This article is part one of a four-part series providing a political history, overview and critical evaluation of the social democratic tradition in Western politics, with some reference to the Canadian experience. This series is a re-publication of the 2017 Discussion Paper entitled ‘Reflections on the Social Democratic Tradition‘ by Andrew Jackson, Broadbent Institute Senior Policy Advisor. Read Part two: Social Democracy from the Gilded Age to the Golden Age, Part three: Social Democracy from the Golden Age to the Great Recession, and Part four: Contemporary Prospects for Social Democracy.

Social democracy can be understood as both a social and political movement, and as a set of animating political principles and ideas. Both have historical antecedents in struggles for democracy, social and economic justice, greater equality and human rights for the poor and oppressed dating back at least to classical times. Most great religious traditions have espoused fundamental moral values of individual human dignity and equality, which have been embraced, developed and made more politically urgent by the social democratic tradition.

However, one has to start somewhere and social democracy is perhaps best understood as a reaction and proposed alternative to the liberal capitalist order that had become ascendant in the major industrialized countries of Europe and North America by the mid- to late-nineteenth century. To add to the complexity, social democracy, like all political movements and traditions, has been shaped in a major way by very different national contexts. Here we confine ourselves to Western Europe and North America, the heartland of nineteenth and twentieth century social democracy.

As argued by Karl Polanyi in his major book, The Great Transformation (1944), the rise of liberal capitalism involved a fundamental rupture with the past by destroying social rights to well-being based on custom and tradition such as existed in feudal times. Capitalism aimed not just to create a market economy but also a market society and it transformed labour into a commodity bought and sold on the market.

For the working class, those who did not own the means of production, be it land or industrial capital, survival came to depend upon being employed for a wage. But Polanyi stressed that labour (like nature) is a “fictitious commodity” in that labour is an inherently human activity carried out by individuals who resist exploitation and control of their capacities by others. He argued that turning labour (and nature) into commodities would lead to social destruction and this necessarily prompted a counter-movement to place a social, human and environmental framework around the liberal capitalist economy.

This was first seen in the rise of the labour movement that sought to raise wages above mere subsistence levels, to promote security of employment and to improve conditions at work, thus de-commodifying labour to a degree. The social counter-movement also sought to reduce or abolish exclusive reliance on the labour market and a wage for well-being by establishing rights to welfare outside the market, such as the right to unemployment relief and income support in old age, as well as rights to services such as education and health care.

In a similar vein, sociologist T.H. Marshall (1950) famously described the shift in the concept of citizenship in the liberal capitalist era. The birth of a liberal economic order was associated with the rise and protection of individual property rights and the rule of law, which were basic institutional prerequisites for a capitalist economy. The liberal era was also, gradually and contingently, characterized by the rise and protection of claims for civil rights such as liberty of the person, freedom of speech, freedom of assembly, and equality under the law.

Gradually and contingently, the movement for civil rights both enabled and pressed the case for democratic political rights, including the accountability of governments to elected legislatures, the right to vote and free elections. Capitalism was liberal but not democratic in its origins, and indeed in much of Europe, capitalism was not even especially liberal but coexisted with remnants of feudal and aristocratic dominance well into the twentieth century. For example, before the First World War, German ministers were still appointed by the Kaiser and the power of the elected Reichstag was confined to approval of budgets.

Lastly, Marshall noted the shift from democratic political citizenship to social citizenship as the workings of political democracy led to increasingly successful claims for collective social and economic rights. He described social citizenship, as “the right to share in full the social heritage and to live the life of a civilized being according to the standards prevailing in the society.’’ Like Polanyi’s socially embedded economy, social citizenship meant the recognition of labour rights, rights to social welfare and the right to services such as education and health care outside of the market as laid out in seminal international human rights documents such as the 1948 Universal Declaration of Human Rights.

A key political driver of such demands was the labour and social democratic movement for whom formal liberal freedoms to accumulate private property and to equality under the law were not very meaningful given stark inequalities of opportunity and condition based upon social class. The democratic franchise inevitably brought forward demands for positive social and economic rights to ameliorate deep inequalities of wealth, income and opportunity.

