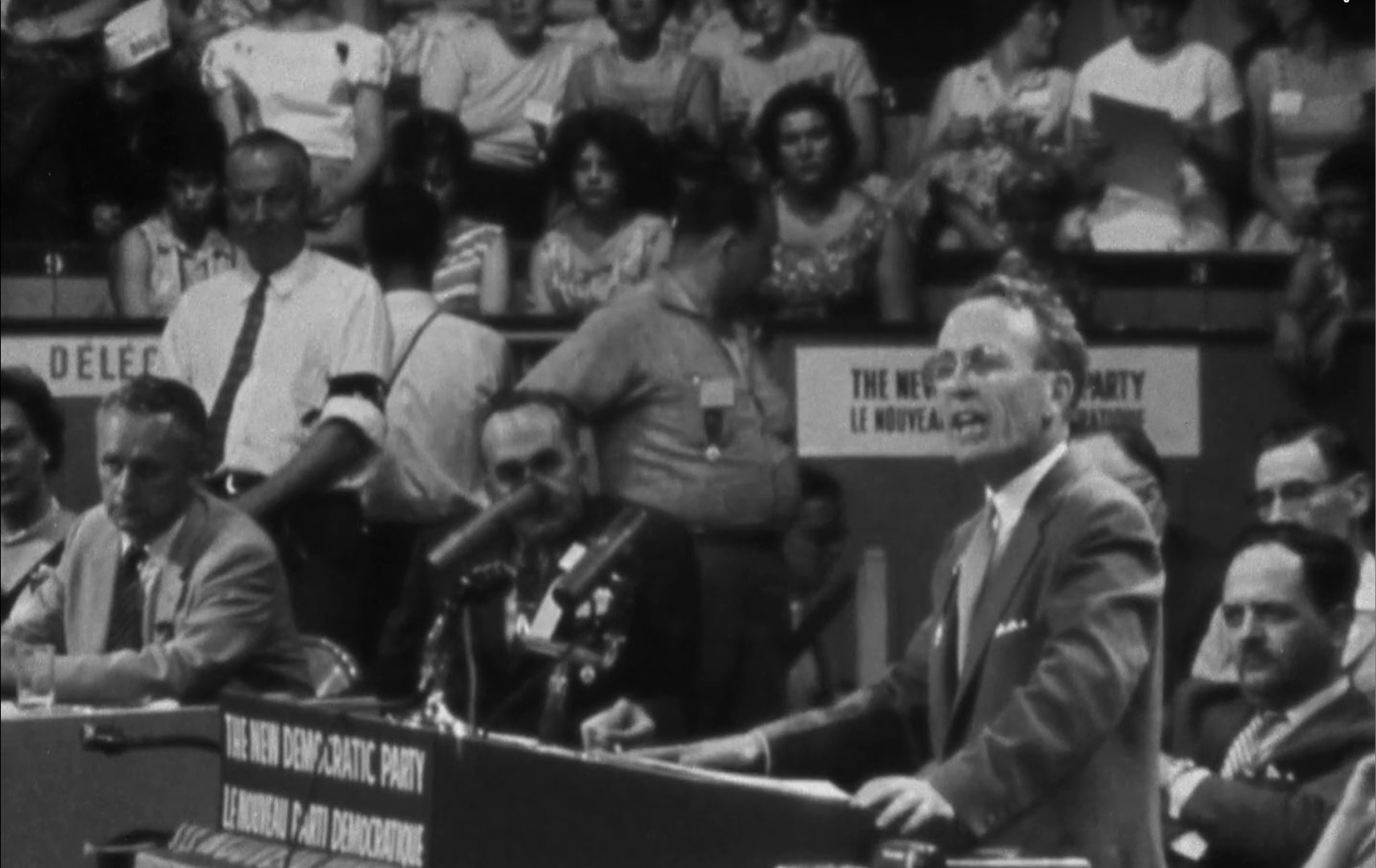

When the NDP was founded in 1961, it was heralded as the political voice of Canada’s labour movement. Born from a partnership between the Canadian Labour Congress (CLC) and the Co-operative Commonwealth Federation (CCF), the party’s architects envisioned the NDP would realign Canadian politics along a left-right axis and unite workers under a single political banner. Yet, despite the initial fanfare, the relationship between the NDP and unions was never as strong as many assumed—and in recent years, it has only grown weaker.

