There is a notion that Canada was late to the ‘mass party’ formation of labour or social democratic parties in the late 19th and early 20th centuries that rose primarily across Europe, as well as independent Latin America and among colonial entities across industrializing Asia. In Canada, the Co-Operative Commonwealth Federation was founded in 1932 as an adaptation of the mass party before its predecessor, the present-day New Democratic Party, was established in 1961. In Europe, the mass party played a hegemonic role in the lives of the working-classes during the height of the European age of imperialism, providing them with a sense of community, education, a basic social safety net, and a political voice within the metropole. Starting with the Social Democratic Party of Germany, in its present form established in 1875, the mass party formation quickly spread across continental Europe.[1] The mass party structure played a vital role in establishing trust between labour parties and the working-classes they represented in parliaments, giving them a political base of support. It was through the buildup of working-class power that these early mass parties could enact transformative change that improved societies within the confines of this turn-of-the-century period.

A century later, as social democratic parties capitulated to the neoliberal period in the 1990s and early 2000s, these mass party infrastructures were destroyed in favour of ‘professionalization’ wherein political parties become more centralized and professionalized, relying less on ideologically driven volunteers, and more so on consultants, strategic communications, and campaign spending.[2] Professionalization within social democratic parties around the world has weakened historical ties with labour unions and engagement with working-class communities, in favour of collaboration with financial classes and top-down elite party infrastructure. Since the 2008 Great Recession, there has been a crisis of confidence in the current economic system, and confidence in social democratic parties, that has lent to the rise of far-right political movements in Canada and across the West. To understand how left-wing parties previously built support among the working-classes, in defence of democracy against fascism, historical reference points may prove useful. For contemporary Canada, while a late bloomer in building a national mass social democratic party, earlier regional episodes could help to template a path forward.

In the late 19th century, fisherman of the Newfoundland colony, before becoming a Dominion in 1907 and a Canadian province in 1949, faced heavy exploitation under a ‘credit system’ in which merchants ‘loaned’ fishing equipment to workers in the spring, and expected to be paid in the fall with the profits from the fisheries.[3] The merchants would then set the prices for the fish in the fall, setting low purchasing prices from the fishermen, while increasing prices on the international market. This led to many fishermen to permanent indebtedness towards the merchants that generated a cycle of poverty, worsened by low-yield fishing seasons.

A 1933 Royal Commission would later describe Newfoundland fisherman as “living in conditions of abject poverty.”[4] Pre-Confederation fisherman would often live in unsanitary, overcrowded, damp outport homes scattered along the shores of Newfoundland. A striking survey once observed that Newfoundland children were significantly shorter and lighter than mainland Canadian children due to chronic hunger and lack of nutrition. Once they exhausted their catch of dried cod, families would subsist on diets almost entirely consisting of “flour, tea, and molasses.”[5] Scurvy, influenza, tuberculosis, and other diseases occurred often among these communities due to the dilapidated living conditions. There was little to no educational infrastructure in these communities, with children being forced into the workplace and left with no hope of social or economic advancement. Fishermen and their families were forced into lives of extreme alienation and destitution by a merchant class that was exploiting their labour with no existing political or economic structure willing to improve their material conditions. Late colonial-era and Dominion-era political parties, the various iterations of Newfoundland Liberal and Conservative Parties, and the Liberal splinter Newfoundland People’s Party, maintained the economic status quo in favour of the merchants.[6]

