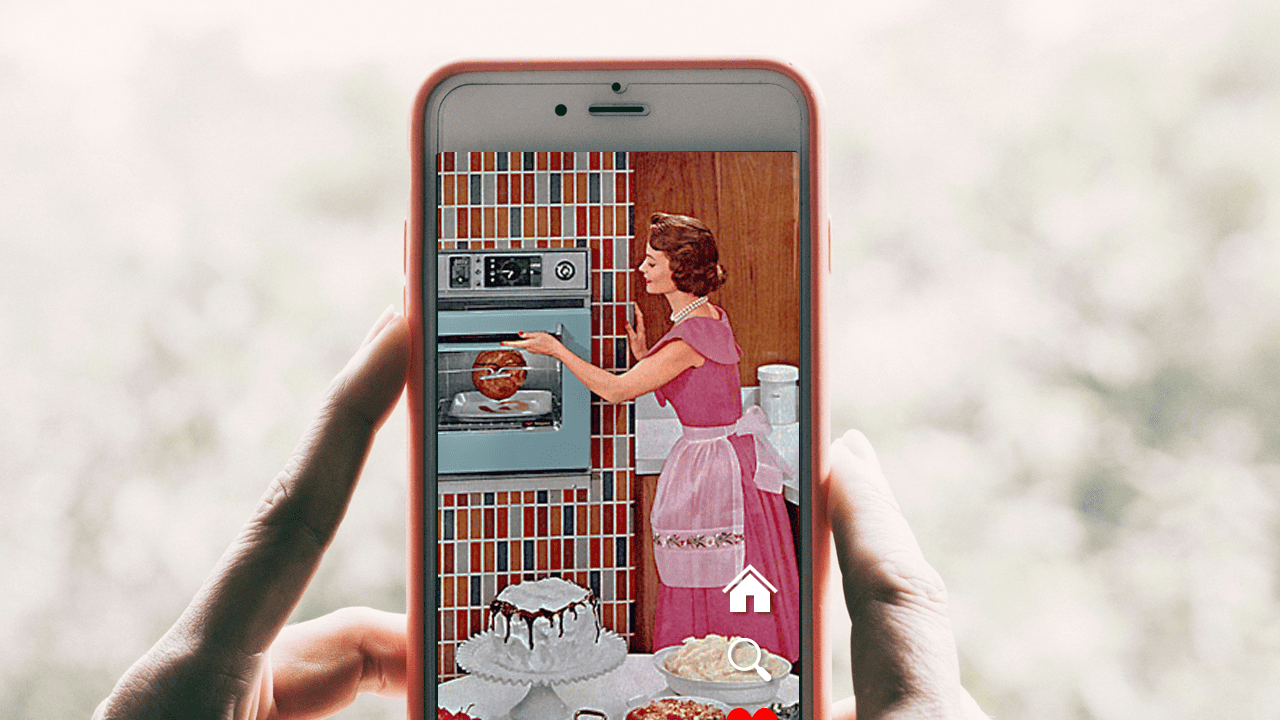

With softly curled blonde hair, fresh makeup, and a light blue floral dress, a 20-something woman dances to a trending song on TikTok while grinning widely. Her caption reads, “POV: You support traditional gender roles and believe your place is in the home.” Scrolling through her page, her content varies from homemade recipe tutorials, to homemaking tips, to makeup demonstrations, all interspersed with short videos espousing the value of women obeying their husbands and leaving the workforce to serve as stay at home wives and mothers. She self-identifies, repeatedly, as a trad-wife (1).

This content creator reflects a small, but highly vocal, subset of women who self-identify as so-called “traditional wives,” or “trad-wives” as is known in online social media shorthand. Trad-wives and their gendered counterpart “hustle-bros” are contemporary subcultural phenomena symptomatic of a reactionary rejection of the outcomes of late-stage capitalism, with values and practice expressed, and received, on social media platforms. While nominally eschewing the volatility found with expanding economic inequality, these individuals form identities conforming to traditional gendered roles in the economy within certain reactionary subcultures, but do not seek the transformation of the fundamental systemic problem.

