Listen to an interview with Marc-André Gagnon for more on Pharmacare on the Perspectives Journal podcast, available to subscribe on Spotify, Apple Podcasts, YouTube, Amazon Music, and all other major podcast platforms.

Introduction

The provision of prescription drugs is typically a fundamental component of national health care systems, often viewed as an essential health service. Notably, every OECD country with universal health care covers prescription drugs, except Canada. (ACINP 2019) The concept of “Pharmacare” — public drug coverage distinct from universal health coverage (Medicare) — is a Canadian specificity. Although all provinces and territories offer some level of public drug coverage for non-working populations, such as seniors and those on social assistance, the majority of Canadians receive drug coverage through private benefits provided by employers. Consequently, access to medicines is still conceived of as privileges offered by employers to employees.

Public drug coverage in Canada is characterized by a fragmented system comprised of numerous drug plans designed to aid individuals without access to private insurance. This fragmentation results in many Canadians falling through the gaps and struggling to access necessary medications. Since 2015, the debate around reforming public drug coverage has intensified, and significant reforms are gradually being implemented.(Adams & Smith, 2017; Boothe, 2018; Flood, Thomas, & Moten, 2018; Gagnon, 2021) This paper outlines the current structure of drug coverage in Canada, evaluates its outcomes regarding access and costs, explores the ongoing debates and recent federal legislation aimed at introducing universal pharmacare, and, more specifically, explains why progressive amendments were called for before the passing of Bill C-64; An Act Respecting Pharmacare.

1. The Structure of Drug Coverage in Canada

Universal healthcare in Canada was first introduced in Saskatchewan by Premier Tommy Douglas in 1947 and, following the recommendations of the Royal Commission on Health Services (commonly referred to as the “Hall Commission”) in 1964, it was extended to the rest of Canada in the early 1970s based on a financial arrangement between the federal government and the provinces: the federal government provides financial transfers to the provinces if they offer universal healthcare coverage that respects specified standards defined in federal legislation. In 1984, the Canada Health Act (CHA) established the current set of standards, requiring that health insurance be universal, publicly administered, portable across provinces, comprehensive and accessible without direct charges to patients. (Marchildon, 2021) However, the CHA does not cover all medically necessary healthcare services; it is limited to coverage of medically necessary hospital and physician services only. (Fierlbeck, 2011, pp. 89). While medicines used in hospitals are totally publicly financed in accordance with the CHA, there are no standards for the coverage of prescription drugs outside of clinical healthcare institutions.

As a consequence, access to prescription drugs in Canada relies on a confusing patchwork of over 100 public drug plans and over 100,000 private plans (ACINP 2019). Each plan, public or private, has a variety of premiums, co-pays, deductibles or annual limits, creating critical discrepancies in the way a Canadian citizen may be covered, depending on where they live or where they work. The objectives of drug plans also vary: while public drug plans aim at maximizing health outcomes by funding cost-effective treatments, many private plans are designed for employers to find a middle-ground with employees during collective bargaining, without a clear understanding of the health needs of the employees, and with the principle value that a good drug plan covers anything at any price. (O’Brady, Gagnon, & Cassels, 2015)

1.1 TYPES OF DRUG COVERAGE

Drug coverage in Canada falls into four main categories:

PROVINCIAL AND TERRITORIAL PUBLIC DRUG PLANS

Provincial and territorial (PT) public drug plans account for 39 percent of prescription drug expenditures, (Canadian Institute for Health Information, 2023) but vary widely across jurisdictions. (Canadian Institute for Health Information, 2024) All PTs cover seniors and social assistance recipients. Coverage for social assistance recipients is generally consistent, while coverage for seniors can vary, and is often income-tested. (Daw & Morgan, 2012) Some provinces offer catastrophic coverage for high drug costs that households have hard time paying, with deductibles ranging from 3 percent to 20 percent of annual income, and co-pays between $2 and $30 per prescription. (Brandt, Shearer, & Morgan, 2018) Some PTs offer coverage for specific diseases, or for substance use, and others also provide coverage for children or for low-income people. (Canadian Institute for Health Information, 2024)

FEDERAL PUBLIC DRUG PLANS

The federal government covers prescription drugs for First Nations people and Inuit, through the Non-Insured Health Benefits (NIHB) program that covers the costs of prescription drugs not covered by a private drug plan. The federal government also provides coverage for refugees, military personnel, RCMP members, and federal prisoners. (Fierlbeck & Marchildon, 2023). This coverage represents only 3 percent of total drug expenditures in Canada. (Canadian Institute for Health Information, 2023) Public expenditures for drugs in Canada (by provinces, territories and the federal government) are notably low compared to other OECD countries considering that only Poland, Bulgaria and Chile have a lower percentage of public expenditure. (OECD, 2023, pp. 199)

PRIVATE DRUG PLANS

Private drug plans, mainly provided by employers, cover 37 percent of total drug expenditures. (Canadian Institute for Health Information, 2023) Most private drug plans are provided by employers as extended health care benefits. This type of drug insurance pools the risks of all those in the same given workplace. Private premiums for drug coverage can thus be different from one workplace to the next. When private employer provided plans that offer similar drug coverage are compared, it has been found that in workplaces where employees tend to be older, poorer, or less healthy, premiums are significantly higher than in workplaces with younger, richer, or healthier staff. (Gagnon, 2014)

Large employers often use “administration services only” (ASO) plans, where the insurance company administers the plan, but does not assume risk. Under this scheme, the insurance company earns a percentage of spending administered through the drug plan. This creates a situation where private insurance companies have no incentive to reduce the structural costs of prescription drugs. Smaller employers usually opt for “fully insured” plans where, for a higher fee, the private insurance company covers the risks. It is possible, therefore, that the given insurance company may spend more to cover risks than what it receives in premiums. However, for fully insured plans, premiums received by the insurance company are normally adjusted yearly to cover the amount in reimbursement spent the year before, to which an additional mark-up is added.

As higher spending means higher premiums with a constant mark-up rate, private insurance companies providing fully insured plans also have no incentive to reduce structural costs for prescription drugs. (Gagnon, 2014) Administration costs, included in the determination of the level of premiums, are not accounted for in the cost of prescription drugs, but they can become quite significant: administration costs for private drug plans are normally between 13 percent and 23 percent in Canada, (Law, Kratzer, & Dhalla, 2014; Himmelstein, Campbell, & Woolhandler, 2020) while they vary between 1 percent and 2 percent for public drug plans. (Gagnon, 2014; Régie de l’Assurance-Maladie du Québec, 2023)

Smaller employers are getting very concerned about the sustainability of their drug benefits, especially considering that many new drugs arriving on the market have very expensive price tags. (Charbonneau & Gagnon 2018) Their concerns are valid; for example, if a firm employs 50 employees, and an employee’s family member starts requiring a drug treatment that costs $200,000 annually, then private premiums for each employee of that workplace could see increases of up to $4,000 annually once premiums are adjusted.

Private drug plans are incentivised by both federal and provincial governments (except Quebec) through significant tax subsidies, since the premiums paid for private drug benefits are excluded from taxable annual income. This creates significant equity issues as high income individuals (with a higher marginal income tax rate) then come to receive higher public subsidies for private drug coverage than low-income individuals. Private drug plans have become reliant on governments, considering that 30 percent of the expenditures by private drug plans are used for the private coverage of public employees, and tax subsidies offered by federal and provincial governments represent around 25 percent of the total cost of private drug plans. (Gagnon, 2012)

OUT-OF-POCKET EXPENDITURERS

Canadians spend 20 percent of drug expenditures out-of-pocket, either due to co-pays or deductibles when the person has public or private coverage, or because the person has no coverage at all. (Canadian Institute for Health Information, 2023) The government provides a non-refundable tax credit of 15 percent for out-of-pocket medical expenses, including prescription drugs, exceeding a means-tested threshold. (Gagnon, 2012) Financial barriers can lead to non-adherence to prescriptions, impacting health outcomes and increasing overall costs. (Hennessy, et al. 2016; Gagnon, 2017)

1.2 VARIATION IN PROVINCIAL COVERAGE

While provincial health systems do provide some coverage to those without private drug coverage, there is a lot of variation between the provinces in terms of who they cover, how those eligible are covered, which drugs are covered, and the extent to which patients must pay out-of-pocket. (Demers, et al., 2008; Campbell, et al., 2017) To illustrate this variation between provinces, we can compare three provincial plans: Ontario, Quebec and Prince Edward Island (PEI). The first two are the most populous provinces while PEI, the smallest provinces, has the most complex patchwork of public drug plans. In these three provinces, private drug plans cover the majority of the population, and provincial public drug plans are designed to support those without private coverage.1

Ontario

Around 40 percent of the Canadian population lives in Ontario. (Statistics Canada, 2024) In Ontario, public drug plans cover the non-working population, specific diseases and treatments, as well as universal catastrophic coverage for people who spend over a certain threshold of their annual income on prescription drugs. In total, there are eleven different provincial public drug plans in Ontario:

The Ontario Drug Benefit Program (ODB) is made of three different programs for which a means-tested deductible and co-pay (up to $8.11 per prescription) can be required. These programs cover three vulnerable groups, including: seniors (65 years old and older); low-income people receiving social assistance; and residents of long-term care homes. ODB also provides first-dollar coverage to people 24 years old and younger, not covered by a private drug plan.