It is worth adding that while social democrats have argued for expanding social and economic rights, they have also recognized the critical importance of civil and political rights and have been among their strongest defenders. In Canada, socialist and social democratic political parties led the struggle for the expansion of the democratic franchise to non-property owners and were among the strongest supporters of modern human rights laws outlawing discrimination based upon gender, race and sexual orientation. To cite one key example, in 1947 the Co-operative Commonwealth (CCF) government in Saskatchewan passed Canada’s first Human Rights Act guaranteeing basic political and civil rights and prohibiting discrimination on the basis of race and religion. New Democratic Party of Canada (NDP) and its provincial wings have often taken unpopular positions on basic human rights issues, as for example in opposing the War Measures Act in 1970.

Drawing on thinkers such as Polanyi and Marshall, one can view social democracy as a key intellectual and political driver of the gradual transformation of liberal capitalism into what might be termed democratic capitalism wherein the market economy is partly de-commodified, where wage labour coexists with and is tempered by full employment, regulation of business in the public interest and effective recognition of a wide range of social and economic rights, including labour rights. Socialists of all stripes played a key role in this transition.

This was not, however, an exclusively social democratic political project, and the gradual rise of social citizenship was associated with other political traditions. In Britain, for example, progressive liberals from John Stuart Mill in the nineteenth century to John Maynard Keynes in the early twentieth century, along with kindred spirits such as US President Franklin Delano Roosevelt and New Deal liberals of the Democratic Party in the United States during the inter-war period, saw recognition of social rights as key to advancing individual liberties by establishing a basic floor of rights for all, as opposed to both radical liberal individualism and radical egalitarianism. In his 1944 State of the Union Message to Congress, Roosevelt called for a second bill of economic and social rights, arguing that “political rights alone are inadequate to assure us equality in the search for happiness” and that “true individual freedom cannot exist without economic security and independence.”

Progressive or social liberals also saw social protection and access to public services (plus greater regulation of capital in the public interest) as a means of legitimizing and preserving capitalist institutions, the market and private ownership, rather than as a stepping stone to socialism. Political liberals have at various times supported social democratic reform, whether it be through expanding parts of the welfare state such as public pensions and Medicare, or supporting progressive taxation in order to pay for public services and other social goods. However, as historian Tony Judt has remarked in Ill Fares the Land (2010), “whereas many liberals might see such taxation or public provision as a necessary evil, a social democratic vision of the good society entails from the outset a greater role for the state and the public sector.”

Today, some business leaders have seen social reforms as quite functional for capitalism. Traditional conservatives, especially confessional parties in Europe, also advanced labour rights and rights to welfare while maintaining a belief in the traditional family and social hierarchy. Indeed, Count Otto von Bismarck, a fiercely anti-socialist reactionary, introduced social insurance to provide pensions and health care as chancellor of Germany in the 1880s.

That said, as emphasized by Gøsta Esping-Andersen in his book The Three Worlds of Welfare Capitalism (1990), the social democratic welfare state differs from the liberal and social conservative welfare state in explicitly seeking widespread de-commodification. As constructed over the twentieth century, and as enacted in Scandinavia to the greatest extent, it stressed broad or universal social entitlements such as pensions based on citizenship as opposed to means-tested, relatively bare-bones programs for the non-affluent. It also called for provision of a wide range of public services, such as child care, education at all levels, social housing and elder care, delivered largely outside of the market.

These measures marked a distinct divergence from market and for-profit provision of social services combined with subsidies to support access to inferior public services for the non-affluent. The aim of the social democratic welfare state has been economic and social security, a civilized life for all, and a radical equalization of conditions and life-chances, not just a reduction in poverty as in the much more residual liberal welfare state. The socialization of many caring services led to the emergence of a large non-market sector of the economy and job market in the more social democratic countries, which also allowed women to participate more equally in the labour market.

Social democrats have been prepared to spend much more of society’s resources than even progressive liberals on income support programs and public services, financed from a steeply progressive income tax system, and have consciously sought to redistribute income and resources from the more to the less affluent much more significantly than liberal and conservative supporters of basic welfare rights. Social democrats have also much more consciously sought to carve out a non-market sphere that frees citizens from dependence upon the labour market and thus enhances the bargaining power of labour compared to employers.