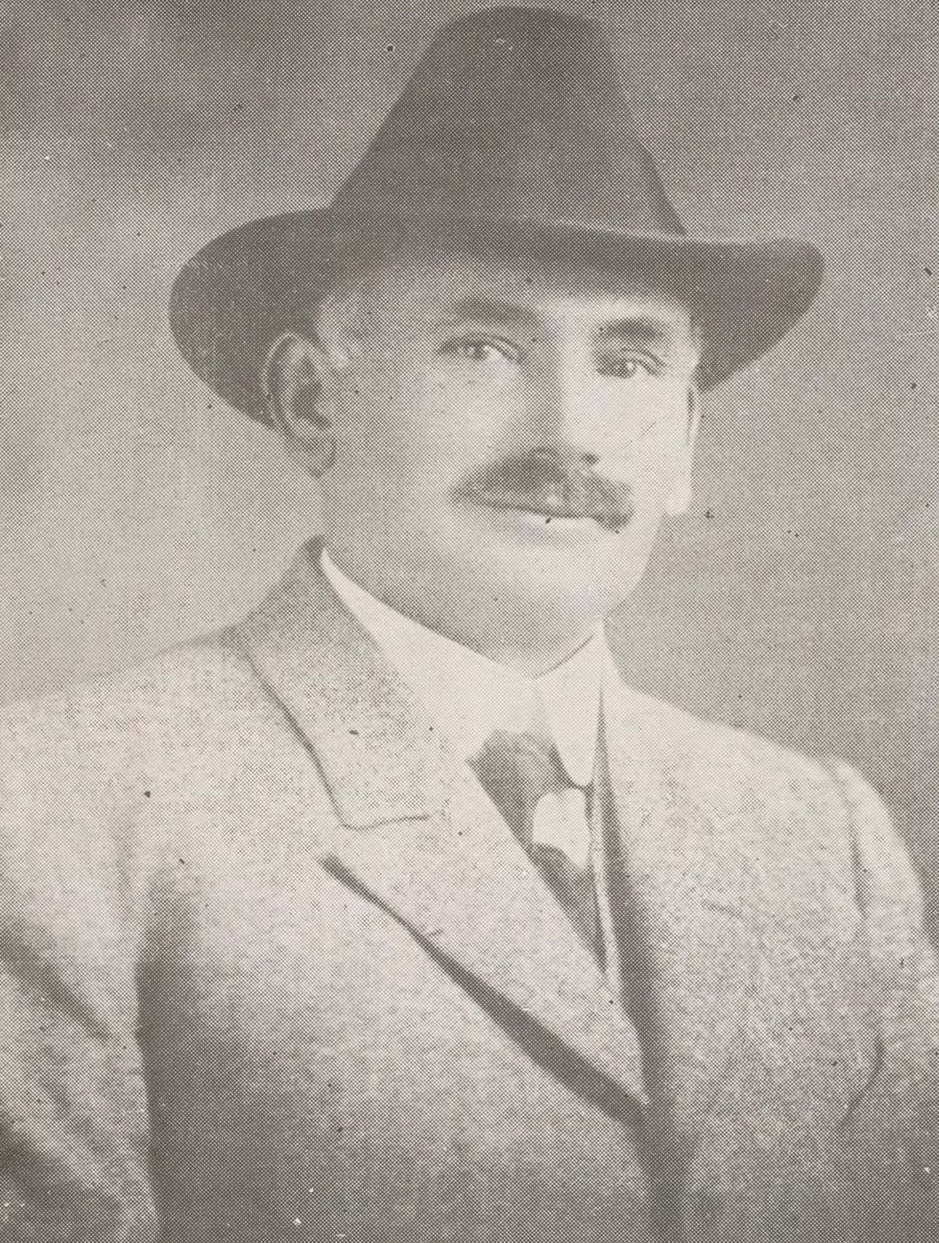

Decades before Newfoundland’s entry into Confederation, and before the creation of the CCF, Newfoundland fisherman attempted to turn the tides against exploitation through the development of a mass party structure and organization in November 1908, with the formation of the Fishermen’s Protective Union (FPU).[7] Founded as a cooperative movement, the workers’ organization took several approaches pushing back against the oppressive economic structure that favoured the merchants, from organizing workers, to the establishment of cooperative retail, to forming a new political party that elected members to the Newfoundland House of Assembly. The FPU was first led by labour organizer William Ford Coaker, who had led workers’ strikes demanding fair wages since he was a teenager.[8]