The Trillium Program is another scheme that provides drug coverage to Ontario residents whose drug costs are elevated in comparison to their annual household income. Once the deductible of 4 percent of the annual income is reached, those insured by the Trillium Program pay $2 per prescription. Other programs cover specific diseases or treatments such as inherited metabolic diseases, respiratory syncytial virus, intravenous cancer drugs, Visudyne, and some select high cost drugs. Because of catastrophic drug coverage offered by the Trillium Program, it is possible to say that all Ontarians have access to some form of drug coverage. However, because of the high deductibles entailed, financial barriers to access drugs in Ontario still exist for a significant share of the working population.

QUEBEC

Quebec is the second most populous province with around 22% of the Canadian population based in the province (Statistics Canada 2024). In 1997, Quebec implemented a private-public system of drug coverage designed to ensure that all residents have drug coverage (Morgan et al. 2017). The system upholds the primacy of private drug coverage, which is mandatory for employees and their dependents when a private drug plan is available. Employers who want to offer health benefits to their employees must include prescription drugs, and employees cannot refuse unless they already have a private drug plan through their spouse or a different employer. Certain conditions apply both to public and private drug plans: all drugs covered by the public plan must be covered by private drug plans; monthly deductibles are limited to $22; the co-insurance rate is limited to 32%; and total annual out-of-pocket payments for insurees must not exceed $1,196.00 (Régie de l’Assurance-Maladie du Québec 2024).

Because private drug plans are mandatory, Quebec is the only province that does not provide tax subsidies as incentives for employers to provide drug benefits. For Quebec residents who cannot access private coverage, they are automatically covered by a public drug plan. Quebec’s Public Prescription Drug Insurance Plan covers 4 different groups:

- Those who are 65 or over automatically have access to the public prescription drug insurance plan. Every senior without a private plan is covered by the public plan, and even if a private drug plan is available, it is not mandatory anymore for this age group, who can simply access the public plan instead. The conditions mentioned above apply (with lower annual maximal amounts to be paid out-of-pocket), and an income-based premium is also required, up to $744/year (Régie de l’Assurance-Maladie du Québec 2024).

- Social assistance beneficiaries are also automatically covered, without any premium or out-of-pocket expenditures.

- Anyone under 65 without access to a private drug plan is automatically covered. The conditions mentioned above apply, and an income-based premium is also required, up to $744/year (Régie de l’Assurance-Maladie du Québec 2024).

- Children under 18 (or under 25 if they attend an educational institution at full-time) without access to a private plan are covered, without any premium or out-of-pocket expenditures.

The Quebec public prescription drug insurance is often considered an ideal model since every Quebec citizen has private or public coverage. However, it is not actually a universal program, because how coverage is applied, access to different drugs, and deductibles and co-pays vary between individuals. In fact, in many ways, the system is designed to artificially increase the costs of private plans, for example by imposing higher dispensing fees and prices for private plans, while using measures to contain costs for the public drug plan (Gagnon et al. 2017).

PRINCE EDWARD ISLAND

Making up less than 0.5 percent of the Canadian population, Prince Edward Island (PEI) is the smallest Canadian province by population. (Statistics Canada, 2024) PEI Pharmacare is the payer of last resort for eleven public drug programs delivered through retail pharmacies, and for fourteen public drug plans delivered through a centralized provincial dispensary called Provincial Pharmacy. The latter public drug plans are built around specific diseases or products, including drugs or vaccines for HIV/AIDS, hepatitis, cystic fibrosis, immunization, rabies, tuberculosis, and more.

The eleven public drug plans delivered through retail pharmacies serve diverse needs and include programs for seniors and children. There are also specific pharmacare programs for catastrophic drug needs, high-cost drugs, diabetes and insulin pumps, generic drugs, as well as nursing homes, home oxygen, smoking cessation drugs and sexually transmitted diseases.

PEI’s variety of public drug plans, all with different types of co-pays for such a small population, is indicative of the complexity of the current system of drug coverage. All of PEI’s programs depend on specific diseases, conditions or age. The catastrophic drug program appears to be an exception as it is accessible to all who find themselves in financial hardship. In all cases, however, PEI’s drug plans maintain an annual deductible of up to 6.5 percent of annual income, based on total household income.

1.3 PROBLEMATIC ACCESS

In addition to the technical complexity of public and private drug plans, requisite deductibles, co-insurance rates, and co-pays can introduce significant financial barriers to access to prescription drugs by imposing out-of-pocket expenditures. 21 percent of Canadians report having no drug coverage, and around 10 percent of the population reports not filling their prescription(s) or skipping doses because of financial barriers. (Cortes, Smith & Leah, 2022). The majority of those without coverage or incapable of accessing their drugs are low-income workers, (Bolatova & Law 2019; Barnes 2015) as well as racialized Canadians and migrants. (Cortes, Smith & Leah, 2022)

The financial hardships suffered by Canadians due to lack of coverage or insufficient coverage must not be downplayed: many Canadians end up having to decide between buying medications or food, (Patel, et al., 2016; Men, et al., 2019) or have to shrink their spending on housing, transit, or cell phone plans. (Goldsmith, et al., 2017) Removing financial barriers to access prescription drugs could prevent hundreds of deaths every year, as well as thousands of hospitalizations. (Lopert, Docteur, & Morgan, 2018) For many types of disease, non-adherence to treatments due to financial barriers ends up costing more to the public through expensive emergency room visits and hospitalizations, when first-dollar public coverage for the drugs would have been a more efficient use of public health expenditures. (Persaud, et al. 2023; ACINP, 2019, pp. 47) When compared to countries surveyed by the Commonwealth Fund’s International Health Policy Survey, Canada remains a laggard when it comes to access to prescription drugs (see Table 1).

Table 1 — Percentage of population not filling prescriptions or skipping doses because of cost

| Country | Percentage (%) |

|---|---|

| Netherlands | 4.5 |

| France | 5.0 |

| Sweden | 6.4 |

| United Kingdom | 7.2 |

| Germany | 7.3 |

| New Zealand | 7.4 |

| Switzerland | 8.5 |

| Canada | 10.4 |

| Australia | 13.0 |

| United States | 20.9 |

1.4 THE HIGH COSTS OF PRESCRIPTION DRUGS IN CANADA

Canada’s prescription drug costs are among the highest globally. In 2023, Canadians spent approximately $41.1 billion on prescription drugs. (Canadian Institute for Health Information, 2023) This amount excludes another $6.7 billion spent on drugs and health supplies sold over-the-counter (almost fully paid out-of-pocket). Prescription drugs represented only 6.4 percent of health expenditures in 1985, and now represents 12 percent of health expenditures, which is more than the total amount spent for physician visits. (Canadian Institute for Health Information, 2023). Pharmaceutical sales in Canada represents 1.5 percent of Canadian GDP and 2.2 percent of the global pharmaceutical market, making Canada the 8th largest world market. (Innovation, Science and Economic Development Canada, 2024)