Social democrats have a close historical link to the labour movement and have seen strong unions representing the great majority of workers as a major force for wage equality and for workplace and economic democracy that complements the progressive welfare state. While accepting the continued existence of a labour market, social democrats (above all in Scandinavia) have stressed the importance of full employment and collective bargaining rights combined with active labour market and training policies to effectively guarantee labour market opportunities for all and secure employment in a changing economy.

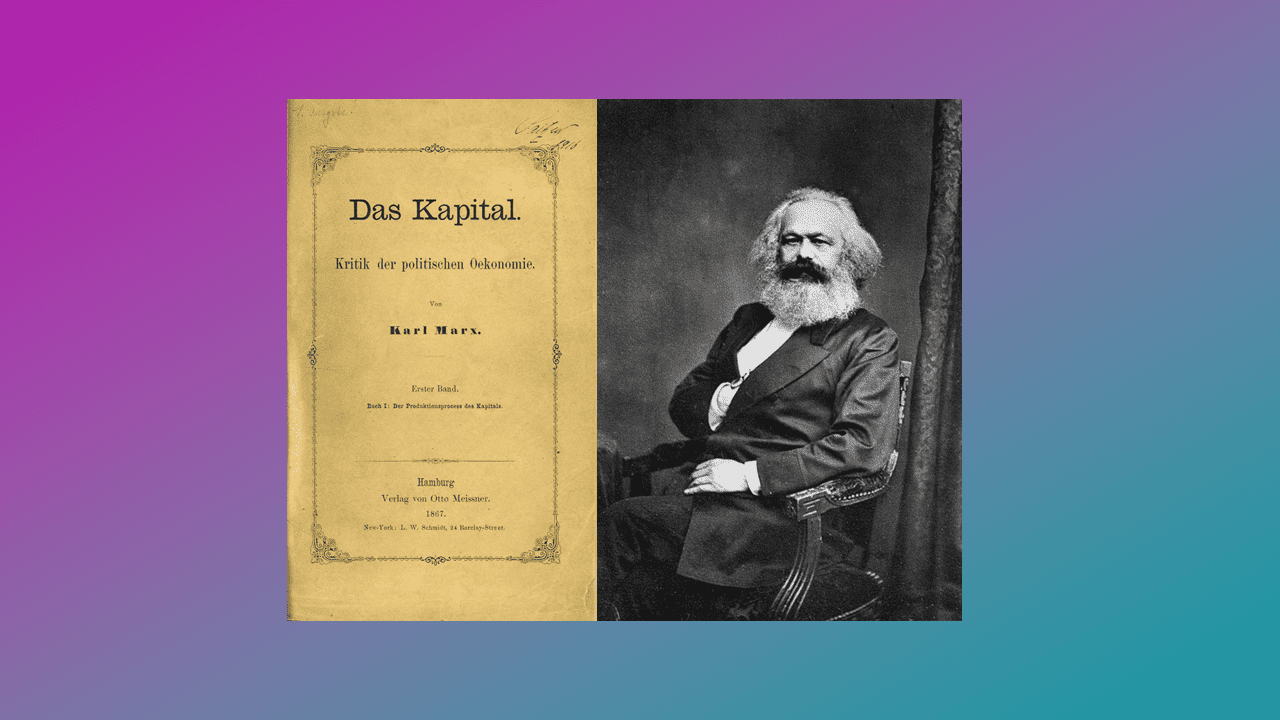

The idea of social democracy as a socially embedded market economy is relatively recent and can be partly contrasted to socialist traditions dating back at least as far back as Karl Marx that have insisted that capitalism must be replaced by a different form of economy, based predominantly on social ownership of the means of production. It was only gradually that many social democrats rejected socialism in this sense of moving beyond capitalism as a mode of production and as a social order. For Marxists (or at least those in the classical tradition synthesized by Friedrich Engels), there are fundamental tensions or contradictions between a capitalist economy and social citizenship (as Marshall himself acknowledged).