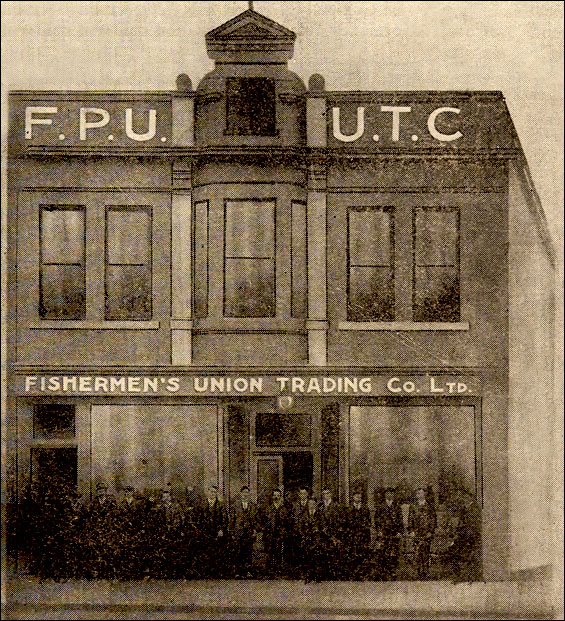

Setting the FPU apart from traditional labour unions and political parties, the workers’ organization established the Fishermen’s Union Trading Company (FUTC) to bulk purchase food and fishing equipment for its membership and sell catch directly to markets to circumvent the sales and profits of powerful merchants. The FUTC functioned as a retail cooperative, selling items at far lower prices to FPU members than merchants would set, and re-distributing the profits from retail sales towards the purchase of more goods and maintenance. By 1916, the organization grew to over 21,000 members (over half of all fishermen in Newfoundland), 206 FPU Councils, 4,421 worker-shareholders in the FUTC, and over 40 stores across the Dominion, from urban St. John’s to rural northwestern St. Anthony.[9] Becoming deeply rooted in their communities, the FPU provided alternative economic and governance structures that were run by and for the working-class. Other cooperatives would later form with similar organizational structures out of the FPU’s initiative, such as a company for rural electricity, a shipbuilding company, and a cold storage company to help workers preserve catch.[10] Perceived as a threat to Newfoundland’s merchant class, the FPU was attacked by their allies in the press who tried “red-scare” tactics, stoking fear of uneducated “rough” fishermen controlling the economic levers of the Dominion, and stoking sectarian conflict between Catholics and Protestants. As an alternative, the FPU established The Fishermen’s Advocate as their own newspaper, written for and by fishermen.

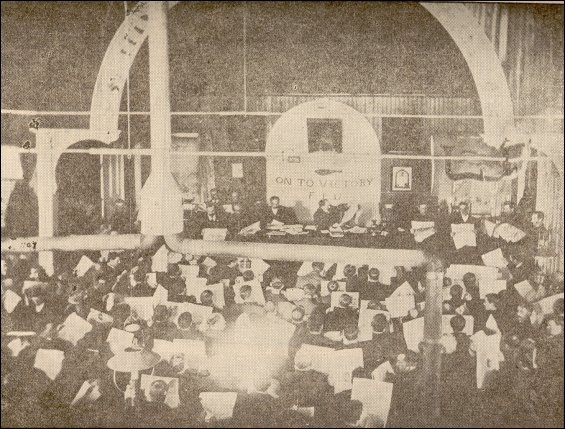

Newfoundland’s working-class were creating their own society, as an alternative to the merchant-class system that achieved greater inequality between themselves and the working fishermen. The transformative program of the FPU heightened economic power and instilled a community pride in towns across Newfoundland. Parades, song halls, and community events were held by the Local FPU Councils while towns would proudly display the iconic flag of the FPU, inspiring a sense of hope for a better future and way of life for Newfoundland’s working-class fishermen.

In the electoral arena, the FPU established the Union Party to implement worker-focused reform. The Union Party, led by Coaker, campaigned on the ‘Bonavista Platform,’ advocating government regulations of fish grading to ensure fair pricing, free and compulsory education, a minimum wage, old age pensions and more, and ran in the 1913 General Election where they won eight of the nine seats they contested in the 36 seat legislature. The Union Party lost its ninth seat by just ten votes and became the second largest party in the Newfoundland and Labrador House of Assembly. As a ‘mass party,’ Unionist candidates were chosen by the elected Local FPU Councils, increasing democratic participation for workers. As historian John Feltman described, “the people of northern districts of Newfoundland had won self-government for the first time…The Union members, with few exceptions, were members of the toiling class.”[11] This was a radical departure from other contemporary left-wing and labour parties around the world, with many of them headed by an intellectual ‘vanguard’ rather than workers themselves. This was also a stronger position for a workers’ party in 1913 than had previously been achieved anywhere else in the neighbouring Dominion of Canada.

When FPU Assembly Members took their seats, they did not wear formal clothing but instead wore the “rough clothing of the fishermen, as a matter of pride.” Shocking the social and economic elite of St. John’s, Sir Robert Bond, first Prime Minister of the Dominion of Newfoundland and Liberal Party leader, resigned his leadership after coming in third to the FPU’s party that they formed a coalition with, in the aftermath of the 1913 election. When Coaker first spoke in Parliament as the effective Leader of the Opposition to the People’s Party government, he proclaimed,

“A revolution, though a peaceful one, has been brought about in Newfoundland. The fisherman, the common man, the toiler of Newfoundland, has made up his mind that he is going to be represented in the floors of the House… the common man all over the world has made up his mind that the future is going to be a different thing than the past.”

The Union Party would force the government’s hand in passing worker reforms for the logging and sealing industries, implementing a minimum wage, and exposing corruption within the government.