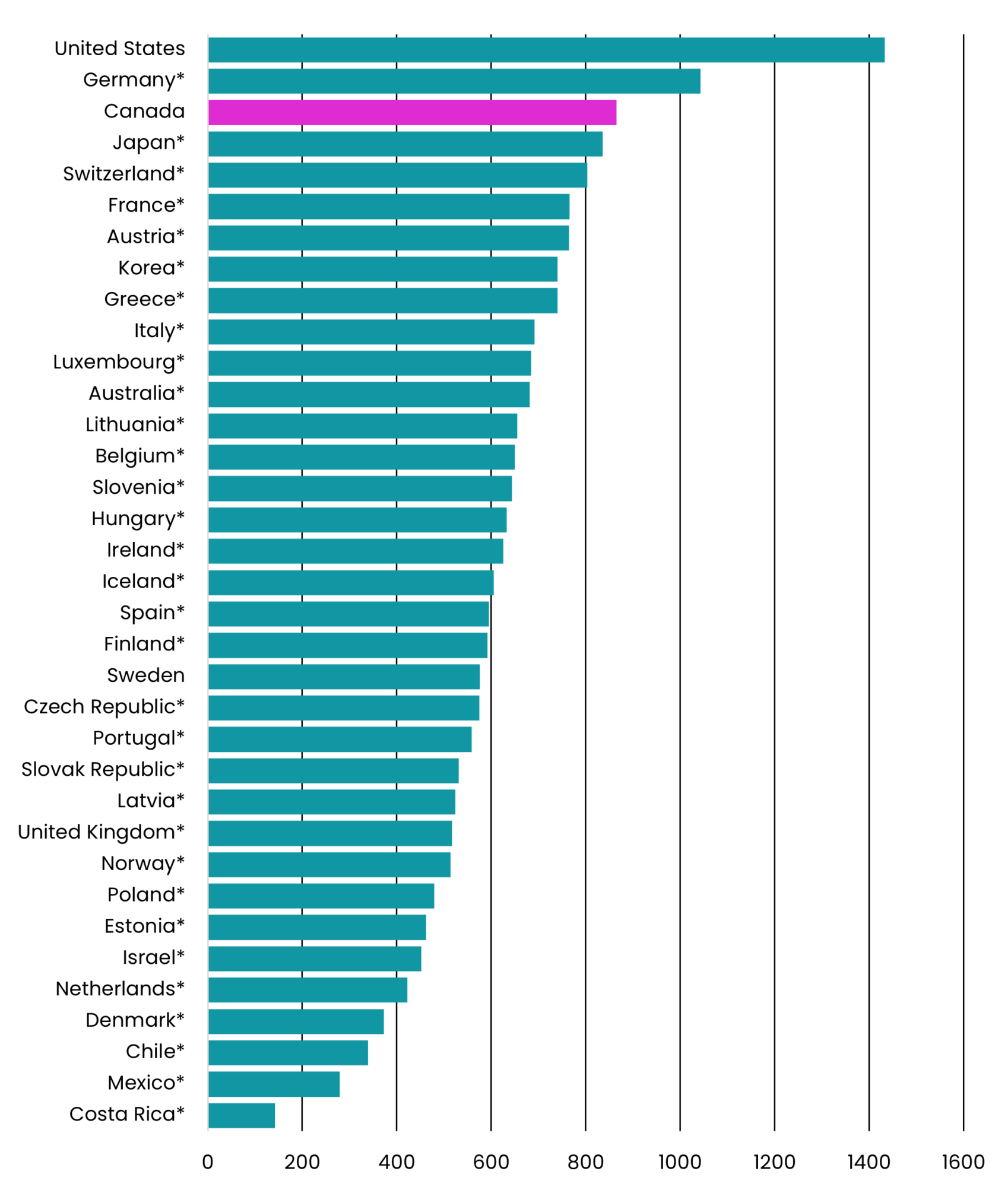

The cost per capita for prescription drugs in Canada is also among the highest worldwide. Canadians spend more than twice as much per capita as compared to their counterparts in the Netherlands or Denmark. When compared to other OECD countries, Canada is third in terms of cost per capita after the United States and Germany. In Germany, this per capita expenditure is notable as it includes a value added tax of 19 percent (See Chart 1).

Canada is characterized by both high costs per capita for prescription drugs and a significant proportion of the population who cannot access the drugs they need. This situation is due to high prices and a lack of cost efficiency.

Chart 1 — Total Expenditure on Pharmaceutical Goods per Capita, OECD, 2021 (or last year reported)

$USD Purchasing Power Parity

HIGH OFFICIAL PRICES

The first reason for high costs of prescription drugs in Canada is the high prices of patented drugs. When a new drug comes to the market, it is branded and patented. Once the patent expires, 20 years after the discovery of the molecule, generic competitors can enter the market and compete against the brand-name (but now unpatented) drug. While brand-name drugs normally maintain the high price of the drug as when it was patented, generics are normally sold between 8 percent and 25 percent of the price of the brand-name drug. Patented drugs represent around half the Canadian market in terms of sales, while unpatented brand-name drugs and generics each represents around a quarter of the market in terms of sales. (Patented Medicines Price Review Board, 2024, pp. 27).

