Part memoir, part history, part political manifesto, Seeking Social Democracy offers the first full-length treatment of Ed Broadbent’s ideas and remarkable seven decade engagement in public life.

In dialogue with three collaborators from different generations, Ed Broadbent leads readers through a life spent fighting for equality in Parliament and beyond: exploring the formation of his social democratic ideals, his engagement on the international stage, and his relationships with historical figures from Pierre Trudeau and Fidel Castro to Tommy Douglas, René Lévesque, and Willy Brandt.

Excerpted and adapted from Seeking Social Democracy by Ed Broadbent with Frances Abele, Jonathan Sas & Luke Savage. © 2023 by Ed Broadbent, Frances Abele, Jonathan Sas & Luke Savage. All rights reserved. Published by ECW Press Ltd. www.ecwpress.com

Listen to our interview with Ed Broadbent on Perspectives Journal Podcast discussing Seeking Social Democracy.

Join the Broadbent Institute in Toronto on October 22nd for a book launch event at Toronto Reference Library with Ed Broadbent and co-authors Frances Abele, Jonathan Sas, and Luke Savage. Reserve your seat now!

Social Democracy without Borders

Jonathan Sas: Your vice presidency at the Socialist International coincided with your leadership of the NDP, but is far less well-known or well-documented than other parts of your political career. How would you broadly characterize the SI and its work during the period in which you were involved?

Ed Broadbent: The work of the organization during that time was in a very important sense the extension of European social democracy in its golden age. The figures I met through the Socialist International were not just people with whom I shared common ground. They were people who represented the movement at its apogee and who had — alongside their immediate predecessors — laid the foundations for the modern welfare state and the practical realization of economic and social rights. During the postwar decades, this project represented the main challenge to the capitalist order as it was then constituted in many Western countries.

Many of the European leaders involved in the Socialist International had lived through the economic turmoil of the 1930s and had seen first-hand the kinds of outcomes that unbound markets guaranteed: both for ordinary people and for liberal institutions that had been ill-equipped to beat back the fascist threat. The solution, for them, was to confront the market mechanism and carve out a broad set of social and economic rights: to healthcare, education, pensions, housing, decent employment, and other social goods.

This was the struggle that had defined the left for at least two generations of politicians in labour, socialist, and social democratic parties in the decades after the Second World War. And it’s important to remember that it was not only a challenge to the existing liberal order in North America and Europe, it was also an explicit rejection of the kind of centralized and bureaucratized state socialism that had been established in Eastern Europe (and in many cases directly imposed by the Red Army). That was the wider context for the work of the Socialist International while Brandt was president, and also very much the impetus for his wider mission to offer a constructive global alternative to both the American and Soviet models.

As for the activities of the organization itself, they were a mixture of debate, discussion, and direct material support that would be offered in various countries. Even as early as the mid- 1970s, the formal and plenary sessions were already becoming like bureaucratized UN meetings in that leaders would make speeches that had already been typed up and sent out as press releases in their home countries. But on the final day of a conference, there would be leaders’ meetings that I found particularly useful in my capacity as a social democratic politician: these meetings typically had an open agenda, meaning they tended to feature free and no-holds-barred discussions or debates. There would be frank sharing of information about how different parties were responding to conditions in their own countries. There would be detailed discussions about income policy, taxation, labour rights, electoral strategy, and a whole range of issues, generally giving a broad sense of what seemed to be working or not working.