There was never really a “golden age” of NDP-union relations. Despite widespread support from industrial union leaders and provincial federations of labour to launch the party, the relationship has always been organizationally weak, in relative terms, never coming close to matching the strength of labour-social democratic party ties in Britain, Australia, and across Western Europe. In fact, at its peak, union member affiliation to the NDP reached just 14.6% in 1963, only a couple years after the party’s launch in 1961. By 1984, that number was cut in half and has declined even further since.

NDP-union relations were further weakened in the context of the party’s ideological shift away from its social democratic roots beginning, in earnest, in the 1990s.

Nevertheless, there is no question the NDP survived its first two decades as a result of its close partnership with the labour movement. The structural and financial ties between labour and the party, while not as strong or reliable as they could have been, kept the NDP afloat. As detailed by Harold Jansen and Lisa Young, unions contributed an average of $1.9 million annually to the NDP between 1975 and 2002, representing 18.4% of the party’s revenues. In election years, that average increased to $3.7 million, or 28.1% of overall party revenue.1 Labour also played a critical role in providing research, campaign staff, candidates, and organizers to the party at election time. Moreover, unions traditionally co-signed loans for the party to run its election campaigns. When the federal government announced a curtailment of corporate and union donations in 2003, unions moved swiftly to help the party purchase a building in downtown Ottawa to be used as a permanent headquarters and as collateral with which to secure future campaign loans.

Campaign finance reforms prompted the Federal NDP to modify its constitution to do away with per capita payments by union affiliates and instead required them to simply demonstrate that union members were also party members for the purpose of calculating convention delegate entitlement. Despite the fact that union affiliation did not require any per capita payments under this system, affiliation numbers continued to dwindle. In an effort to reverse this trend, delegates at the party’s 2021 convention passed a constitutional amendment granting union affiliates delegate positions (through national and/or local affiliation) based on the size of the union, rather than the number of card-carrying New Democrats who were also members of the affiliated union. Whether or not this change will lead to an increase in affiliation rates and reverse the union movement’s declining clout in the party remains to be seen. The impact of affiliation on key party decision-making processes, like leadership contests, however, has declined in recent decades given the gradual move towards a one-member-one-vote system.

Overall, while NDP union affiliation numbers never came close to meeting their potential, there is no question that union fundraising dollars and organizational ties that guaranteed labour representation in party structures ensured a close degree of cooperation between union leaders and the party in its first few decades. As the composition of the union membership changed and campaign finance laws became more restrictive, however, NDP-union relations were further weakened in the context of the party’s ideological shift away from its social democratic roots beginning, in earnest, in the 1990s.

Labour’s Ideological Impact

Even as distance has grown between organized labour and the NDP, and the financial link has been severely undermined in recent decades, the party’s opponents on the right continue to lambaste the party as the puppet of “unions bosses.”

But fear of an outsized role for labour also lingers within the party itself. A 2009 NDP member survey revealed that while a slim majority (54%) thought labour’s decision-making influence on the party should “stay the same,” 30% thought it should be decreased or greatly decreased, while only 16 per cent thought it should be increased or greatly increased.2 But what are the ideological implications of significant union influence on or within the NDP? The answer is not as straightforward as it may seem, in part because labour’s ideological influence on the party has never been uniform and has evolved over time.

The presence of union delegates tended to anchor the party in a pragmatic class politics rooted in defending workers’ institutional and economic interests as opposed to advancing transformative socialist or anti-capitalist agendas.