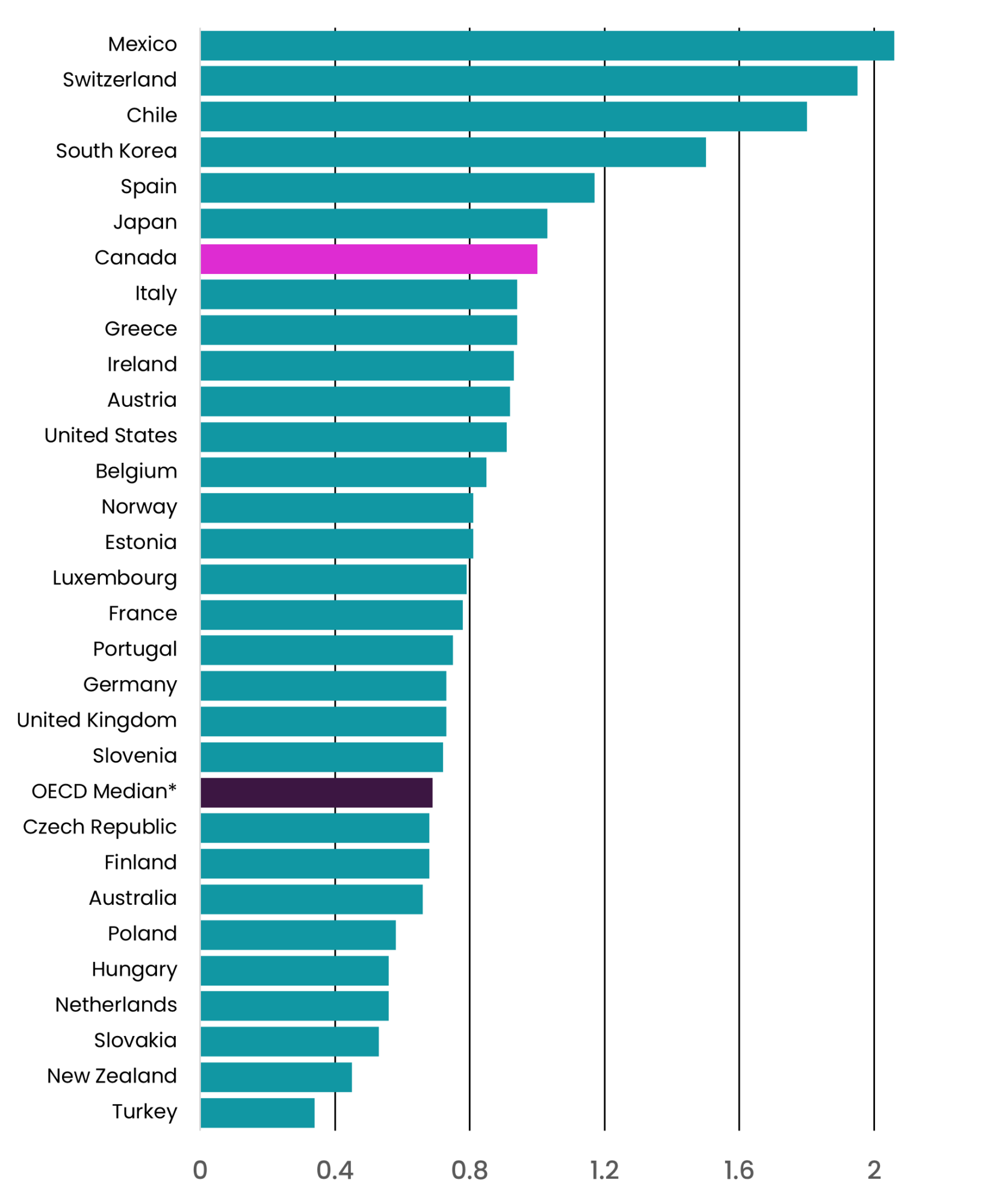

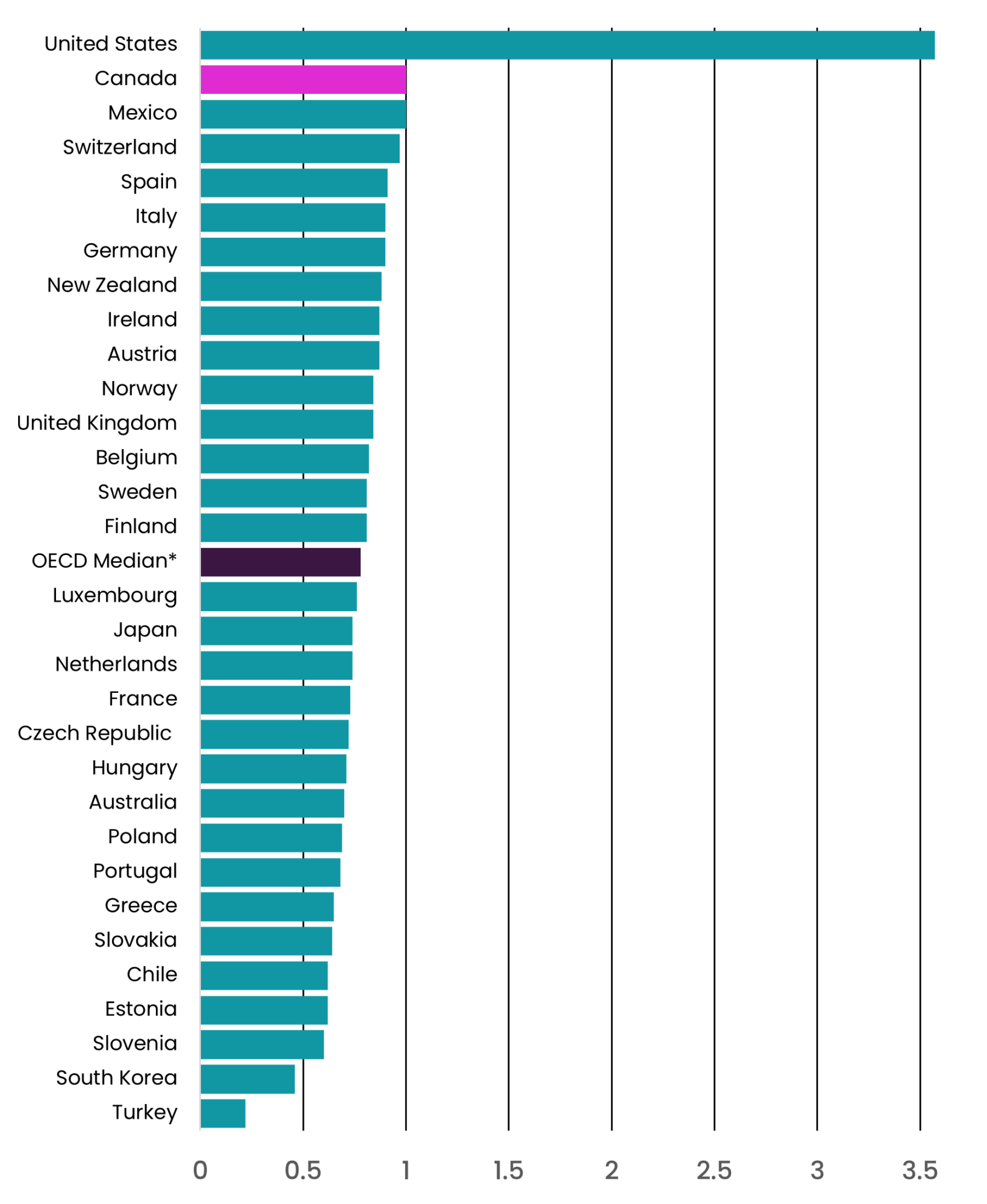

When it comes to the retail market, generics represent 78.6 percent of the market in volume, which is among the highest rates when compared with other OECD countries, but it represented only 22.8 percent of retail market in terms of value. (OECD, 2023, pp. 205) The price of generics in Canada is considered high when compared to other OECD countries, with the Canadian average price being 45 percent more expensive than the OECD median. (Patented Medicines Price Review Board, 2024, pp. 53) As for the price of patented drugs, Canada is the world’s second most expensive countries with prices 28 percent more expensive than the OECD median (see Chart 2 & Chart 3). (Patented Medicines Price Review Board, 2024, pp. 51)

Chart 2 — Foreign-to-Canadian Price Ratios for Generic Medicines, OECD, Q4-2022

Source: MIDAS ® database, October — December 2022, IQVIA (all rights reserved) [NPDUIS Report: Generics360, 2018 — graphs updated to 2022]

Foreign-to-Canadian Price Ratios for Generic Medicines

Chart 3 — Foreign-to-Canadian Price Ratios for Patented Medicines, OECD, Q4-2022

Source: Patented Medicines Price Review Board; MIDAS ® database, 2022, IQVIA (all rights reserved)

Foreign-to-Canadian Price Ratios for Generic Medicines

LOW CONFIDENTIAL REBATES

When analyzing the cost of patented drugs, it is crucial to recognize that the comparison of prices between countries can be misleading because the global pricing model for patented drugs includes additional layers of complexity. The official prices of patented drugs (which are the prices compared in Chart 3) are normally not the prices paid by drug plans, because most payers negotiate confidential rebates, which are not publicly disclosed. It is estimated that the confidential rebates obtained by public drug plans is normally between 20 percent and 29 percent of the official price. (Morgan, Vogler, & Wagner, 2017) In Canada, public drug plans collectively negotiate these rebates through the Pan-Canadian Pharmaceutical Alliance (PCPA), which includes all provincial, territorial, and federal public drug plans. The PCPA successfully secures approximately $3.9 billion in confidential rebates annually. This level of rebate is comparable to that achieved in other OECD countries. However, almost all OECD countries have a universal pharmacare system and negotiate confidential rebates for their whole population. In Canada, the PCPA negotiates confidential rebates for public drugs plans only, which represent only 42 percent of expenditures. Note that people insured through public drug plans still pay their co-insurance rates and deductibles, based on the official price of. drugs.

Private drug plans, on the other hand, have a more fragmented approach to negotiating confidential rebates. The prevailing culture within private insurance tends to prioritize broad coverage of approved drugs without substantial negotiation for rebates. (O’Brady, Gagnon & Cassels, 2015) Sun Life, as a private insurance company, is considered to be the most active insurer in negotiating rebates. (20Sense, 2022) Sun Life reported securing $500 million in rebates from 2014 to 2023, or an average of $56 million secured annually. (SunLife 2023) The negotiation of rebates, however, is not uniformly practiced across the industry. (Barkova & Malanik-Busby, 2023, pp. 38) Even if the rebate levels achieved by Sun Life were extended throughout the entire private sector, they would still represent only a fraction of what is obtained by public drug plans. Furthermore, there is no assurance that these rebates benefit the insured individuals, rather than the insurers’ shareholders. The lack of transparency in private rebate negotiations raises concerns that insurers might prioritize more expensive drugs with higher rebates, rather than cost-effective drugs that offer the best therapeutic value, as is observed in the United States. (Robbins & Abelson, 2024; Federal Trade Commission, 2024)

Not only do Canadians pays higher official prices than other OECD countries as the poor performance of private drug plans in negotiating confidential rebates contributes to higher costs, Canadians also pay even higher real post-rebate prices for the same prescription drugs when compared to other OECD countries (this is even before including the additional 10% mark-up in administrative fees paid in premiums for private plans, as compared to universal public systems). The fragmentation of drug coverage creates significant inefficiency when it comes to negotiating drug prices in Canada.

A more effective approach could involve organizing bulk purchasing and negotiating rebates for all Canadians through institutions that ensure that rebates are transferred to insurees. While it does not necessarily require a single-payer model, it does require that all payers accept to reimburse only drugs listed on a national formulary after agreeing on a cost-efficient price. Systematically negotiating drug prices based on their therapeutic value to ensure value-for-money could save billions in drug costs to Canadians. The Parliamentary Budget Officer has estimated that a universal pharmacare program with minimal co-pays could increase prescription drug utilization by 13.5 percent and reduce overall drug costs by $2.2 billion annually. (Barkova & Malanik-Busby, 2023) This would ensure more cost-effective and equitable access to medications for Canadians.

Canada’s drug coverage system is complex and fragmented, leading to significant disparities in access and affordability. The whole system seems currently designed to artificially increase costs for patients and employers without improving the health care Canadians are getting. Addressing these challenges requires comprehensive reform to ensure equitable access to medications for all Canadians, reducing financial barriers, and achieving cost-efficiency in drug pricing. Important debates have existed for decades about the necessity to reform the current drug coverage system. It is important to understand these debates to better grasp what is at stake with the passing of Bill C-64 An Act Respecting Pharmacare during the fall 2024 session of Parliament.

2. The Battle for Universal Pharmacare: A Historical and Political Overview

Canada’s journey towards universal pharmacare has been shaped by various federal commissions and political changes over the decades. The Hall Commission of 1964, formally known as the Canada Royal Commission on Health Services, recommended the inclusion of prescription drugs to a Canadian universal healthcare coverage. (Canada Royal Commission on Health Services, 1964) Two other significant federal commissions highlighted the need to include prescription drugs in a universal health care program. The National Forum on Health, in 1997, recommended first-dollar coverage for all prescription drugs, emphasizing a comprehensive approach to medication access. (National Forum on Health, 1997) Similarly, the 2002 Commission on the Future of Health Care in Canada, commonly referred to as the Romanow Commission, advocated for a universal catastrophic drug plan as an initial step towards universal pharmacare. (Commission on the Future of Health Care in Canada, 2002) The Romanow Commission also recommended establishing a national formulary, a national health technology assessment system to systematically obtain value for money, and a national drug purchasing and price setting system. (Commission on the Future of Health Care in Canada, 2002) All these policies developed over the past several decades would have been building blocks for a universal pharmacare system. (Gagnon, 2014)

In 2004, the Liberal Party of Canada-led federal government initiated a ten-year National Pharmaceutical Strategy (NPS) in agreement with the provinces and territories, aiming to implement the Romanow Commission’s recommendations. However, the Conservative Party’s victory in the 2006 federal election led to the abandonment of many of these initiatives, apart from extending the health technology assessment capacity of the Canadian Agency for Drugs and Technology in Health (CADTH). Notably, the proposed national catastrophic drug coverage system was discarded under Prime Minister Stephen Harper’s government. (Morgan, et al., 2016)

Since the 1990s, most provinces and territories made only minor adjustments to their public drug coverage systems. Quebec was a notable exception, implementing its own version of pharmacare in 1997, which required mandatory private drug plans. (Gagnon, et al., 2017) Ontario also took a significant step in January 2018 by introducing a universal pharmacare program for individuals under 25. However, this initiative was reversed later that year with the election of Doug Ford’s Progressive Conservative Party of Ontario to government, which limited coverage to those without private insurance. (Miregwa, et al., 2022)

2.1 RE-OPENING THE DEBATE (2015)

The election of the Liberal Party of Canada to the federal government in 2015 revived discussions about reforming drug coverage. The rising costs, accessibility issues, and sustainability concerns surrounding both public and private drug plans intensified calls for reform.