Distinct from stay-at-home moms, the trad-wife online subculture takes domesticity to the extremes; pasta is made from scratch, clothing is often hand-washed, as are dishes, and the aesthetics of homemaking are highly prioritised, mostly removing the mechanical technologies that minimised women’s labour from these household tasks by the late 20th century. Beyond these extreme acts of domesticity, however, trad-wives also often speak out about relationships based on traditional gender roles, in which women are fundamentally subservient to men, and in which they strive to uphold rigid beauty standards and a rigorous performance of femininity. While they may exercise their autonomy in choosing to stay home, they also assume a high degree of economic and personal precarity due to a relationship in which their ‘value’ to their partner is tied to both their ability to perform household labour, and their ability to align with values of youth, beauty, and femininity.

It must also be noted that these women often choose to self-align themselves with right-wing narratives, occasionally with undercurrents of white supremacy (2). In short, trad-wives exist as a contemporary replication of an idealised, 1950’s-era Western housewife. More often than not, this existence is one that is highly documented via carefully edited photos and video content shared on social media. Trad-wives exist, in many ways, as a performance when contemporary economic and social realities would nominally dispute these values and practices (3).

Disconcertingly, women that participate in the trad-wife subculture often seem to echo troubling right-wing rhetoric, calling to a stark social regression of an era where women lacked financial independence and meaningful engagement in their relationships. Yet, trad-wives aren’t victims of legislative or systemic barriers; rather, they actively pursue ‘traditional’ lifestyles, eschewing formal labour structures. Instead of viewing trad-wives solely as disempowered figures reflecting growing right-wing values, they can also be seen as individuals with agency responding to economic inequality, stagnant wages, and disempowering work culture. They reject the 9 to 5 workday grind, retail jobs, and pension worries, seeking refuge in traditional gender roles and embracing the risk of full financial reliance on men over the perceived risks of participating in a collapsing economic system. In their own, albeit questionable, way trad-wives effectively reject the outcomes of late-stage capitalism.

Unpaid labour, though often overlooked, is still labour—whether it’s cooking from scratch, handwashing linens, sewing clothes, or raising children without daycare (4). However, trad-wives dictate their domestic labour on their terms; they choose to make meals with eggs laid by their own chickens; they choose to knit their sweaters and mend their socks. This autonomy contrasts sharply with that of formal workplaces. Ultimately, the lifestyle enjoyed by trad-wives is one of relative economic privilege. Ironically, the actors propagating the values and practice of this subculture also participate in some of the carved out economic activities of late-stage capitalism. That they often pursue secondary incomes provided by their social media content creation should also be noted, as potential evidence that even for the most ‘traditional minded’ among us, a single-income household may not be viable under contemporary economic conditions.

In effect, trad-wives embrace a gendered lifestyle to defy today’s formal work conditions and material disparities, but instead of engaging in critical movements for systemic change, they reinforce and participate in the hierarchies of capitalism. Rather than nostalgically reverting to the 1950’s, they leverage economic privilege, and sacrifice personal autonomy, to perform this escape of exploitative labour models on social media.

If trad-wives embody one form of gendered escapism from the workforce, the “hustle bros” exist as a contemporary corollary subculture in a parallel gendered dimension. Hustle-bros, a term that reflects a male-identified individual who, when facing the low wages of many traditional jobs, has instead sought out a multitude of side-hustles through which to create additional streams of income (5), also espouse traditional gender roles. Through their various entrepreneurial exploits, they aim to create a lifestyle centered around hyper-masculinity, one that attracts women seeking men who are able to financially sustain potential partners (6).