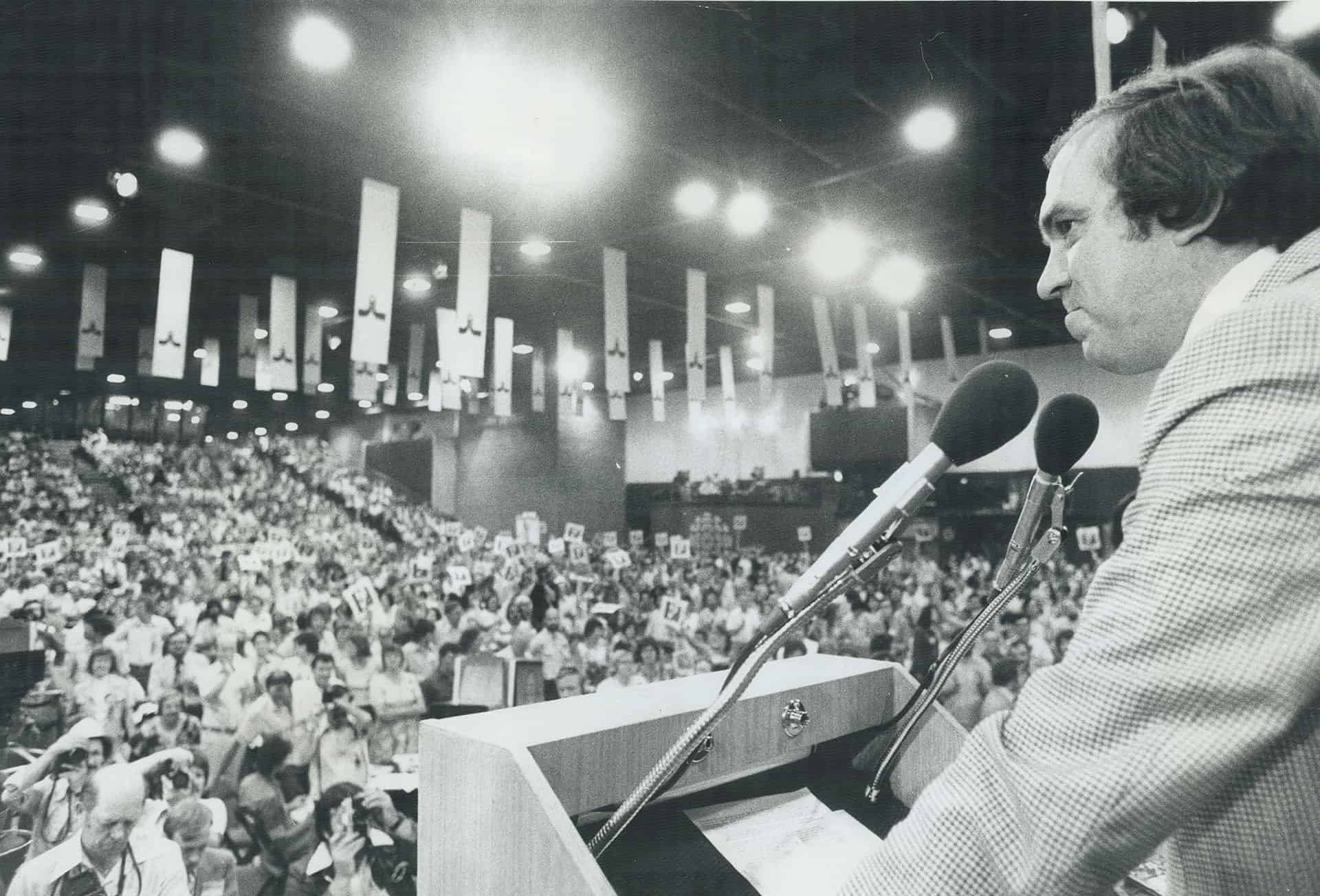

All of that was quite useful on its own terms, but it was ultimately in service of Brandt’s overriding strategic goal of promoting social democracy or democratic socialism as an attractive alternative to the rival models championed by the two Cold War superpowers. That necessitated expanding the Socialist International beyond its traditionally European scope. To that end, Brandt scheduled gatherings further afield: memorably in Japan, where he actually reached out to two competitors (the similarly named Democratic Socialist and Socialist parties) and asked them to host, in Vancouver in 1978, and Lima in 1986.

Vancouver, incidentally, is where I first properly met Brandt. The NDP acted as the host for the Socialist International Congress that year, and it was the first time the organization had ever met outside Europe.* Working with Willy as the hosting chair, I had to navigate for the first time the intricate dealings of a big international conference. This proved especially interesting because that conference was also where the Sandinistas made their debut on the world stage. Armed with revolutionary rhetoric, their large delegation scared the bejesus out of the good citizens of British Columbia and some of my NDP colleagues. The Sandinistas had recently overthrown the authoritarian government of Nicaragua. They consisted of progressive priests, social democrats, Leninists, and a host of other political tendencies. At this point in history, they acted cohesively to depose a tyrannical regime. Later on, their conflicting tendencies from within would lead to significant policy conflicts and ultimately to another authoritarian regime.