On one side of the debate, stakeholders such as private insurers, pharmaceutical companies, and pharmacy chains supported maintaining the existing patchwork of public and private plans, advocating for merely “filling the gaps” to assist those unable to access necessary medications. (Gagnon, 2021) Conversely, unions, consumer organizations, community groups, and over 1,000 Canadian health professionals and experts in health care and public policy pushed for a comprehensive overhaul of the patchwork, and for the implementation of a universal pharmacare system for all Canadians instead. (Pharmacare 2020, 2022) These proponents see a universal pharmacare system as not only a way to reimburse bills and provide access to those who cannot otherwise afford treatments, but also as a building block for putting in place the institutional capacity necessary for a more rational system that could reduce costs, provide value-for-money, and reduce overtreatments by ensuring that the prescribing habits of health care professionals are based on best available evidence, and not by manufacturers’ promotional campaigns. (Morgan, et al., 2016)

A report commissioned by the Standing Committee on Health of the House of Commons in 2016, and published in 2018, endorsed the implementation of universal pharmacare in Canada. (Casey, 2018) Studies suggested that such a system could not only improve access to prescription drugs in Canada, but could also save between 10 percent and 40 percent of current costs (Gagnon & Hébert, 2010; Morgan, et al., 2015) This was further corroborated by a 2017 report from the Parliamentary Budget Officer. (Malanik-Busby, et al., 2017) The central issue of cost-saving is contentious, as savings for Canadians translate into lost income for drug manufacturers, private insurers, and pharmacy chains, leading these stakeholders to, unsurprisingly, resist changes and advocate for a gap-filling approach. (Gagnon, 2021)

2.2 HOSKINS REPORT (2019)

In February 2018, the Government of Canada established the Ad- visory Council on the Implementation of National Pharmacare (ACINP), chaired by former Ontario Health Minister Eric Hoskins. The Council was tasked with developing an implementation plan for a National Pharmacare program. However, there was significant pressure from the Liberal Party to recommend a “fill the gaps” model rather than a complete overhaul (Blatchford 2018; Forrest 2018).

In 2019, the ACINP released its final report, commonly known as the “Hoskins Report,” which argued that a fill-the-gap approach was unsustainable. Instead, it proposed a model for implementing universal pharmacare and offered a clear roadmap to achieve it with minimal resistance. (ACINP, 2019) The main recommendations of the report centred around pieces that would allow for the prudent implementation of universal pharmacare by organizing prescription drug coverage in the same way universal health coverage is set up in Canada, and by capping out-of-pocket expenditures at $100 per household per year for drugs listed on a national formulary. (ACINP, 2019) As with Medicare, it would be up to individual provinces and territories to opt in to the universal pharmacare program by agreeing to national standards and funding parameters. The federal government would pay for the incremental costs to provinces and territories for expanding coverage and implementing pharmacare in their jurisdictions. Part of the national standards would be to reimburse all drugs listed on a national formulary, but provinces and

territories could decide to reimburse additional drugs if they want. More importantly, employers could also provide additional coverage if desired, which would make sure that the federal government would not be taking away current private coverage from any employee. This provision would hopefully placate an important talking point of groups opposed to universal pharmacare. (Gangcuangco, 2024; Gagnon, 2021) The phased implementation would proceed as follows:

- Creation of a Canadian Drug Agency: This agency would manage a national formulary of reimbursed drugs, negotiate confidential rebates, collect data on drug utilization, and provide prescribing guidelines.

- Phased Implementation: Starting in January 2022, the program would initially cover a basket of essential medicines,2 with a gradual extension of coverage through negotiations with manufacturers to ensure value-for-money. Comprehensive universal pharmacare would be fully realized by 2027.

- Coverage for Rare Diseases: Specific pathways for reimbursing drugs for rare diseases would be established by 2022.

The Hoskins Report proposed a gradual build-up, starting with foundational elements to prove the concept before expanding the program. This phased approach aimed to minimize disruption and allow stakeholders time to adjust. Following the report’s release, the Liberal government committed to implementing universal pharmacare and adopting the report’s recommendations. (Webster, 2019)

2.3 STEPS FORWARD, STEPS BACK

Progress towards implementing the Hoskins report recommendations was initially slow. In 2019, the federal budget allocated funds for creating a national drug agency. (Young, 2019) However, the COVID-19 pandemic in 2020 disrupted these efforts. The pandemic shifted the focus of federal-provincial relations, revealing the critical state of long-term care facilities and prompting the federal government to consider establishing national standards for this area of healthcare. (Estabrooks, et al., 2020) This focus led to push back from provinces and territories, who viewed increased federal involvement in healthcare as encroaching on their constitutional jurisdiction. (Gallant, 2020) Consequently, discussions about universal pharmacare stalled.

The only significant movement since the pandemic has been the 2021 agreement between PEI and the federal government, (Wilson, 2021) which saw the federal government commit to additional funding for PEI’s 29 existing public drug plans, (Health Canada, 2021) without implementing a universal pharmacare program in the province.

In 2022, a political shift signaled a potential renewal of pharmacare initiatives. The 2021 federal election resulted in a minority government for the Liberal Party, which entered a Confidence and Supply Agreement with the New Democratic Party of Canada (NDP) in March 2022. (Office of the Prime Minister of Canada, 2022) This agreement included a condition for advancing universal pharmacare based on the Hoskins Report’s recommendations. (Lexchin, 2022; Office of the Prime Minister of Canada 2022)

As a result, legislation to introduce the first phase of a national pharmacare program, Bill C-64, An Act respecting Pharmacare, was introduced in the House of Commons on February 29, 2024. (Health Canada, 2024a) The Confidence and Supply Agreement was officially ended on September 4, 2024, while Bill C-64 was already awaiting ratification at Canadian Senate, and was passed on October 10th. The end of the Agreement did not automatically trigger an election, but Bill-64’s passing did become threatened by this precarious Parliamentary situation.

3. Bill C-64: An Act Respecting Pharmacare

Bill C-64, while universal pharmacare in principle, only proposes to cover contraceptives and drugs for diabetes. The basket of covered drugs is much smaller than the basket of essential medicines recommended by the Hoskins Report, though it still creates the ability to implement the institutions necessary for a national pharmacare system and, as a first step, begins testing the overall concept. The bill is designed to allow the basket of reimbursed drugs to be expanded in the future. The federal Minister of Health would also have to negotiate with each province and territory to determine the details and conditions that would allow funding of the universal coverage for listed drugs, without any out-of-pocket payments from patients. The details of what would be included in the negotiations remain obscure but will become apparent as the legislation is implemented.

3.1 COVERAGE FOR CONTRACEPTIVES AND DIABETES PRODUCTS

The inclusion of contraceptives, such as oral birth control pills, intrauterine devices (IUDs), and implants, (Health Canada, 2024b) represents a progressive stance on maternal and women’s health. Both the Liberal Party under Justin Trudeau and the NDP under Jagmeet Singh have emphasized feminist values, aligning with this approach. Universal coverage of contraceptives can significantly benefit many Canadians by removing financial barriers and preserving patient confidentiality. An American study found that providing free access to contraceptives could reduce unplanned pregnancies by 32 percent. (Bailey, 2023) Patients accessing coverage through a private plan face concerns regarding these drugs and devices appearing in the plan’s reimbursement billing history, which may be viewable by others, such as their parents or partner; compromising the confidentiality necessary for some women to access these products. However, access through a universal plan negates this weakness, as the patient’s history would be viewable to them alone. A gap-filling approach would make this privacy advantage of universal coverage inaccessible to anyone with a private plan; universal access is therefore the best way to preserve patient confidentiality. (Albanese, 2024; Action Canada, 2022)

The choice to cover products for diabetes is also very important considering the significance of the socio-economic disparities that exist regarding access to these drugs. (Ladd, et al., 2022; Giruparajah, et al., 2022) A 2012 study estimated that first-dollar coverage for diabetes products could save over 700 lives annually in Ontario alone. (Booth, et al., 2012) Improved adherence to treatments would likely reduce hospitalizations and medical visits, resulting in significant savings for non-drug related healthcare expenditures. (Isaranuwatchai, et al., 2020)

3.2 A BILL DECEITFUL BY DESIGN?

When submitted on February 29, 2024, Bill C-64 An Act Respecting Pharmacare was clearly written in haste to respect the deadline imposed by the Confidence and Supply Agreement between the Liberals and the NDP in Parliament. The wording of the Bill, while building on the Hoskins Report and calling for universal pharmacare, remained equivocal, and its implementation without clarity on these equivocations could lead to potential challenges and unintended consequences.

Among potential challenges, agreements with provinces and territories will be necessary, and resistance from some provinces is likely. Additionally, commercial interests benefiting from the current inefficient and wasteful system continued to lobby against universal pharmacare and for Bill C-64 to keep the back door open for a “fill-the-gap” approach in which public coverage would be offered only to those without existing private coverage. (McLauchlan, 2024) More concerning, Health Minister Mark Holland has hinted that Bill C-64 would allow future federal-provincial agreements to be based on a fill-the-gap approach. (CPAC, 2024) Furthermore, the amount of funds allocated in the federal budget to implement national pharmacare also indicates that it may only cover existing gaps, without providing real universal coverage for Canadians. (Campbell, 2024)

While Bill C-64 seemed clear in supporting the implementation of a single-payer universal pharmacare model by beginning with the coverage of contraceptives and diabetes products, the wording of the Bill remains vague enough to allow for different interpretations. (Sanci, 2024; Morgan & Herder, 2024) This ambiguity in Bill C-64 raises the question: was the Bill designed to entrench a “fill-the-gap” approach in Canadian drug, while claiming to the contrary that it would implement universalized pharmacare? A bill of this design could be considered deceitful, placating the popular demand for universal pharmacare while purposely serving the interests of industry.