While labour has never been a monolithic ideological group, trade unionists were initially perceived by many longtime activists as a moderating influence within the party. In their survey of 1987 NDP convention delegates, Archer and Whitehorn reveal that non-union delegates were more likely than union delegates to identify as “socialist” and placed themselves further to the left than union delegates on a left-right scale.3 They also concluded that union delegates were less likely to embrace radical policy positions and were demonstrably less committed to equity politics and demilitarization. On the other hand, perhaps unsurprisingly, union delegates were more likely to support pro-labour policies that would advance union interests. For example, they were much more likely to oppose hypothetical NDP government intervention in the process of free collective bargaining or any kind of interference with the right to strike. Union delegates were also more likely to agree (60.8% vs. 52.5% for non-union delegates) that “the central question of Canadian politics is the class struggle between labour and capital.4 In other words, while the labour link seemingly reinforced a more explicit class-based approach to politics, it did not necessarily reinforce a more left-wing politics overall. Rather, the presence of union delegates tended to anchor the party in a pragmatic class politics rooted in defending workers’ institutional and economic interests as opposed to advancing transformative socialist or anti-capitalist agendas. Consequently, the labour presence within the NDP has sometimes worked to temper some of the more radical impulses of the party’s activist and social movement components.

However, important segments of the labour movement have also played the role of left-wing party critics at important moments in NDP history. After Bob Rae’s Ontario NDP government pushed through its infamous Social Contract Act – a fiscal austerity program that rolled back wages and suspended collective bargaining rights in the public sector – many unions came out swinging. In response to the Social Contract, the Ontario Federation of Labour’s 1993 convention voted to condemn “the Ontario NDP government for violating the principles of free collective bargaining” and called on the OFL and its affiliated unions to disaffiliate from the provincial party. The law’s passage had clearly alienated a majority of the province’s labour movement and led to a re-evaluation of the traditional link between organized labour and the NDP across the country. The crisis in social democratic electoralism precipitated by the Social Contract contributed to the party’s loss of the official party status in the 1993 federal election.

The party and the labour movement were undoubtedly estranged in the wake of the Social Contract, but the Federal NDP’s historic defeat did not precipitate an immediate divorce. The CLC waited until after the much anticipated defeat of the Rae government in 1995 to undertake a process of reviewing its relationship with the party. Although the CLC’s May 1996 report reaffirmed labour support for the NDP, it also insisted that the party must recognize labour’s special status as a founding partner and recommended more regular meetings between the NDP leadership and the CLC’s Executive Council. Even though the party was receptive to the report’s findings, most of the CLC’s affiliates were not nearly as willing as the Congress to forgive the NDP for its apparent ideological drift.

In Ontario, party-union divisions precipitated by the passage of the Social Contract led to a significant fragmentation in the electoral approach of unions. While some unions, after pointing to the lack of alternatives, remained steadfast allies of the ONDP, others embraced anti-Conservative strategic voting as a preferred electoral strategy. In most cases, that meant forging closer ties to the Liberals as the party best positioned to defeat Conservatives in the vast majority of ridings.

In 2003, the Ontario Liberals received more in union campaign contributions than the Ontario NDP. This historic first demonstrated the extent to which organized labour was willing to shift allegiances. While the Federal and Ontario sections of the party had always been forced to contend with the problem of strategic voting, the fact that some of the party’s traditional union allies were now backing strategic voting efforts caused enormous animosity between party officials and certain union leaders. In fact, Canadian Auto Workers (CAW) union President Buzz Hargrove’s endorsement of strategic voting in the 2006 Federal election led the Ontario NDP to revoke his party membership, thus precipitating an official break between the NDP and the CAW. This was a particularly significant fracture given the key role the union had played in both launching and bankrolling the NDP historically.

This “success psychology” continues to plague the NDP, both federally and in most provinces. However, it does help bolster the party in provinces where the NDP routinely forms government.

The CAW was not the only labour organization experiencing strained relations with the NDP during this period. The CLC and a host of labour leaders were critical of NDP leader Jack Layton’s decision to pull the plug on Paul Martin’s minority Liberal government in 2005 and trigger a federal election, leading a growing number of unions to embrace anti-Conservative strategic voting.