* The Vancouver Congress had a major focus on several areas: disarmament; redeploying military spending to development support for the Global South; and with Willy’s leadership, debate over how the conflict between East and West implicated divisions between North and South.

Central America became an important area of focus for the SI under Brandt’s leadership — among other things because it was such a significant front in the battle between U.S.-style capitalism and authoritarian statism. Our work there often brought us into direct conflict with the Americans, who were supporting some truly vicious regimes in places like Guatemala and El Salvador. The SI got the leaders of social democratic parties and movements throughout the region involved in its meetings, but it also in some cases offered them direct financial assistance. In the short-term, the goal was usually to call worldwide attention to the horrendous human rights abuses going on in these heavily militarized countries. But we also tried to foster a vibrant civil society and the kind of constitutional development and growth of representative democracy that would protect basic civil and political rights — while opening the door to the economic and social kind in the future.

All of it was very much an uphill battle. Because of their social democratic agenda, leaders like Guillermo Ungo in El Salvador were attacked as foreigners in their own countries. The danger some of our partners faced could also be even more serious than that. A friend from El Salvador, for example, travelled to Guatemala one weekend and never returned. They found his Volkswagen near the border, and he was almost certainly murdered by the ruling right-wing junta there. I met some truly courageous people in the course of that work, many of whom were quite literally risking their lives by getting involved with democratic movements.

Frances Abele: A major site of the superpower competition you’ve been talking about was Cuba, which experienced a popular revolution during the 1950s and then a failed invasion the following decade that was organized and financed by the United States. How did it figure in your work at SI and elsewhere? Where do you see its place in the broader geopolitical context we’re describing?