The crisis of the First World War would split the FPU in the similar way labour unions and social democratic political parties across Europe and the Americas would contend with the issues of conscription and support for their respective nation’s war efforts. While initially opposing conscription at the outbreak of the war, the FPU eventually relented and joined a national coalition government with the two other parties in the General Assembly in 1917, with Coaker as the Minister of Fisheries.[12] The post-war election held in 1919 culminated in a coalition government between the Union Party (securing 11 seats and 30.8% of the vote) and the Liberal-Reform Party, with Coaker again serving as Minister of the Fisheries under Prime Minister Richard Squires. With the FPU empowered over the fisheries, the coalition government enacted reforms that modernized the fishery and forced fish exporters to cooperate in setting prices, rather than undercut each other. Exporters, however, in opposition to the FPU, found ways to circumvent the government’s new rules and further damaged the fishing economy.[13]

The economic downturn caused by the collapse of these regulations, alongside the effects of support for conscription, reduced support for Coaker and the Union Party. The market reforms would eventually produce their intended result of fair competition, but the political damage had already been done. Apart from these regulations, Newfoundland’s fishery industry saw decline by the 1920s, crashing prices and causing unemployment. While the Union Party-Liberal Reform coalition won re-election in 1923, the FPU decided to withdraw from electoral politics in the snap election in 1924. Though the Union would make a comeback and form a coalition government with the Liberals again in 1928, as Newfoundland’s public finances fell into disarray due to the Great Depression, responsible government was suspended and the unelected Commission of Government was introduced for the Dominion in 1934 until joining Confederation in 1949.

There are many lessons for today’s labour organizers and social democrats to learn from the FPU as a mass party, such as its deep entrenchment within struggling working-class communities, and the alternative economic and financial institutions it built. The FPU also organized workers outside of the traditional Fordist-industries, demonstrating how modern-day gig work can be organized through the provision of mutual aid and services. The FPU’s Union Party was also able to quickly thrive in electoral politics due to its connection with the Bonavista communities it focused its efforts on; present-day efforts to build mass parties must also build power similarly, by first organizing and building alternatively just and equitable institutions to bring working-class members into the fold. If social democrats want to succeed in Canada, they must build a party that workers see themselves in and view themselves as being a part of. Like the FPU’s Fisherman’s Advocate, building alternative working-class mass media can help to fight back against corporate, oligarchic control of information. If Canadians want to rebuild working-class power for this new era, it is vital to learn the organizing methods and systems that previously won the today’s rights and privileges that are now being stripped away.

Notes

[1] Richard M. Hunt, German Social Democracy: 1918–1933 (Chicago: Quadrangle Books, 1964), 15.

[2] Russell J. Dalton and Martin P. Wattenberg, “Unthinkable Democracy: Political Change in Advanced Industrial Democracies,” in Parties Without Partisans: Political Change in Advanced Industrial Democracies, ed. Russell J. Dalton and Martin P. Wattenberg (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2000).

[3] Christopher Willmore, “Newfoundland in International Context: 1758–1895” (University of Victoria, April 2020), 20–21.

[4] Great Britain, Newfoundland Royal Commission, Newfoundland Royal Commission 1933: Report (London: H.M. Stationery Office, 1933), 5.

[5] Keith Collier, “Malnutrition in Newfoundland and Labrador,” Heritage Newfoundland and Labrador (2011).

[6] John Feltham, “The Union in Politics,” in The Development of the FPU in Newfoundland, 1908–1923 (St. John’s: Memorial University, 1959).

[7] Robert Cuff, “Fishermen’s Protective Union,” in Encyclopedia of Newfoundland and Labrador, vol. II (St. John’s: Newfoundland Book Publishers, 1984).

[8] Catherine F. Horan, “Coaker, Sir William Ford,” in Encyclopedia of Newfoundland and Labrador, vol. I (St. John’s: Newfoundland Book Publishers, 1967).

[9] Robert Cuff, “Fishermen’s Protective Union,” in Encyclopedia of Newfoundland and Labrador, vol. II (St. John’s: Newfoundland Book Publishers, 1984).

[10] R. W. Guy, “Coaker and His Union,” Newfoundland Quarterly (1985).

[11] John Feltham, “The Union in Politics,” in The Development of the FPU in Newfoundland, 1908–1923 (St. John’s: Memorial University, 1959).

[12] Ibid.

[13] Ian McDonald, “The Reformer Coaker,” in The Book of Newfoundland, vol. VI (St. John’s: Newfoundland Book Publishers, 1967).