Hustle-bros exist as an extreme, and gendered, manifestation of “hustle culture” (7). In hustle culture’s underlying rhetoric, to be an individual reliant solely on traditional employment as a form of income is to be a failure. Instead, one should strive to pursue the so-called ‘grindset,’ creating venture after venture that creates additional income. Hustle culture posits that labour is impactful only when pursued through individualistic means, that income earned by working excessive hours on side-hustles is inherently more valuable than income earned in a traditional 9-5 job. Such income, to a hustle-bro, is particularly valuable when it exists in such an excess so as to attract women. Like trad-wives, hustle-bros also evangelize their subculture’s practices and values through social media content creation.

The sheer existence of individuals who feel the need to create upwards of ten different businesses in order to feel a sense of financial stability should be viewed as a highly-visible and ardent personification of the ways in which contemporary capitalism is failing modern workers. While rejecting the employment and income precarity of declining market society, instead of working with social movements seeking to transform society, participants in this subculture have double-downed on reinforcing fundamental ideals of capitalism. Similarly, the conception that one’s value as a partner stems only from one’s ability to create financial stability should be viewed as a profound rejection of current economic structures. While valorized on social media through leisure class participation alongside the so-called “grind”, the unsustainability of “hustle-culture” and the risk-taking of multiple ventures, especially for those participants not endowed with wealth, lends to cyclical exploitation among working-class men that buy-in to the subculture.

As hustle-bros and trad-wives are extreme symptomatic responses to contemporary workforce shortcomings, the growth and social media virality of these subcultures underscore the critical need for systemic overhaul. If left to fester, they could become new avenues for far-right nihilism and ideological expansion. This demands a thoughtful exploration of effective solutions to remedy the profound systemic deficiencies these roles represent. Initiatives like universal basic income, funded by higher taxation on top earners, could mark a crucial starting point for reform. Likewise, policies advocating for living wages would ensure fair compensation and dignified existence within the workforce, rejecting the notion of working excessively long hours, or sacrificing full personhood, just to make ends meet, are another crucial step. Instead of regressive, right-wing rhetoric that marginalizes individuals, it’s policies prioritising human dignity and tackling material inequalities that will drive substantive change. Until such reforms take root, late-stage capitalism will continue to drive gendered escapism, compelling self-exploitation over systemic change.

(1) Nicole Froio, “’Trad wives’ are using social media to romanticize a return to ‘traditional values’ as more and more women face post-COVID work/life balance burnout,” Business Insider, Nov 7, 2022. https://www.businessinsider.com/tiktoks-trad-wives-are-pushing-a-conservative-agenda-for-women-2022-11.

(2) Sian Norris, “Frilly dresses and white supremacy: welcome to the weird, frightening world of ‘trad wives,’” The Guardian, May 31, 2023.

(3) Vanessa Scaringi, “The False Escapism of Soft Girls and Tradwives,” TIME, Feb 28, 2024. https://time.com/6835737/soft-girls-tradwives-mental-health-essay/.

(4) Bela Kellogg, “The Tradwife Trilogy part 3: The real women behind the tradwife movement,” Michigan Daily, Jan 17, 2024. https://www.michigandaily.com/arts/digital-culture/the-tradwife-trilogy-part-3-the-real-women-behind-the-tradwife-movement/.

(5) Rebecca Jennings, “What YouTube hustle gurus are really selling you,” Vox, Mar 15, 2023. https://www.vox.com/culture/23640192/sebastian-ghiorghiu-youtube-hustle-gurus-passive-income-dropshipping.

(6) Günseli Yalcinkaya, “Rise and grind: how ‘sigma males’ are upturning the internet,” Dazed, Jan 13, 2022. https://www.dazeddigital.com/science-tech/article/55208/1/rise-and-grind-how-sigma-male-memes-are-upturning-the-man-o-sphere.

(7) Megan Carnegie, “Hustle culture: Is this the end of rise-and-grind?,” BBC, Apr 20, 2023. https://www.bbc.com/worklife/article/20230417-hustle-culture-is-this-the-end-of-rise-and-grind.