While the effectiveness of union-backed strategic voting campaigns are suspect at best, the electoral tactic has become normalized and widespread in labour movement circles, especially in Ontario and at the federal level where competitive multi-party systems have endured. Union-led anti-Conservative strategic voting has been framed by unions as a form of electoral harm reduction that prioritizes stopping Conservatives over a partisan focus on advancing the electoral standing of the NDP. While strategic voting campaigns have undoubtedly undermined the NDP in key jurisdictions in recent decades, it is important to remember that union leaders’ concerns about the party’s ability to win elections have always undermined the Federal NDP’s electoral prospects.

From the very start, what David Lewis referred to as “success psychology” hampered the party’s ability to secure union votes. Political scientist Gad Horowitz described the dilemma as follows: “Union support is necessary for the take-off; but the take-off is a prerequisite for support from these unions. Their leaders want to back a winner; they want some assurance of large profits before they make their investment.”5 Languishing in third or fourth place in public opinion polls for most of its history has undermined confidence in the Federal NDP’s ability to win. This “success psychology” continues to plague the NDP, both federally and in most provinces. However, it does help bolster the party in provinces where the NDP routinely forms government.

Delivering Union Votes

The labour leadership’s hesitancy to fully embrace the Federal NDP is both a product and a symptom of the relatively weak level of support the NDP receives from union voters. Over the years, several studies have addressed this question and have consistently highlighted the disconnect between union leaders and union members on the question of support for the NDP.

In 1976, Robert Laxer wrote that while provincial federations of labour, the CLC, and most large industrial unions officially backed the NDP, most union locals in Canada remained non-partisan or offered only “perfunctory” support to the party.6 Writing about the same period, historian Desmond Morton observed that “the few unions that found the courage and the cash to survey their own members’ attitudes soon discovered that few of them had any allegiance to the labour movement’s political or social goals nor even to their own elected leaders. Unions were strictly for benefits.”7

Decades later, when asked about the party-union relationship CUPE National President and future BC NDP MLA Judy Darcy, lamented that “the focus has been far too much on the organizational relationship at the top, and not enough on the common education that needs to be done with union members and people in Canada around the programs that the NDP and labour movement have in common.” Adding, “we’re not reaching our members with those issues between elections. It’s no wonder we’re not persuading them at election time.”8

While research consistently shows that union membership makes voters somewhat more likely to vote for the party, it is worth remembering that the Federal NDP has rarely secured a plurality of union member votes at election time. The 2011 federal election, in which the NDP formed the Official Opposition for the first time in history, stands out as the exception to the rule. However, in that election, the party garnered an unprecedented share of union votes despite dwindling formal union support.

This leads to the question of whether or not union endorsements carry much weight at all. Take the example of party’s historic breakthrough in Quebec under Jack Layton: the irony is that it occurred in spite of the provincial labour leadership’s overwhelming preference for the Bloc Quebecois (BQ) in that election. While the NDP’s slate of Quebec candidates included some union activists, most union leaders, and the Quebec Federation of Labour, were urging a vote for the BQ. Even after the NDP had overtaken the other parties in public opinion polls in the province, and were the odds-on favourite to secure the largest number of Quebec seats, the province’s labour movement stubbornly stuck with the Bloc and even attacked the NDP in the dying days of the campaign. The Quebec Director of the Steelworkers, for example, argued that the NDP would defend Ottawa’s interests at the expense of Quebec’s and warned that a vote for the NDP would split the vote and facilitate the election of Conservative MPs. A week later, the BQ lost official party status and the NDP made history. In the subsequent 2015 election, the province’s unions largely abandoned the Bloc as an electoral vehicle and rallied around the NDP, now led by Tom Mulcair, as the party best positioned to defeat the Harper Conservatives. After a lacklustre campaign, however, the NDP managed to hold on to just 16 of its Quebec seats.

In the 2015 federal election, union voters across Canada tended to abandon the party in greater proportion than their non-union counterparts, leading to speculation that union members’ votes were more likely driven by the fear of a Conservative government than strongly held pro-NDP views. In the 2025 federal election, this dynamic shifted as the NDP shed votes and seats to both the Liberals and Conservatives, resulting in the loss of official party status and its worst ever electoral performance.

