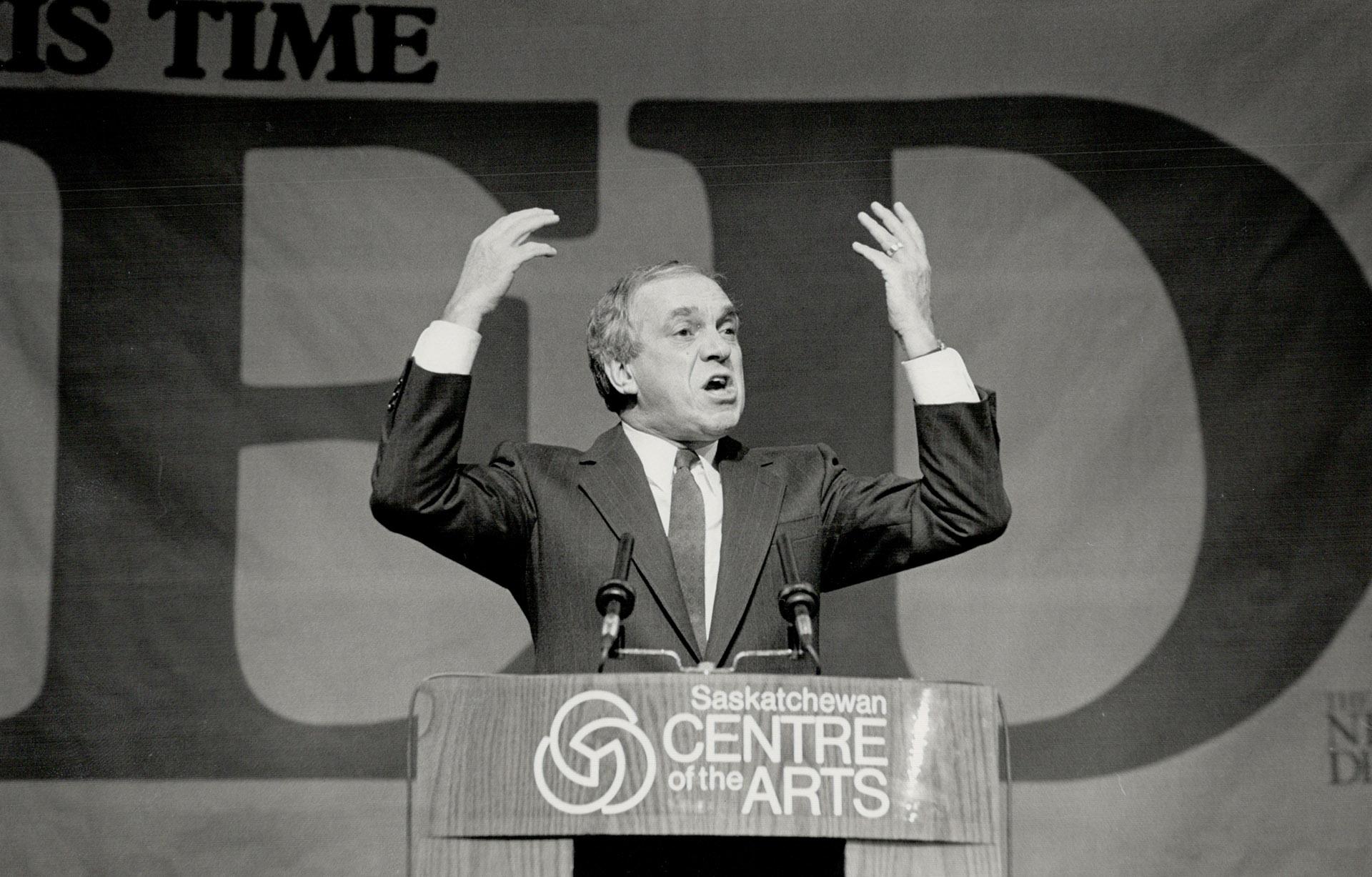

“The working stiff doesn’t get as much attention as before, or respect, and if any party works overtime to win their vote, it’s the Conservatives,” John Ibbitson wrote in the Globe and Mail on January 11th, 2024. “They would never have won that vote on Ed Broadbent’s watch.” Broadbent, who passed away at the age of 87 on the day Ibbitson’s article was published, had been elected leader of the New Democratic Party of Canada amid the first great crisis of post-war social democracy in the 1970s. The origins of that crisis, as he understood it, ran deep in the contention between capitalism and democracy: slower economic growth, rising oil prices, demographic change as populations aged, and a shifting industrial landscape that produced new employment patterns. The combination of these social and economic pressures precipitated a fiscal crisis that was seized upon by those who sought to subordinate society to the dictates of the market.