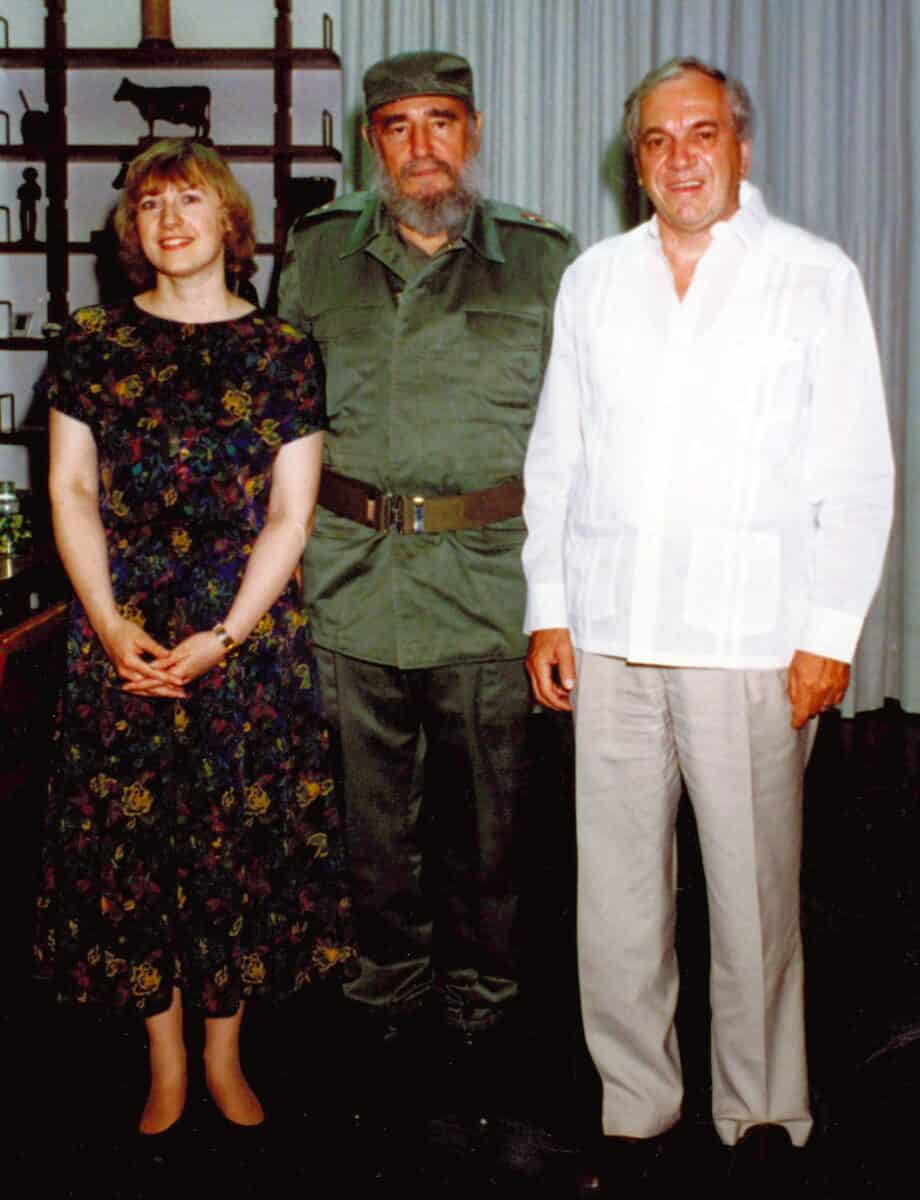

Broadbent: Cuba certainly stands out as an interesting case, and it was distinct from other communist administrations (like those in Eastern Europe) because its government was the product of an indigenous revolution rather than a phoney one imposed from outside. I supported Castro while a student and was pleased to see Batista overthrown. I, like so many others around the world, was optimistic and thought that he would bring democracy to Cuba. In various capacities — as an MP, as a vice president at SI, and later as head of Rights and Democracy — I ultimately had three encounters with him and got a chance to see what he was like up close.

The meetings were all a number of hours long and covered a tremendous swathe of ground. During the first two, I made a point of not discussing domestic politics in Cuba or raising questions about what was going on internally. At the time, what interested me was Castro’s analysis of Central America and the extent to which he and his movement were involved there. One thing I’d say about the meetings is that I never subsequently learned he had lied or misled me on anything, which mattered because I was trying to obtain an accurate picture of what was actually going on in Nicaragua, Guatemala, and other countries in the region. Much of what he had to say simply reinforced what I already knew, but in retrospect, I think those meetings were fairly constructive and went smoothly. He was the head of a communist party and government, whereas I was a social democrat, and we never discussed what significance those allegiances might have to our relationship. It just never came up.

The third meeting, which was in 1991, went very differently. By that time, the Soviet Union — which had been a major ally and source of material aid for Cuba — was disintegrating, and Castro was well aware of what that meant for Cuba, that is, the disappearance of subsidies upon which the economy depended. For some members of the Socialist International, this created an opportunity to move Cuba in a more democratic direction. The Spanish social democrat Felipe González had scheduled a meeting in Madrid for the following year to celebrate Columbus’s so-called “discovery” of America. The idea was that Castro could attend the meeting and announce certain democratic reforms, including free elections. In return, certain social democratic governments would provide financial assistance that would compensate for the economic damage done by the American embargo.

I put forward this proposal to Castro. I raised the question of financial assistance quite specifically with him because the Americans had importantly not been invited to Madrid: it would be Latin American governments only, and he had said in both public and private that he wasn’t going to yield to Yankee pressure to have multiparty democracy. I also tried, as forcefully as I could, to make a multipronged case that accepting the offer would ultimately be in his own long-term self-interest. First, I argued that (outsider as I was) my strong hunch was that if elections were held at that time, he would probably win. I also made the case that the Cuban revolution, which he very much symbolized, had been genuine as compared to what had until then prevailed in Eastern Europe — and that, by extension, a major reason the various Soviet satellite states were breaking up was that they had never been genuine revolutionary societies. For that reason, I argued, he should probably hold an election sooner rather than later if he and his successors wanted to avoid the same fate.