An overreliance on polling and focus groups has seemingly transformed the NDP into an ideologically incoherent weathervane in search of the coveted moderate swing voter.

In his book, The New NDP, David McGrane argues that during the Layton years, the Federal NDP’s political marketing and locus of power shifted away from direct party stakeholders, like organized labour, towards party competitors and swing voters. This shift, he argues, had a moderating effect on the party as it abandoned class-based approaches to political organizing in favour of issues-based political micro-targeting driven by party insiders and staffers. According to McGrane, because the Federal NDP managed to increase its vote share and seat count in each election between 2000 and 2011, “in a virtuous circle, electoral success and moderation and modernization reinforced each other.”9 The irony of McGrane’s analysis, however, is that for most of the NDP’s history, organized labour had a demonstrably conservative or moderating effect on the party’s policies and ideological brand. Thus, the idea that loosening ties with labour helped contribute to even further moderation speaks then to the extent to which the party’s commitment to any semblance of social democratic politics has been compromised.

In response to focus groups and public opinion surveys, the party has, at times, gone out of its way to disassociate itself with class-based politics, opting instead to embrace a political marketing strategy that slices and dices the electorate into issue-based consumer-voters. An overreliance on polling and focus groups has seemingly transformed the NDP into an ideologically incoherent weathervane in search of the coveted moderate swing voter. This strategic gamble has largely come at the expense of a focus on politically organizing and mobilizing working-class voters for the purpose of building sustained support for positions and policies that will redistribute power and wealth in meaningful ways. While the slate of federal NDP candidates has always included a good number of local union leaders, staffers, and activists who continue to consider the NDP to be “their” party, the party can no longer credibly be described as the political arm of the labour movement.

For their part, labour organizations are more active than ever in electoral politics. But they have largely migrated to ad hoc strategic alliances with a variety of parties, strategic voting campaigns, third party advertising, or parallel issue campaigns as ways of educating and mobilizing members. The efficacy of some of these tactics requires further examination, but what is clear is that most unions continue to struggle with meaningful member engagement as it relates to political parties and elections, and certainly do not engage in the type of political education that Judy Darcy had called for.

The Future of Labour and Working-Class Politics in Canada

Unprecedented union endorsements and increased working-class support for the Conservatives in Ontario and federally suggests that the NDP’s strategic reorientation away from organized labour as a formal partner has opened real opportunities for other parties to compete for the labour vote.

While the Liberals have always made an effort to cut into the NDP’s labour and working-class base, Conservatives have more recently begun to pursue populist frames and strategies designed to win over union voters traditionally hostile to that party’s anti-labour policy positions. There is evidence that the Conservative strategy is working, especially among male blue-collar private sector union workers.10

The Conservative case for private sector unions, steeped in populist rhetoric, is designed to exploit fissures between private and public sector workers by positioning the party as a catalyst for private sector growth and opportunity, on one hand, and public sector restraint on the other. Conservatives decry economic inequality, but in a way that lays blame not on capitalism as an economic system, but rather foreign actors and greedy elites. In short, the Conservatives are using populist and conservative cultural appeals to address the very real material concerns of union members in a way that clearly differentiates them from other parties more closely associated with the promotion of working-class interests.

In the aftermath of the Federal NDP’s disastrous 1993 campaign – the only other time the party lost official status – unions played a key role in sustaining the party financially and through research support. That investment paid off when the party managed to regain status in 1997. But because of campaign finance changes, unions cannot play the same role in the wake of the 2025 result. Even if they could, the level of ambivalence towards the party from segments of organized labour should concern party leaders.

The NDP’s ability to credibly advance this alternative vision depends largely on whether the labour movement is itself willing and able to engage in such political and economic education.

A good number of left-wing union activists view the NDP as an unreliable electoral vehicle to achieve a social democratic government, even on its own terms. The ghosts of Bob Rae and other unpopular provincial NDP premiers loom large here, but this does not absolve labour leadership from its shared responsibility for the sorry state of working-class politics in Canada.