The parallels to the present are obvious and, again, the challenge for anyone aspiring to lead today’s federal NDP is familiar: providing an alternative vision to an economic model that has had disastrous consequences for the working-class. The decades since the rise of the neoliberal economic paradigm have bred stagnation and instability, concentrated power and weakened democracy, wreaked havoc on the natural world, fostered inequality and precarity, prioritized the short-term extraction of rents over long-term investments in productivity, and pulled ever more aspects of social life, from housing to education to healthcare, into the brutal logics of commodification and profit.

Since Broadbent’s passing, the 2025 federal election has pushed the NDP into crisis. In just under a decade, the party has fallen from the high of Official Opposition to the undeniable low of losing official party status in the House of Commons. With a mere seven seats and 6.29% of the vote, its performance was nothing short of disastrous. For all who are invested in restoring social democracy as a viable political project in Canada since the turn of the new millennium, the task ahead is considerable.

A more comprehensive picture of the NDP’s poor performance will emerge in time, particularly with the release of the 2025 Canadian Election Study by the Consortium on Electoral Democracy in early 2026. The NDP plans to release its own post-mortem analysis of the campaign later this year. Still, some clear conclusions can already be drawn as this was undoubtedly a unique election. Canada was swept up in an anti-incumbency trend that afflicted Western countries since the COVID-19 economic shock. Prime Minister Justin Trudeau had become deeply unpopular by the third year of the 44th Parliament, and his resignation had a decisive impact on party vote intentions.

From Trudeau’s resignation in early January 2025 to the start of the election writ period in late March, a significant share of NDP supporters shifted to the Liberal Party due to Trump’s annexation threats and declaration of global trade war, Carney’s appeal as a relatively unknown entity, and a desire to keep the Conservatives under Pierre Poilievre out of power. The widespread sense amongst potential supporters that the NDP could not win became a self-fulfilling prophecy. The party has long suffered at the hands of strategic voting, and in 2025 the calculus was particularly brutal.

Such a story, however, is too simplistic, both because it charitably ignores the NDP’s own failings and because it myopically fails to place the party’s performance in an appropriate international context where social democratic parties, in their right-ward shifts over several decades, have faced electoral disasters in recent years. One can criticize the major strategic decisions made by the party in the run-up to its catastrophic performance in April, above all the wisdom of its supply and confidence deal or whether it was advantageous to stick with federal NDP leader Jagmeet Singh as his popularity declined. These criticisms are easy in hindsight. However, most damningly the NDP scored poorly with voters during the 2025 election in its ability to handle the economy, affordability, and housing, which were issues of most concern for voters. According to campaign polling, even the party’s own supporters had little faith in its ability to fix the economy and fight inflation.

Western Trends in Social Democracy

The NDP is not alone in struggling to reach voters and even consolidate its base. Pasokification, or the decline of institutional centre-left political parties in Western countries through the 2010s as first demonstrated by the fall of PASOK, the Greek social democratic party, has been evident across the wealthy world for more than a decade. Social democratic parties struggle today for the working-class voter bases that they have historically relied on for support due to the abandonment of their traditional economic commitments. Structural transformations—above all technological change, globalization, the climate crisis, and shifting demographics—have created distributional questions that are difficult to answer even if a firm commitment to justice and equality are maintained, fragmenting the social democratic project. And the Western left lacks a consistent view of distributive justice, an issue that has been compounded in the 21st century as the traditional tension between labourist and egalitarian visions now contends with reparative claims and concerns that span generations.