The argument didn’t go over well. In fact he rejected it outright. The conversation (which went on for at least three hours) had been on thin ice already because I had raised the case of a Cuban social democrat named Elizardo Sánchez who publicly supported the government’s social programs but wanted it to hold free elections. I had heard that the local Defence of the Revolution committee was terrorizing the residents where Sánchez’s mother lived: making noise twenty-four hours a day by beating pots and pans around the house. I had hoped Castro would intervene to stop the harassment. When I raised the issue, he just said “Sánchez is a worm and we are not going to be making any concessions” (or something to that effect). The meeting was a failure and I never saw him again. It was the one and only time our relationship had gotten acrimonious. But it was also the one and only time we had broached the subject of domestic politics and the question of democracy in Cuba.

Sas: He was a famously charismatic figure, and was known for great command of history, politics, and many other fields. What was he actually like when you were dealing with him in person? And what was your overall impression of him?

Broadbent: I think that he was, at heart, an authoritarian figure. He was interested in providing universal healthcare and education — which they did to a very high standard for a developing country — but he had no interest in promoting free discussion, freedom of association, or anything that might lead to the government being challenged. That attitude, which isn’t one I respect, revealed itself in parts of our conversations where he positioned himself as an authority on absolutely everything. He certainly was an autodidact and had a remarkable level of knowledge about a wide variety of subjects. On one occasion he sent me back to Canada with a giant bundle of medications to treat a medical condition I had (and, I would add, with some particularly fine cigars).

There was a certain generosity of spirit on his part that came through in an encounter like that. But it also showed his irrepressible desire to become master of every topic. I heard from others that, no matter what department of the government he was dealing with, he always had to be the dominant figure in policy discussions. To me, there’s an intellectual arrogance implicit in that behaviour and in his cruelty in the Sánchez case. Someone who did not support him was too readily considered contemptible.

Luke Savage: I suppose the common rejoinder around Cuba and the absence of free elections would be that Castro was concerned they would make the country more vulnerable to the efforts directed at it from within the United States. Because, in addition to the embargo, there were numerous assassination attempts on Castro and the U.S.-backed invasion of Cuba at the Bay of Pigs. He was presumably also thinking about what had happened in places like Chile, where the Allende government was overthrown in a violent coup. Given all of that, do you think Castro had a leg to stand on in rejecting the offer along with multiparty elections? To what extent do you think the repressive climates that took root in twentieth-century communist countries were endemic to, or the result of, outside pressure being applied by capitalist powers?

Broadbent: It’s a complex question, and one I think I would rather entrust to historians as opposed to political scientists. The answer is also going to be somewhat dependent on the country being discussed. If we’re talking about the USSR, I simply don’t know enough to offer a definitive answer about the extent to which the repressive direction of travel from the 1920s onward was endemic to communist institutions and practice, as opposed to being a response to pressure and interference from Western capitalist powers. Some of it clearly was, but I can’t offer much of an opinion as to exactly how much. What I can contribute is my own bias that the Bolshevik leadership, up to and including Lenin himself, had a marked authoritarian propensity. Given that, I think a lot of what occurred had to do with the ruling order within the USSR itself, and not just the hostile response elicited by the Russian Revolution.

When it comes to the Americas, which were the part of the world where I was most involved through the Socialist International, my judgement is more categorical. There, I would argue that American foreign policy has been repressive, particularly during the 1980s when Ronald Reagan was president. There was a marked ideological aggression coming from conservative parties across the West in those days, and in Central America, it manifested itself in a total intolerance toward even the most mildly progressive initiatives coming from democratic forces. Once there was a hint of anything like that, the logic of the Monroe Doctrine immediately kicked in — the imperative to protect American commercial interests in the former colonies to the south. And, as we saw in Reagan’s funding of the Contras, those guiding American foreign policy were willing to go against their own laws in order to pursue their right-wing crusade. That was ideologically driven at the highest level, and I don’t think it reflected any genuine pressure coming from the American people at all.