At issue with Bill C-64 is that pharmacare is defined as, “a program that provides coverage of prescription drugs and related products” (régime d’assurance-médicaments). However, pharmacare should be defined, instead, as a public program and not just any type of program that provides drug coverage. A second issue with Bill C-64 is that the word “universal” is used in an equivocal manner. A universal program should normally refer to the concept of universality, that has been well defined by social policy experts. (Béland, Marchildon, & Prince, 2019; Prince, 2014). According to the Canadian social policy textbook, Universality and Social Policy in Canada:

…in Universality as a distinctive governing instrument in social policy refers to public provisions in the form of benefits, services, or general rules anchored in legislation instead of discretionary public sector programming or provisions in the private sector, the domestic sector, or the voluntary sector, including charitable measures. Accessibility rests on citizenship or residency irrespective of financial need or income, and the benefit or service or rule is applicable to the general population (or a particular age group, such as children or older people) of a political jurisdiction. The operating principle for universal provision is of equal benefits or equal access. A further expression of this general sense of political community is that financing universal programs is wholly or primarily through general revenue sources. This points to the direct link between general taxation and universality because, in contrast to social insurance programs such as Employment Insurance and the Canada Pension Plan, which are typically financed through dedicated payroll contributions, universal programs depend on the flow of general fiscal revenues associated with income and sales taxes.

Béland, Marchildon & Prince, 2019, pp. 4

Universality as a program design feature means that a program then provides goods and services to all without criteria relating to individual or family income – it is not determined by a test of means or income. While people can sometimes opt-out or refuse the benefits of a universal program if this is their preference, a universal program is a public program offered to everyone, regardless of socioeconomic status. “Universal coverage” cannot mean that coverage is provided to everyone one way or the other; “universal” cannot describe a scheme where only some have access to public coverage and others must access a private option. For example, the Quebec pharmacare regime covers everyone in the province through a mix of private and public coverage; Quebec calls it a “general regime” (not a “universal regime”) because, if the regime were to provide coverage to all, it does not fit the definition of “universal” as used in social policy. The word “universal” does not appear anywhere in its “Loi sur l’assurance-médicaments,” (A-29.01) or in its “Règlement sur le Régime général d’assurance-médicaments.” (A-29.01, r.04) In contrast, the word “universal” appeared eleven times in Bill C-64. If Bill C-64 can be interpreted as the implementation of a drug coverage program like the scheme implemented in Quebec, then the word “universal” in Bill C-64 cannot describe the proposed program.

Instead, Bill C-64 as passed could open the door to the entrenchment of mandatory private coverage for everybody, which could enable a “universal pharmacare” considering that everyone would have access to a drug plan. This possibility is especially concerning, since the Parliamentary Budget Officer produced a report earlier in 2024 amid the Bill’s legislative processing that analyzed the cost of implementing C-64, indicating through its assumptions that private drug plans would continue to reimburse contraceptives and diabetes products covered by the public drug plan. (Barkova, 2024) Considering that it would be irrational for a private plan to reimburse something that could be reimbursed by another payer, one needs to assume that private plans could be compelled to maintain reimbursement of these products, for example by making them mandatory when available, as is the case in Quebec.

When questioned about the possibility for C-64 being used as a backdoor to entrench private coverage during Senate testimony regarding the Bill on September 18, 2024, Health Minister Holland refused to commit that the program would be publicly administered. (Senate of Canada, 2024) When asked, “Minister, will national pharmacare be publicly administered?” Minister Holland replied to the inquiry: “I’m ambivalent about that.” After receiving many criticisms about C-64 An Act of Respecting Pharmacare because it could maintain the current patchwork of drug coverage, and backdoor private administration, rather than the real implementation of universal pharmacare, Minister Holland wrote to the Senate on September 30, 2024 to clarify his position, and asserted that, “[u]nder this program, the cost of these medications will be paid for and administered through the public plan, rather than through a mix of public and private payers.” (Kirkup, 2024)

While the letter clarifies the Minister’s position about the government’s intended use of the Bill, it does not resolve the ambiguity found in the Bill itself. The door remains open for a deceitful use of the bill, for example, by the next federal health minister who may seek to implement a different version of national drug coverage that shifts away from it’s intended public administration.

4. Conclusion

The current patchwork of public and private drug plans creates high costs and does not provide good access to prescription drugs for Canadians. While Bill C-64 may be groundbreaking for public drug coverage in Canada, it is a very small step towards universal pharmacare as it only covers contraceptives and diabetes products. It could still very well be the small step that enables the institutional capacities necessary to create an efficient national drug coverage system that could replace, in the long run, the existing patchwork of tens of thousands of public and private drug plans.

At the time of writing in October 2024, it is still unclear if, in the end, anything was achieved by the reform of drug coverage in Canada. The ratification of Bill C-64 could end up being a game changer that transforms the landscape of drug coverage in Canada. Everything will depend in the ways in which the bill will be implemented and in the capacity of the Federal Government to achieve agreements with provinces for deploying the foundations of what could become the first steps of a real pharmacare system in Canada. However, because of the vague language of the bill and because of the unrelentless lobbying of commercial stakeholders, these first steps can very well end up even further entrenching the current inefficient, inequitable and wasteful mishmash of drug plans that has characterized Canadian drug coverage since the 1960s.

Notes

- The descriptions are based on information provided by CIHI (Canadian Institute for Health Information 2024) and the Patented Medicines Price Review Board (Patented Medicine Prices Review Board 2024), which are sources that can be consulted to obtain more details about public drug coverage in other provinces as well. ↩︎

- Essential medicines normally cover most of the health needs of a

population and they are also less expensive. (Taglione et al. 2017) ↩︎

References

Click to expand for full list of references

20Sense (2022) “A Balancing Act: How Private Payers Are Meeting the Needs of Specialty Medicine,” 20Sense report 20, Toronto: 20Sense. Available: https://www.20sense.ca/articles/20-02

ACINP (2019) “A Prescription for Canada: Achieving Pharmacare for All – Final Report of the Advisory Council on the Implementation of National Pharmacare,” Ottawa: Health Canada. Available: https://www.canada.ca/en/health-canada/corporate/about-health-canada/public-engagement/external-advisory-bodies/implementation-national-pharmacare/final-report.html.

Action Canada. (2022) “Policy Brief: Canada’s Pharmacare Plan Should Provide Access to All Forms of Contraception,” Action Canada. Available: https://www.actioncanadashr.org/sites/default/files/2022-11/Policy%20Brief%20Canada%E2%80%99s%20Pharmacare%20Plan%20Should%20Provide%20Access%20to%20All%20Forms%20of%20Contraception.pdf

Adams O & Smith J (March 2017) “National Pharmacare in Canada: 2019 or Bust?” The School of Public Policy Publications, 10. Available: https://doi.org/10.11575/sppp.v10i0.42619.

Albanese M (February 25, 2024) “Why Access to Free Prescription Contraception Is a Crucial Component of a National Pharmacare Program for Canada,” The Conversation. Available: http://theconversation.com/why-access-to-free-prescription-contraception-is-a-crucial-component-of-a-national-pharmacare-program-for-canada-224040

Bailey M (2023) “Increasing Financial Access to Contraception for Low-Income Americans,” The Hamilton Project, Washington: Brookings Institution. Available: https://www.brookings.edu/articles/increasing-financial-access-to-contraception-for-low-income-americans/

Barkova L (2024) “An Act Respecting Pharmacare.” Office of the Parliamentary Budget Officer, Legislative Costing Note, Ottawa. Available: https://www.pbo-dpb.ca/en/publications/LEG-2425-003-S–an-act-respecting-pharmacare–loi-concernant-assurance-medicaments

Barkova L & Malanik-Busby C (2023) “Cost Estimate of a Single-Payer Universal Drug Plan” Office of the Parliamentary Budget Officer, Ottawa. Available: https://www.pbo-dpb.ca/en/publications/RP-2324-016-S–cost-estimate-single-payer-universal-drug-plan–estimation-couts-un-regime-assurance-medicaments-universel-payeur-unique.

Barnes S (2015) Low Earnings, Unfilled Prescriptions: Employer-Provided Health Benefit Coverage in Canada, Toronto, Ontario: Wellesley Institute.

Béland D, Marchildon G & Prince M J (2019) “Universality and Social Policy in Canada,” Johnson-Shoyama Series on Public Policy, Toronto: University of Toronto Press.

Blatchford A (March 2, 2018) “Critics Call for Morneau’s Ouster from Pharmacare File over Remarks about Stud,” Canada’s National Observer. Available: https://www.nationalobserver.com/2018/03/02/news/critics-call-morneaus-ouster-pharmacare-file-over-remarks-about-study

Bolatova T & Law M R (2019) “Income-Related Disparities in Private Prescription Drug Coverage in Canada,” Canadian Medical Association Open Access Journal, 7(4), pp. E618-23. Available: https://doi.org/10.9778/cmajo.20190085

Boothe K (2018) “Ideas and the Pace of Change: National Pharmaceutical Insurance in Canada, Australia, and the United Kingdom,” Studies in Comparative Political Economy and Public Policy, Toronto: University of Toronto Press. Available: https://doi.org/10.3138/9781442617377

Brandt J, Shearer B & Morgan S G (2018) “Prescription Drug Coverage in Canada: A Review of the Economic, Policy and Political Considerations for Universal Pharmacare,” Journal of Pharmaceutical Policy and Practice, 11(1), pp. 28. Available: https://doi.org/10.1186/s40545-018-0154-x

Campbell D J T, Manns B J, Soril L J J & Clement F (2017) “Comparison of Canadian Public Medication Insurance Plans and the Impact on Out-of-Pocket Costs,” Canadian Medical Association Open Access Journal, 5(4), pp. 808–813. Available: https://doi.org/10.9778/cmajo.20170065

Campbell I (April 25, 2024) “Budget’s ‘Slow Rollout’ Pharmacare Funding Leaves Program Vulnerable to Change in Governments, Say Policy Experts,” The Hill Times. Available: https://www.hilltimes.com/story/2024/04/25/budgets-slow-rollout-pharmacare-funding-leaves-program-vulnerable-to-change-in-governments-say-policy-experts/419919/

Canada Royal Commission on Health Services (1964) Royal Commission on Health Services. Ottawa: Royal Duhamel, Queen’s Printer and Controller of Stationery.