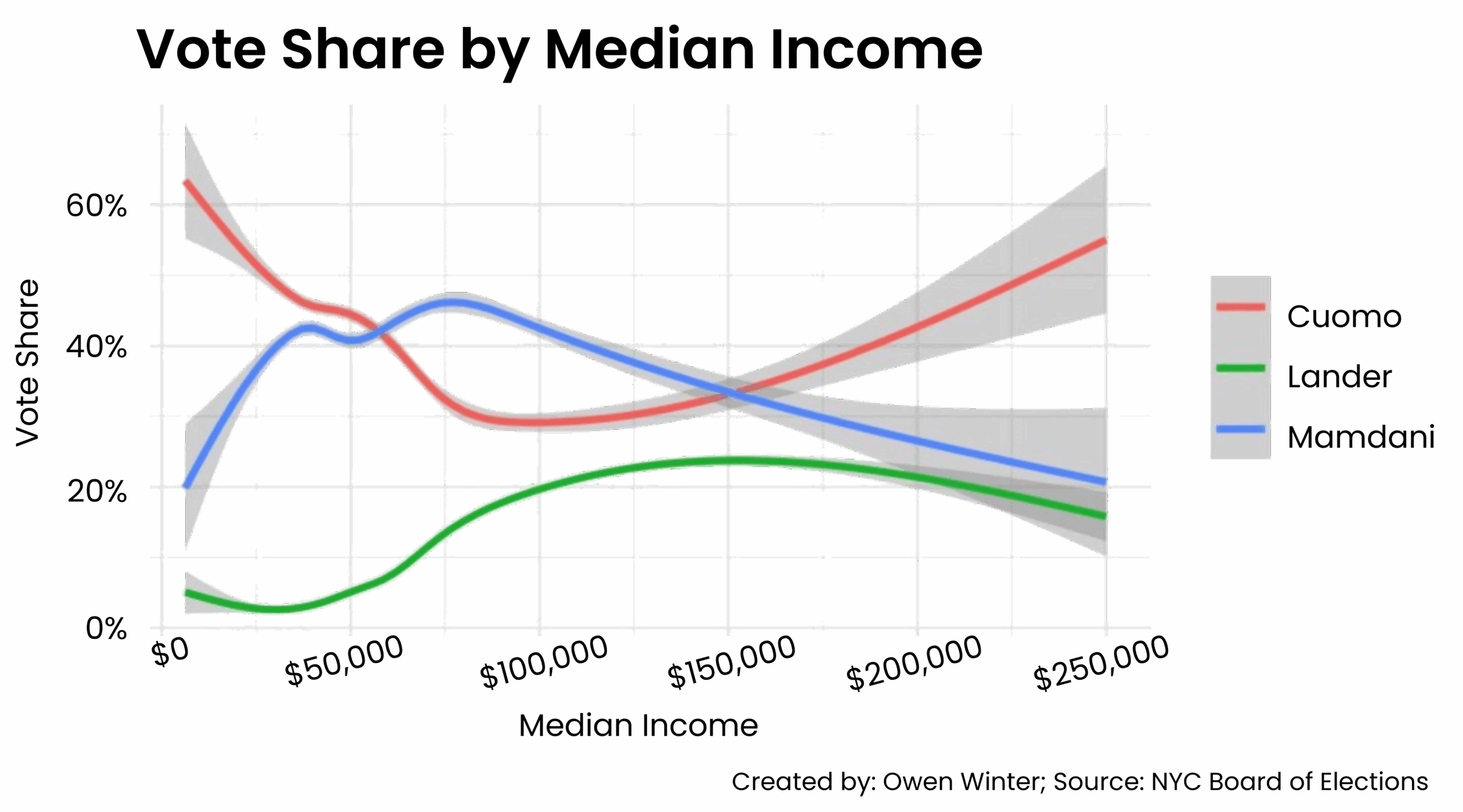

The support base of social democracy is now neither uniform nor predictable, a reality that recent electoral experiences demonstrate. The German federal election in early 2025 solidified the status of the Social Democratic Party as a party of pensioners, rather than workers. It is now in third place in the polls, having been overtaken by the far-right Alternative for Germany party who are within striking distance of a plurality. In the United Kingdom, the Labour Party returned to power in 2024 with the support of a cross-class coalition that masked significant divisions around age, education levels, ethic identity, and home ownership. Labour was decimated in local elections by spring 2025 and has fallen behind Reform UK in the polls, an insurgent right-wing populist party that has built on the success of the Brexit campaign. Zohran Mamdani, one of the most popular figures in the Western left of the moment, owed his improbable victory in the New York City Democratic Party mayoral primary in June largely to the support of middle-income voters; the lowest-income Democrats in New York City voted overwhelmingly for establishment figure Andrew Cuomo.

What would Ed Broadbent think?

Broadbent’s thinking has much to offer the overdue effort to return working-class politics to the heart of the NDP. He had a deep appreciation for the trade union movement, holding it chiefly responsible for the significant gains made by workers towards “self-respect and independence.” He was particularly influenced by John Kenneth Galbraith’s notion of countervailing power, the idea that private economic power is constrained by forces that emerge through the same processes that limit competition, something that furthers the self-regulation of economic life. The potential value of unions in response to the global inflationary crisis should not be underestimated: higher prices demand higher wages, specifically through a settlement that links productivity growth to wage increases for workers.

