This October 2023 federal NDP convention saw delegates gather in Hamilton, in the context of a minority parliament sure to dissolve into a general election in the not-too-distant future. The first in-person convention since 2018 seemed to bookend five years of political deadlock, despite the energy that initially accompanied Jagmeet Singh’s arrival as leader. Showing great personal dedication, Singh worked hard to recreate this energy in a variety of ways in front of the 2023 party membership.

Singh and the top officials at NDP headquarters in Ottawa seem sincerely committed to what they believe to be the best playbook for success at the polls. In general elections that elevate party leaders above all else, Canadians need to “get to know Jagmeet.” The leader has a compelling personal story, and the more he tells it, the more the public will come to identify with him.

But, is the leader-centric approach the best way to go?

The original model for socialist parties in Western Europe was what political scientist Maurice Duverger called the ‘mass party.’ The mass party was a distinct social phenomenon from the existing ‘elite’ or ‘cadre’ parties. Whereas the old parties simply grew out of the personal and class networks of largely pre-democratic parliamentary caucuses, the mass party was a democratic movement through which the working-class organized itself. Its distinct advantage was its capacity to mobilize and empower the great mass of the population.

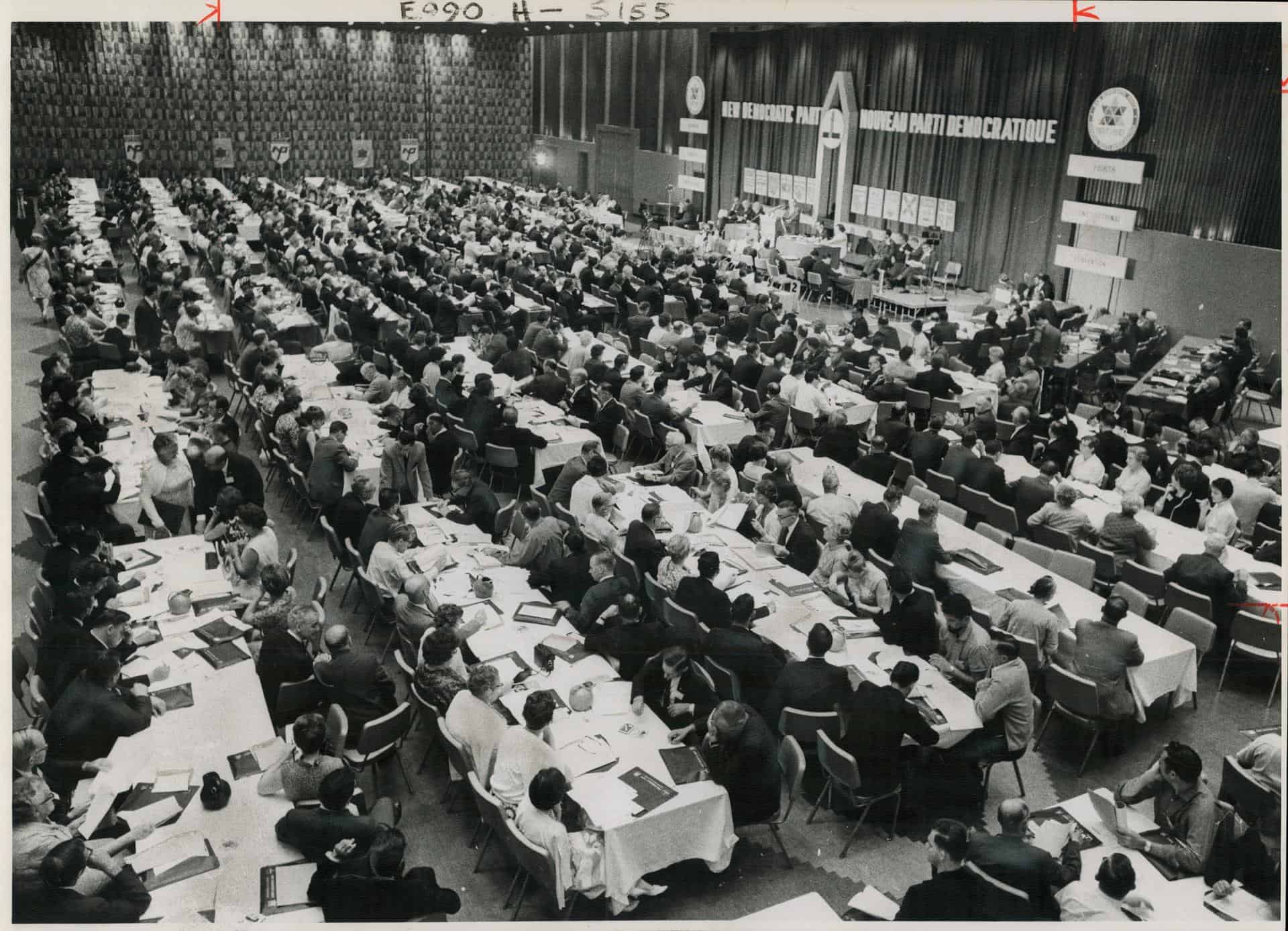

In the Co-operative Commonwealth Federation (CCF) and sections of the early NDP, an adaptation of the mass party idea clearly motivated the core of the membership, and was reflected in the party’s internal structures, even if the party never achieved the level of strength and organization of its British and European counterparts.

Since the mid-20th century, factors like changes in mass media, social media, and parties’ programmatic convergence on economic matters have altered the way people relate to politics. In Europe, the mass party model has declined. In Canada, a more elitist model has always been dominant. NDP sections have increasingly sought to imitate their competitors’ sophisticated ‘political marketing’ techniques, prioritizing a consumeristic ‘electoral market’ over the old-fashioned idea of a membership base. These developments have mirrored other trends in civil society, including the decline of unions and voluntary associations generally. Perhaps it is unreasonable to expect political parties to be an exception to these trends, at least in the Global North.

On the other hand, people still desire a source of community and purpose. As Becky Bond and Zack Exley argued in their 2016 book Rules for Revolutionaries, when the stakes are high enough to make a difference, people will surprise you by how much work they are willing to take on. However, the big ideas have to be there to inspire them. Bond and Exley point to the efficacy of decentralized, volunteer-driven “big organizing” models in some recent US Democratic Party campaigns.

What if the CCF-NDP’s history as a mass party and a democratic, membership-based movement for a better world is in fact its unique strength in Canadian politics?