The labour movement has also drifted politically, lowering its expectations in the face of a crisis in social democracy, and showing little interest in pursuing political alternatives that might challenge the fundamental pillars of Canada’s labour relations regime, let alone the broader capitalist economic system. Some unions continue to steer clear of parties and elections altogether, insisting that talk of politics has no place in the union, thus reinforcing the status quo. Even among those unions who embrace political action, democratic socialist political education is largely absent from labour education courses, which focus primarily on the technical and legal aspects of labour relations, rather than the labour movement’s political vision or potential.

Union density, particularly in the private sector, has experienced steep declines, and the labour movement’s capacity to mount effective and sustained fight back campaigns has taken a similar hit. Where unions have become more politically active, electoral engagement has tended to be transactional in nature, as labour organizations have grown increasingly defensive in the context of right-wing restructuring. The drift towards strategic alliances with Liberals or Conservatives by important segments of the labour movement, then, should be understood as a sign of organized labour’s weakness rather than strength.

If the crisis in social democratic electoralism is breathing new life into transactional approaches to electoral politics, what does this mean for the future of labour and the NDP? Given that a formal institutional rapprochement between unions and the NDP appears increasingly unlikely, cooperation may take on more informal dimensions. Over time, however, as historical attachments wither, union density declines, and personalities in key decision-making positions change, we can expect the NDP-union link will erode even further unless conscious decisions are made to turn things around.

No amount of finger-wagging by NDP activists will bring unions back to the fold. In fact, that approach is likely to be counterproductive. While it’s too early to tell if Conservative appeals to union voters will lead to a sustained electoral realignment, it’s clear that the NDP’s weakening ties to the labour movement have invited such strategic interventions from the right. Of course, this dynamic is not unique to Canada. Right-wing populist frames have helped to construct an alternative narrative about the sources of economic insecurity, and the solutions needed to bring back working-class prosperity, in different national contexts.

The challenge for both the NDP and the labour movement is to contest the legitimacy of such frames – not by dismissing the intended audience as stupid or ignorant – but rather by putting forward an alternative vision and understanding of the economy that directly addresses their material interests in ways that unite workers through shared class interests. This undoubtedly requires a great deal of education, but it also requires organizing and clear messaging about the shortcomings of capitalism as a system that produces and reproduces the very economic, social, and racial inequalities that stratify and divide working-class communities. The NDP’s ability to credibly advance this alternative vision depends largely on whether the labour movement is itself willing and able to engage in such political and economic education.

Notes

- Harold Jansen and Lisa Young, “Solidarity Forever? The NDP, Organized Labour, and the Changing Face of Party Finance in Canada,” Canadian Journal of Political Science 42, 3 (2009): 664. ↩︎

- Linda Erickson and Maria Zakharova, “Members, Activists, and Party Opinion,” in Laycock and Erickson, Reviving Social Democracy, 178. ↩︎

- Keith Archer and Alan Whitehorn, Political Activists: The NDP in Convention (Toronto: Oxford University Press, 1997), 54. ↩︎

- Archer and Whitehorn, Political Activists, 59. ↩︎

- Gad Horowitz, Canadian Labour in Politics (Toronto: University of Toronto Press, 1968), 262. ↩︎

- Robert Laxer, Canada’s Unions (Toronto: James Lorimer & Company, 1976), 263. ↩︎

- Desmond Morton, Working People: An Illustrated History of the Canadian Labour Movement 4th ed. (Montreal: McGill-Queen’s University Press, 1998), 315. ↩︎

- Ian McLeod, Under Siege: The Federal NDP in the Nineties (Toronto: James Lorimer & Company, 1994), 129. ↩︎

- David McGrane, The New NDP: Moderation, Modernization, and Political Marketing (Vancouver: UBC Press, 2019), 41. ↩︎

- Daniel Westlake, Larry Savage, and Jonah Butovsky, “The Labour Vote Revisted: Impacts of Union Type and Demographics on Electoral Behaviour in Canadian Federal Politics” Canadian Journal of Political Science, 58:3 (2025):642-665. ↩︎