This is the site of traditional working-class struggle, but Broadbent recognized that more was needed, and knew that democracy must extend from political to economic life. This extension would include workers gaining control over the economic power traditionally held by management. For him, the traditional liberal view of democracy was not enough, but must be joined with a focus on equal access to opportunities for self-realization and a more complete control over all aspects of life. This is something, he believed, that a social democratic party should vigorously support.

Worker empowerment, however, means more than just management. Broadbent’s abiding interest in John Stuart Mill deserves more serious consideration in any contemporary project of the left. In particular, Mill’s own political commitments and his relationship to socialism are being extensively re-evaluated. A politics based on Mill is one that can appeal to socialists and liberals alike, placing individual liberty at its heart and remaining acutely aware of the risks of excessive state power. Attention should be paid to Mill’s view of socialism through worker experimentation and the coexistence of different business models. Significant opportunities exist to expand workers’ ownership in the economy, and any party that aspires to represent the interests of the working class would do well to seize them. These visionary proposals are in line with the ideas of the 19th century English philosopher that Broadbent embraced, and that the NDP should turn its attention to as well.

Broadbent was firm in his belief that all of this means little if it is not attached to a viable political project. “Politicians must lead,” he wrote in a 1998 academic article reflecting on the threat to economic and social rights of the prevailing neoliberal order. “It was politicians, responding to the post-war pressure of working people who created the welfare state. They led where their electorates in an unfocused way wanted to go. They must lead once again.” A post-2025 election poll, conducted by the Angus Reid Institute, found that 53% of Canadians would consider voting for the NDP in the future, pointing to a potential electoral ceiling that greatly exceeds its historic performance. Liberal voters and younger Canadians were particularly open to supporting the NDP, pointing to a potentially brighter future if the party is able to seize it. 45% of all respondents made their willingness to consider supporting the party conditional on its future direction and leader. There is much work to do.

The working-class has long been animated by the pursuit of greater opportunity and dignity, of ever more freedom in the face of whatever stands against it, and of a life of well-deserved material comfort. Social democrats must always be on their side.

Here, Broadbent is again helpful. He believed in “the importance of explicit ideological talk” that must involve laying out “a social philosophy that is more comprehensive.” This needs to “recognise competition and private economic gain as being essential and legitimate if we are to produce efficiently beyond the level of scarcity”, while at the same time articulating “with equal conviction our public needs and duties, our profoundly human disposition to cooperate with others, our need for social and economic rights.”

At the heart of the social democratic creed is the belief that the economy should serve society and not the other way around, and that people should be protected from its vagaries and empowered to thrive within it however they see fit. Markets are capable of remarkable things and are made by governments; it is always possible to remake their rules. It speaks to the choices of other regimes and political projects that markets are often designed to limit competition to concentrate power at the top, and that markets have moral, economic, and social limits that must be defined and enforced with vigilance. The working-class has long been animated by the pursuit of greater opportunity and dignity, of ever more freedom in the face of whatever stands against it, and of a life of well-deserved material comfort. Social democrats must always be on their side.

A social democratic party cannot win an election in Canada in the 21st century through the support of the working-class alone, but it cannot keep its soul without it. The task of the NDP is to find ways to add to, rather than supplant, its traditional working-class base, and to do so it must cut through the Gordian Knot of competing distributional claims that arise in post-industrial democratic society. Social democracy is built on the foundational insight that the employment relationship is fundamentally unjust, and is concerned, at its core, with whether you have the things that you need to secure your basic livelihood. It is not difficult to extrapolate this into a broader understanding of the power divides that shape our society.

The NDP, with the right direction, has the capacity to become the party of people left behind by neoliberal capitalism in Canada. That, on its own, is not enough. Canadians are turning away with anger towards right-wing political projects without practical solutions. The NDP can, and must, give them something better. The NDP, if it is to have any chance of electoral success, needs to show that it can be the party of the future with a progressive vision that remains grounded in its roots while not trying to restore the past. Electoral politics, as it was reminded in the 2025 election, can be unforgiving if a party does not change to meet the moment and present a vision for tomorrow. Ed Broadbent had one. The next leader of the federal NDP must be able to build one too.