Canadian Institute for Health Information (2023) “National Health Expenditure Trends.” CIHI. Available: https://www.cihi.ca/en/national-health-expenditure-trends

— (2024) “Pharmaceutical Data Tool.” CIHI. Available: https://www.cihi.ca/en/pharmaceutical-data-tool

Casey B (2018) “Pharmacare Now: Prescription Medicine Coverage for All Canadians,” Ottawa: Standing Committee on Health, House of Commons, Canada. Available: https://www.ourcommons.ca/content/committee/421/hesa/reports/rp9762464/hesarp14/hesarp14-e.pdf

Charbonneau M & Gagnon M-A (2018) “Surviving Niche Busters: Main Strategies Employed by Canadian Private Insurers Facing the Arrival of High Cost Specialty Drugs,” Health Policy (Amsterdam, Netherlands), 122(12), pp. 1295–1301. Available: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.healthpol.2018.08.006

Commission on the Future of Health Care in Canada (2002) Building on Values: The Future of Health Care in Canada, Documents Collection, Saskatoon: Commission on the Future of Health Care in Canada.

Cortes K & Smith L (2022) “Pharmaceutical Access and Use during the Pandemic,” 75006–X, Insights on Canadian Society, Ottawa: Statistics Canada. Available: https://www150.statcan.gc.ca/n1/pub/75-006-x/2022001/article/00011-eng.htm

Cable Public Affairs Channel (dir. 2024) Ministers on Housing for Ont. Newcomers, Pharmacare Plan. Available: https://www.cpac.ca/scrums/episode/ministers-on-housing-for-ont-newcomers-pharmacare-plan–june-4-2024?id=506e6d71-c9f6-4072-8711-3c1397634129

Daw J R & Morgan S G (2012) “Stitching the Gaps in the Canadian Public Drug Coverage Patchwork? A Review of Provincial Pharmacare Policy Changes from 2000 to 2010,” Health Policy (Amsterdam, Netherlands), 104 (1), pp. 19–26. Available: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.healthpol.2011.08.015

Demers V, Melo M, Jackevicius C, Cox J, Kalavrouziotis D, Rinfret S, Humphries K H, Johansen H, Tu J V & Pilote L (2008) “Comparison of Provincial Prescription Drug Plans and the Impact on Patients’ Annual Drug Expenditures,” Canadian Medical Association Journal, 178(4), pp. 405–409. Available: https://doi.org/10.1503/cmaj.070587.

Estabrooks C A, Straus S E, Flood M F, Keefe J, Armstrong P, Donner G J, Boscart V, Ducharme F, Silvius J L & Wolfson M C (2020) “Restoring Trust: COVID-19 and the Future of Long-Term Care in Canada,” Facets (Ottawa), 5(1), pp. 651–691. Available: https://doi.org/10.1139/facets-2020-0056

Federal Trade Commission, United States (2024) “Pharmacy Benefit Managers: The Powerful Middlemen Inflating Drug Costs and Squeezing Main Street Pharmacies,” Interim Staff Report, Washington: Federal Trade Commission. Available: https://www.ftc.gov/reports/pharmacy-benefit-managers-report

Fierlbeck K (2011) Health Care in Canada: A Citizen’s Guide to Policy and Politics, Toronto: University of Toronto Press.

Fierlbeck K (2011) Health Care in Canada: A Citizen’s Guide to Policy and Politics, Toronto: University of Toronto Press.

Fierlbeck K & Marchildon G P (2023) The Boundaries of Medicare: Public Health Care beyond the Canada Health Act, McGill-Queen’s/Associated Medical Services Studies in the History of Medicine, Health, and Society 61. Montreal; Kingston ; London ; Chicago: McGill-Queen’s University Press.

Flood C M, Thomas B & Moten A A (2018) Universal Pharmacare and Federalism: Policy Options for Canada, Vol. 68, IRPP Study, Montreal: Institute for Research on Public Policy. Available: https://irpp.org/research-studies/universal-pharmacare-and-federalism-policy-options-for-canada/

Forrest M (March 1, 2018) “Morneau Prefers a Public-Private Pharmacare Plan, but Government Health Committee May Disagree,” National Post. Available: https://nationalpost.com/news/politics/morneau-prefers-a-public-private-pharmacare-plan-but-government-health-committee-may-disagree

Gagnon M-A (2012) “Pharmacare and Federal Drug Expenditures: A Prescription for Change,” in How Ottawa Spends, 2012-2013, pp. 161–172, Montreal: MQUP. Available: https://doi.org/10.1515/9780773587786-010

Gagnon M-A (2014) A Roadmap to a Rational Pharmacare Policy in Canada, Ottawa: Canadian Federation of Nurses Unions. Available: https://nursesunions.ca/wp-content/uploads/2017/05/Pharmacare_FINAL.pdf

Gagnon M-A (2017) “The Role and Impact of Cost-Sharing Mechanisms for Prescription Drug Coverage,” Canadian Medical Association Journal, 189(19), pp. 680–681. Available: https://doi.org/10.1503/cmaj.170169

Gagnon M-A (2021) “Understanding the Battle for Universal Pharmacare in Canada Comment on ‘Universal Pharmacare in Canada,’” International Journal of Health Policy and Management, 10(3)pp. 168–171. Available: https://doi.org/10.34172/ijhpm.2020.40

Gagnon M-A & Hébert G (2010) “The Economic Case for Universal Pharmacare: Costs and Benefits of Publicly Funded Drug Coverage for All Canadians,” Canadian Centre for Policy Alternatives. Available: https://policyalternatives.ca/publications/reports/economic-case-universal-pharmacare

Gagnon M-A, Vadeboncoeur A, Charbonneau M & Morgan S (2017) Le régime public-privé d’assurance médicaments du Québec: Un modèle obsolète ? Documents collection, Montreal: Institut de recherche et d’informations socio-économiques.

Gallant J (December 8, 2020) “Provinces on a Collision Course with Ottawa over National Standards for Long-Term Care,” Toronto Star. Available: https://www.thestar.com/politics/federal/provinces-on-a-collision-course-with-ottawa-over-national-standards-for-long-term-care/article_63e8ac90-2b53-58a3-b8ee-eb4b2de35002.html

Gangcuangco T (March 1, 2024) “CLHIA: Government’s Pharmacare Plan Set to Be ‘More Burdensome,’” Insurance Business. Available: https://www.insurancebusinessmag.com/ca/news/life-insurance/clhia-governments-pharmacare-plan-set-to-be-more-burdensome-479479.aspx

Giruparajah M, Everett K, Shah B R, Austin P C, Fuchs S, & Shulman R (2022) “Introduction of Publicly Funded Pharmacare and Socioeconomic Disparities in Glycemic Management in Children and Youth with Type 1 Diabetes in Ontario, Canada: A Population-Based Trend Analysis,” Canadian Medical Association Journal, 10(2), pp. 519–526. Available: https://doi.org/10.9778/cmajo.20210214

Goldsmith L J, Kolhatkar A, Popowich D, Holbrook A M, Morgan S G & Law M R (December 2017) “Understanding the Patient Experience of Cost-Related Non-Adherence to Prescription Medications through Typology Development and Application,” Social Science & Medicine (1982), 194, pp. 51–59. Available: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.socscimed.2017.10.007

Health Canada (August 11, 2021) “Government of Canada and Prince Edward Island Accelerate Work to Implement Pharmacare,” News releases, Government of Canada. Available: https://www.canada.ca/en/health-canada/news/2021/08/government-of-canada-and-prince-edward-island-accelerate-work-to-implement-pharmacare.html

— (February 29, 2024) “Government of Canada Introduces Legislation for First Phase of National Universal Pharmacare,” News releases, Government of Canada. Available: https://www.canada.ca/en/health-canada/news/2024/02/government-of-canada-introduces-legislation-for-first-phase-of-national-universal-pharmacar.html

(February 29, 2024) “Universal Access to Contraception,” Backgrounders, Government of Canada. Available: https://www.canada.ca/en/health-canada/news/2024/02/backgrounder-universal-access-to-contraception.html

Hennessy D, Sanmartin C, Ronksley P, Weaver R, Campbell D, Manns B, Tonelli M & Hemmelgarn B (June 2016) “Out-of-Pocket Spending on Drugs and Pharmaceutical Products and Cost-Related Prescription Non-Adherence among Canadians with Chronic Disease,” Health Reports, 27, pp. 3–8.