In spite of its strategic choices over the years, the NDP still sometimes benefits from the perception that it is an entity somehow unlike Canada’s traditional governing parties. For the time being, neither provincial nor federal sections have broken conclusively with their history as longstanding electoral vehicles of the democratic left. To the extent that younger generations of activists are attracted to the NDP, I believe that it is primarily because they have some level of awareness of the party as—in the words of historian Desmond Morton— “a Canadian institution.” What if New Democrats embraced this side of their history?

Members of Canada’s large and diverse working class might be eager to participate in a membership-based movement for social, economic, and environmental justice—if only it would put itself out there in these terms. When NDP messaging both federally and provincially focuses so heavily on the caucus and the leader, it is hard to blame the public for presuming that this is simply another political party like the others—a clique of notables competing for power and prestige.

Membership in a political party could become attractive, and indeed meaningful, if it felt empowering. In turn, the party itself could derive its own benefits from becoming more people-powered. There are many places where New Democrats might start, from improving riding association and campus club contact information, to maintaining policy principles for platform stability between elections, to the old school practice of high-level manifestos that call ordinary Canadians to action.

With a stronger membership culture, bodies like federal and provincial councils, executives, and equity commissions would develop stronger legitimacy and policy capacity. The NDP’s federal council was involved in platform development as late as the 1990s. There should also be significant space for the Broadbent Institute and the Douglas-Coldwell-Layton Foundation to support an intellectual reinvestment in the party’s democratic intermediary bodies. Engaging party members with these civil society networks could certainly support the work of caucus and make party membership valuable, adding accountability for both membership and their political representatives.

A shift back toward mass party characteristics would probably be unintuitive to some in the today’s different NDP sections. The longstanding weakness of membership culture since at least the 2000s also raises issues around legitimacy and capacity affecting all of the party’s governance bodies outside the House of Commons. It is possible that the prevailing staff-driven and caucus-driven model is now irreversibly entrenched. But it is also possible to imagine rebuilding the NDP’s membership culture. Though challenging, this may be a necessary process for the long-term viability of an institution built on the foundations of the mass party.

Andrew Jackson has recently invited New Democrats to take “the fire, not the ashes” from the past, paraphrasing a quote attributed to French socialist leader Jean Jaurès. The embers of the mass party are still smouldering.