Marx can be, and has been, read in many ways. One strand, set out in Capital (1867), tended to the view that capitalism was not only inherently exploitative and a source of economic and social inequality due to highly concentrated ownership of wealth, but also doomed to fail as an economic system. The Communist Manifesto (1848) lauded the massive economic progress that capitalism had set in motion, but argued that such progress was inherently limited by capitalist relations of production. Marxists have seen a tendency to economic crisis due to wide swings in levels of business investment, financial speculation and inadequate effective demand rooted in the tendency for real wages and working-class consumption to lag behind productivity and the growth of productive capacity.

Since the birth of Marxism in the mid-nineteenth century, capitalism has been marked by periods of growth and periods of acute crisis, and by advances and retreats of labour and progressive political forces. Few contemporary socialists or social democracts would deny that capitalism in the sense of predominantly private ownership and control of the means of production can and has existed in quite different political and social institutional forms: from the minimalist night watchman state of the Victorian age studied by Marx and favoured by extreme liberals such as Ludwig von Mises and Friedrich Hayek, to Fascism, to the Keynesian welfare state of the post-war era, to the advanced social democracy of Sweden.

Many democratic socialists have argued and would still argue today that the continued concentrated ownership of the means of production is at the root of fundamental economic and social inequalities, and that social advances are tenuous so long as class power based upon private ownership of the commanding heights of the economy continues to exist. They note that the norm in a capitalist economy, notwithstanding government regulation, is for key economic decisions – how and where to invest – to be based on the logic of capital accumulation and competitive markets as opposed to production geared to meet human needs. While Marshall sees an extension of citizenship to the social sphere, Ellen Meiksins Wood argues that there has been a contraction of the political sphere under liberal capitalism insofar as the economy is largely left to its own devices to govern production and distribution, and is profoundly

shaped by the logic of capital accumulation and market competition.

Capitalists are necessarily driven to produce for profit rather than to produce to meet collective needs. For example, the private market economy drives production of luxury homes for the rich rather than high-standard, affordable housing for those in need. And employers who are prepared or compelled to pay decent wages and offer good working conditions may find that they are unable to compete in the market with companies that are ruthlessly exploitative. Countries with strong unions and highly developed welfare states may find it hard to attract mobile capital in a global economy where other countries offer low wages in relation to productivity and low taxes. Left to its own devices, capitalism will generate high levels of inequality of wealth since profits are mainly appropriated by a small minority who own large amounts of capital.

The destructive logic of capitalism can be countered through the redistributive welfare state, but redistribution and social regulation of the market may end up squeezing profits and thus undermining economic growth. A key dilemma facing social democrats in power has been that acceptance of the mixed economy necessarily entails maintaining “business confidence” in order to obtain the private investment that is needed to secure economic growth and thus the revenues needed to sustain social expenditures and public services. This problem receded from view in the Golden Age of post-war capitalism marked by both strong growth and falling inequality, but resurfaced in the stagflation crisis of the 1970s and has become more acute in the current era of fiercely competitive global capitalism.

In a long tradition that owes as much to the social teaching of the Catholic and other religious traditions as to Marxism, capitalism can also be criticized for its cultivation of commercial and acquisitive values and rampant materialism, what has been termed possessive individualism, as opposed to fostering the full and free development of each individual. Capitalism also underpins alienation at work, inherent in the drive for profit as opposed to the development of human capacities. Marxists such as C.B. Macpherson (1977) have argued that the liberal democratic welfare state is still a system of class rule that is inimical not just to sustained shared prosperity, but also to the full and equal development of human capacities. The continued power of capital in the economy and in the workplace necessarily also conveys political power, which stands in conflict with the goal of a more fully democratic society.

As will be argued in the next parts in this series, social democracy was, until the rise of neoliberalism in the 1970s and 1980s, not only about the welfare state and public services and expanding social rights, but also about regulated capitalism and economic democracy, or even about the ultimate transcendence of capitalism as an economic system. It was only during and after a long period of economic growth and stability, the so-called Golden Age of the 1950s and 1960s, that social democrats in the majority fully embraced the liberal so-called free market. But it turned out that the neoliberals who came to politically dominate in most of the advanced economies from the 1980s rejected full employment, regulated labour markets and much of the welfare state, and failed to deliver a successful alternative model for high employment, greater equality and economic stability.

Social democrats defended past social gains for the most part, but have largely failed to develop a fully convincing contemporary alternative to the social and economic policies of the right.