Turning back to Cuba, I think that the question is a some-what complicated one to answer. Castro had every reason to be suspicious after the Bay of Pigs invasion, which of course the Americans had organized and which was a flop. There is today a big state security apparatus in Cuba designed specifically to keep the Americans and the CIA out. Still, as I had tried to persuade Castro, there was good reason to believe his project could survive if he went ahead with the institutions necessary for multiparty elections. For one thing, nearby countries like Costa Rica had managed a degree of pluralist social democracy and, in that particular case, had actually done so without even having a military. Its former president, Óscar Arias, won a Nobel Peace Prize for his efforts to make peace in Central America.

I came to think that much of Castro’s talk about the Americans was self-serving and based on the domestic utility of the argument. Because Cubans remember the Bay of Pigs, the direction Castro took afterwards would be forever justified by him as a necessary defence against an external threat. When I was first elected to Parliament, I remember meeting Cuba’s former ambassador to Canada a few times, a guy who had been one of only two people from his law class in Havana who had stayed to support the revolution. Despite having that background, he was among those who indicated to me, clearly but discreetly, that some in the government favoured an opening up of Cuba’s political system but didn’t dare engage on the question in public for fear of reprisal. If Castro had opted to move in a democratic socialist direction, I think he would have found allies not only among many of the leaders in the Socialist International but also in countries like Canada.

Abele: We’ve been talking about the right-wing anti-communist ideology you saw at work throughout the region, but what about business interests? Don’t you think that a lot of what lay behind American foreign policy was simply the protection of capital?

Broadbent: Oh, undoubtedly — particularly in Latin America given the kinds of resources there and the American business interests who want to control them. But it’s still an open question as to how far the American state would have gone in that regard if different people had been in control. What if, for example, George McGovern had somehow won the ’72 presidential election instead of getting swamped? There was at one point a more liberal wing of American politicians who might have been less likely to react with the same violent hostility toward countries trying to nationalize their own resources. It could well be the case that the American state would still have gotten involved in protecting business interests even with different actors in power. But, quite apart from the pressures exerted by capitalist enterprises themselves, I think ideology played a significant role in shaping the aggressive U.S. policy toward Latin America in that era. I don’t think any capitalist forces were pushing Ronald Reagan: he was their willing handmaiden.

That potentially raises other complicated questions about the role of ideology in determining political outcomes as opposed to that of material self-interest or raw power. My own view, in relation to this and also much of what we’ve been discussing here, is that ideology is significant.

The Good Society

As I write, the great challenges that were revealed throughout the twentieth century have reappeared and threaten to further erode the social and economic rights that serve as the bedrock of freedom.

As global inequality remains largely untouched by Western governments, its social consequences are becoming more violent. In our market-dominated society, severe inequality has increasingly come to be accepted as ineluctable and even necessary — and the resulting discontent is compounded by a sense that decision-makers are unable or unwilling to do anything about it.

Whether we look at Canada or abroad, the various sources of insecurity are similar: the rising cost of living for ordinary people and extreme concentration of wealth at the top; the breakneck pace of technological change and damage to the global environment on an industrial scale; racist attacks on the principle of multicultural pluralism and the related demonization of immigration as the source of societal ills.

In countries as radically different as the United States and Sweden, elements of the dominant white population — spurred by far-right politicians and media — have come to see themselves as threatened by “minorities.” Racism and nativism have consequently become a strong current in the politics of the U.S., UK, France, Poland, Brazil, India, and Hungary, among others. In Canada, the convoy of trucks that descended on and remained in Ottawa included people belonging to radical rightwing movements committed to violence. It also included many people simply fed up with what they perceived as the condescending arrogance of the government led by Justin Trudeau — one out of touch with their day-to-day struggles. Pierre Poilievre, the newly elected leader of the Conservative Party, explicitly endorsed the convoy and has played footsie with white nationalists. It is difficult to know how durable the rise of this largely white right-wing extremism will be in Canada, where official multiculturalism and the plain need to expand the labour force through immigration have historically moderated these impulses. But there are worrying signs — particularly given the power of social media to spread lies and hatred across borders — that this is a growing movement with the goal of securing political power.