Himmelstein D U, Campbell T & Woolhandler S (2020) “Health Care Administrative Costs in the United States and Canada, 2017,” Annals of Internal Medicine, 172(2), pp. 134–142. Available: https://doi.org/10.7326/M19-2818

Innovation, Science and Economic Development Canada (2024) “Pharmaceutical Industry Profile,” Government of Canada, Innovation, Science and Economic Development Canada. Available: https://ised-isde.canada.ca/site/canadian-life-science-industries/en/biopharmaceuticals-and-pharmaceuticals/pharmaceutical-industry-profile

Isaranuwatchai W, Fazli G S, Bierman A S, Lipscombe L L, Mitsakakis N, Shah B R, Wu C F, Johns A & Booth G L (2020) “Universal Drug Coverage and Socioeconomic Disparities in Health Care Costs Among Persons With Diabetes,” Diabetes Care, 43(9), pp. 2098–2105. Available: https://doi.org/10.2337/dc19-1536

Kirkup K (September 30, 2024) “Pharmacare Bill Would See Medications Paid for, Administered through Public Plan, Holland Writes in Letter,” The Globe and Mail. Available: https://www.theglobeandmail.com/politics/article-pharmacare-bill-would-see-medications-paid-for-administered-through/

Ladd J M, Sharma A, Rahme E, Kroeker K, Dubé M, Simard M, Plante C, et al. (2022) “Comparison of Socioeconomic Disparities in Pump Uptake Among Children With Type 1 Diabetes in 2 Canadian Provinces With Different Payment Models,” JAMA Network Open, 5(5), pp. e2210464. Available: https://doi.org/10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2022.10464

Law M R, Kratzer J & Dhalla I A (2014) “The Increasing Inefficiency of Private Health Insurance in Canada,” Canadian Medical Association Journal, 186(12), pp. 470–474. Available: https://doi.org/10.1503/cmaj.130913

Lexchin J (2022) “After More Than 50 Years, Pharmacare (and Dental Care) Are Coming to Canada,” International Journal of Health Services, 52(3), pp. 341–346. Available: https://doi.org/10.1177/00207314221100654

Lopert R, Docteur E & Morgan S (2018) Body Count: The Human Cost of Financial Barriers to Prescription Medications, Ottawa: Canadian Federation of Nurses Unions.

Malanik-Busby C, Jacques J, Mahabir M & Wodrich N (2017) “Federal Cost of a National Pharmacare Program,” Office of the Parliamentary Budget Officer, Ottawa. Available: https://www.pbo-dpb.ca/en/publications/RP-1718-349–federal-cost-of-a-national-pharmacare–couts-pour-le-gouvernement-federal-dun

Marchildon G (2021) Health Systems in Transition: Canada, 3rd Edition, Toronto: University of Toronto Press. Available: https://doi.org/10.3138/9781487537517

McLauchlan M (July 8, 2024) “Pro-Pharma Lobbying Picks up as Pharmacare Bill Nears Final Approval,” Investigative Journalism Foundation. Available: https://theijf.org/pro-pharma-lobbying-picks-up-as-pharmacare-bill-nears-final-approval

Men F, Gundersen C, Urquia M L & Tarasuk V (2019) “Prescription Medication Non-adherence Associated with Food Insecurity: A Population-Based Cross-Sectional Study,” Canadian Medical Association Journal, 7(3), pp. 590–597. Available: https://doi.org/10.9778/cmajo.20190075

Miregwa B N, Holbrook A, Law M R, Lavis J N, Thabane N, Dolovich L & Wilson M G (2022) “The Impact of OHIP+ Pharmacare on Use and Costs of Public Drug Plans among Children and Youth in Ontario: A Time-Series Analysis,” Canadian Medical Association Journal, 10(3), pp. 848–855. Available: https://doi.org/10.9778/cmajo.20210295

Morgan M G, Gagnon M-A, Charbonneau M & Vadeboncoeur A (2017) “Evaluating the Effects of Quebec’s Private–Public Drug Insurance System,” Canadian Medical Association Journal, 189(40), pp. 1259–1263. Available: https://doi.org/10.1503/cmaj.170726

Morgan S G, Gagnon M-A, Mintzes B & Lexchin J (2016) “A Better Prescription: Advice for a National Strategy on Pharmaceutical Policy in Canada,” Healthcare Policy, 12(1), pp. 18–36.

Morgan S G & Herder M (2024) “Pharmacare Act Does Not Prescribe Universal, Public Pharmacare,” Canadian Medical Association Journal, 196(27), pp. 942–943. Available: https://doi.org/10.1503/cmaj.240935

Morgan S G, Law M, Daw J R, Abraham L & Martin D (2015) “Estimated Cost of Universal Public Coverage of Prescription Drugs in Canada,” Canadian Medical Association Journal, 187(7), pp. 491–497. Available: https://doi.org/10.1503/cmaj.141564

Morgan S G, Vogler S & Wagner A K (2017) “Payers’ Experiences with Confidential Pharmaceutical Price Discounts: A Survey of Public and Statutory Health Systems in North America, Europe, and Australasia,” Health Policy, 121(4), pp. 354–362. Available: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.healthpol.2017.02.002

National Forum on Health (1997) Canada Health Action: Building on the Legacy, Ottawa: National Forum on Health.

O’Brady S, Gagnon M-A & Cassels A (2015) “Reforming Private Drug Coverage in Canada: Inefficient Drug Benefit Design and the Barriers to Change in Unionized Settings,” Health Policy (Amsterdam, Netherlands), 119(2), pp. 224–231. Available: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.healthpol.2014.11.013

Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (2023) “Health at a Glance 2023; OECD Indicators,” Paris. Available: https://www.oecd.org/en/publications/2023/11/health-at-a-glance-2023_e04f8239.html

Office of the Prime Minister of Canada (March 22, 2022) “Delivering for Canadians Now,” News release, Ottawa. https://www.pm.gc.ca/en/news/newsreleases/2022/03/22/delivering-canadians-now

Patel M R, Piette J D, Resnicow K, Kowalski-Dobson T & Heisler M (2016) “Social Determinants of Health, Cost-Related Non-Adherence, and Cost-Reducing Behaviors among Adults with Diabetes: Findings from the National Health Interview Survey,” Medical Care, 54(8), pp. 796–803. Available: https://doi.org/10.1097/MLR.0000000000000565

Patented Medicine Prices Review Board (January 30, 2024) “Public Drug Plan Designs,” Government of Canada. Available: https://www.canada.ca/en/patented-medicine-prices-review/services/npduis/analytical-studies/supporting-information/public-drug-plan-designs.html

Patented Medicines Price Review Board (2024) “Annual Report 2022,” Ottawa: Patented Medicines Price Review Board. Available: https://www.canada.ca/en/patented-medicine-prices-review/services/annual-reports/annual-report-2022.html

Persaud N, Bedard M, Boozary A, Glazier R H, Gomes T, Hwang S W, Jüni P, et al. (2023) “Effect of Free Medicine Distribution on Health Care Costs in Canada Over 3 Years: A Secondary Analysis of the CLEAN Meds Randomized Clinical Trial,” JA-MA Health Forum, 4(5) pp. e231127. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamahealthforum.2023.1127

Pharmacare 2020 (May 3, 2022) “Open Letter from Experts in Support of Universal Pharmacare.” Available: https://pharmacare2020.ca/our-letter

Prince M J (2014) “The Universal in the Social: Universalism, Universality, and Universalization in Canadian Political Culture and Public Policy,” Canadian Public Administration, 57(3) pp. 344–361. Available: https://doi.org/10.1111/capa.12075

Régie de l’Assurance-Maladie du Québec (2023) “Rapport annuel de gestion 2022-2023,” Annual Report, Quebec: RAMQ. Available: https://www.ramq.gouv.qc.ca/fr/media/15411

Régie de l’Assurance-Maladie du Québec (July 1, 2024.) “Tarifs en vigueur,” Quebec: RAMQ. Available. https://www.ramq.gouv.qc.ca/fr/citoyens/assurance-medicaments/tarifs-vigueur

Robbins R & Abelson R (June 21, 2024) “The Opaque Industry Secretly Inflating Prices for Prescription Drugs,” The New York Times, sec. Business. Available: https://www.nytimes.com/2024/06/21/business/prescription-drug-costs-pbm.html

Sanci T (June 8, 2024) “Pharmacare Bill and Liberal Messaging at Odds, Confusing Stakeholders on Vision for ‘Single-Payer’ System,” The Hill Times. Available: https://www.hilltimes.com/story/2024/06/08/pharmacare-bill-and-liberal-messaging-at-odds-confusing-stakeholders-on-vision-for-single-payer-system/424836

Senate of Canada (September 18, 2024) “Transcript of Standing Senate Committee on Social Affairs, Science and Technology (37th Parliament, 2nd Session).” Standing Senate Committee on Social Affairs. Available: https://sencanada.ca/en/committees/soci/

Statistics Canada (June 19, 2024) “Population Estimates, Quarterly,” Table 17-10-0009-01., Government of Canada. Available: https://www150.statcan.gc.ca/t1/tbl1/en/tv.action?pid=1710000901

SunLife (April 13, 2023.) “Product Listing Agreements (PLAs): Managing Drug Costs within Your Benefits Plan.” Available: https://www.sunlife.ca/workplace/en/group-benefits/workplace-health-resources/sponsor-latest-news/over-50-employees/product-listing-agreements-managing-drug-costs-within-your-benefits-plan/

Webster P (2019) “Trudeau Signals Support for Canadian Pharmacare,” The Lancet, 393(10190), pp. 2482. Available: https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(19)31469-2

Wilson J (August 21, 2021) “Feds Sign First Agreement towards National Pharmacare,” Canadian HR Reporter. Available: https://www.hrreporter.com/focus-areas/compensation-and-benefits/feds-sign-first-agreement-towards-national-pharmacare/358857

Young L (March 19, 2019) “No Pharmacare in Federal Budget, but Funding for a National Drug Agency,” Global News. Available: https://globalnews.ca/news/5073058/canada-pharmacare-budget-2019/