The political right is gaining momentum by seizing upon the insecurity felt among many Canadians. They have fertile ground: citizens today feel their world undergoing destabilizing changes that they have neither created nor been able to situate themselves within. The great exception to this trend, at home and abroad, is the top 5 percent of the population. As in the 1920s, their wealth continues to grow and their lifestyle of conspicuous consumption is radically different from that of their fellow citizens. As was the case in the decade before my birth, many in this elite see their location as the simple result of innate talent and initiative rather than as a consequence of the sweeping economic changes that have accompanied the neoliberal model of capitalism.

The global pandemic laid bare the gaps in both our social supports and our social fabric and demonstrated yet again that the health and well-being of the individual is fundamentally connected to the health and well-being of all. Crucial innovations of the welfare state, alongside important public health measures, are giving way to fiscal restraint. Canada’s health care system, care for the elderly, and its wider commitment to social and economic rights have been successively undermined by a starvation of resources and continued expansion of for-profit models and services.

Further, despite some progress in the relationship over the last generation, Indigenous peoples continue to fight the stubborn denial of their rights by Canadian governments. Recognized in Section 35 of the constitution, and enshrined in the UN Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples, these rights must now be implemented without equivocation. Some hard choices lie ahead, as questions of institutional reform and Indigenous land rights must be resolved. These obligations intersect with the many consequences of the global climate crisis, which is driving the search for rare earth minerals on Indigenous lands and accelerating the destruction caused by fire, storms, droughts, and floods in Canada and abroad.

So, what is to be done? Are we going to sit back and watch conservative politicians capitalize on economic insecurity to erode the potential of the social democratic state and reimpose their new, hollow model of “freedom”? They see starving the state as the solution to our problems. Take away the power and money of the state, they claim, and humanity will be set free. I reject this blinkered vision. Generations of Canadians, notably after the Second World War, demonstrated that the opposite is the case. It was the establishment of social rights like health care, unemployment insurance, and national pensions that enabled millions of Canadians to feel free for the first time in their lives. Having been undermined by successive governments, the remarkable achievements of the democratic age are now at risk of full-blown collapse. Now more than ever, we require prompt and effective state action to respond to the new destabilizing threats to people’s livelihoods and preserve a sustainable life on this planet.

A key theme of this book has been that ordinary people themselves — through social movements, unions, political parties, and civil society — wield the tools to make our institutions more just and our collective life more abundant. By working within the social circumstances of their lives, ordinary people have always been able to find concrete answers to their problems. I see important flickers of this countermovement today: workers organizing unions in sectors dominated by multinational behemoths like Amazon and Starbucks; child care advocates in Canada seeing five decades of struggle culminate in the creation of an affordable, universal national childcare program; climate activists on both sides of the border campaigning for a green industrial strategy.

There is no magic guidebook to consult, and there are no perfect solutions. Each generation must find answers to the challenges they face, although we may all learn from the past. In the wake of the Great Depression and two world wars, it became clear to people across the globe that the best instrument for countering the immense forces of global capitalism and achieving freedom was the social democratic state. In following their example, however, a new generation of Canadians will be able to achieve not the perfect society but the good society. Taking inspiration from the best of the social democratic tradition, I believe great things can still be done.

To be humane, societies must be democratic — and, to be democratic, every person must be afforded the economic and social rights necessary for their individual flourishing. On their own, political and civil freedoms are insufficient in the realization of that goal. I believed in 1968, and I believe today, that political democracy is not enough. In the twenty-first century, the rebuilding of social democracy must be our task. Social democracy alone offers the foundation upon which the lives of people everywhere can be made dignified, just, and exciting.

It is perhaps the appropriate moment to end this story with a reference to Willy Brandt. He, after all, illustrates the possibility of individual impact in history. His life, from fighting Nazism to bringing greater equality to West Germany and abroad, was one of political struggle. Like Brandt, activists today can overcome the impact of the right-wing forces of our time. We can build an alternative democratic agenda, creating more equality and decommodifying more of our lives. We don’t need perfection as a goal. We require simply compassion and thoughtful engagement. There is no guarantee that social democracy will triumph. But it is by far our best alternative, very much worth our political energy.

Order your copy of Seeking Social Democracy: Seven Decades in the Fight for Equality today at seekingsocialdemocracy.ca